At the just concluded American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) conference, two sessions in the last two time slots were:

Integrating Cultural Change – Punctuated Equilibria Models in Near Eastern Archaeology and Egyptology I and II.

Neither session specifically mentioned the Hebrew Bible nor do I recall any questions from the audience addressing that topic either. Nonetheless, these sessions may provide more insight into the writing of the Hebrew Bible than sessions directly addressing that topic including at the Society of Biblical Literature (SBL) conference.

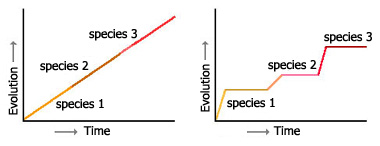

The term “punctuated equilibria” refers to when “long periods of stasis and apparently uneventful continuum are broken up by brief periods of rapid and profound changes. During such ‘punctures,’ the whole social –political system is exposed to a series of vital changes that influence essentially every component (subsystem) of the society, bringing it to a qualitatively new level of development and attained complexity and texture” (from the abstract of Mirolsav Bárta, the first presenter).

The genesis of the term arose in the field of evolution. Some scientists thought the more steady-state linear evolution approach proposed by Darwin did not fit the data. Instead, they developed a hypothesis that described a series of dramatic changes following a period of comparative stability. The changes “punctuated” the status quo. The most famous name associated with this hypothesis is Stephen Jay Gould. The most famous example of a punctuation probably is an asteroid hitting the earth leading to demise of the dinosaurs and the rise of the age of mammals.

The hypothesis is descriptive in nature and not explanatory. It is a way of organizing data but not explaining it. In the initial presentation by Bárta, he proposed that five such punctuations occurred during the Old Kingdom in Egypt. These leap periods led to the establishment of the first territorial state in human history, an elaborate bureaucratic apparatus, and massive stone-build monuments among other changes. During the Q&A, I asked about a causal factor for these five leaps. The model has no set trigger but simply states that such leaps periodically occur and are quick when they do.

Perhaps the most famous political example of such a change in the lifetime of many of the attendees at the sessions was the collapse of the Soviet Union. It is reasonable to say that during the 1980s, people did not anticipate such a collapse (excluding Ronald Reagan), that when it did occur it took people by surprise, and it happened very quickly. The Arab Spring may be considered a partially aborted punctuation.

In biblical times, a significant one occurred in 1177 BCE. That year also appears in the title of a book by Eric Cline, one of the presenters in the second session. He informed us that when he started to write the book, he envisioned the Sea Peoples as the causal agent for the collapse of the Late Bronze Age. The more he investigated the subject, the more he came to realize that a “perfect storm” involving multiple factors had led to its demise. In the end, what the Iron Curtain, the Arab despots, and the Late Bronze Age have in common is a certain fragility despite the image of great enduring strength and stability.

I first sought to apply the concept of punctuated equilibrium to the writing of the Hebrew Bible in a paper entitled “The Mesha Stele: Underutilized Key to Understanding Israelite History and the Writing of the Bible” presented at the ASOR conference in 2010. In my paper, I wrote and said:

Therefore I wish to propose the Punctuated Equilibrium Theory in contrast to the Big Bang Theory of Writing. This theory of writing is based on the premises that

1. We are a story-telling species

2. We tell stories through the available media about the issues that concern us

3. Ancient Israel was not a people of silence with no stories to tell, songs to sing, holidays to celebrate, or places to assemble.

In this context, I propose that in Iron II Israel a series of separate and independent alphabet prose narrative scrolls were written over the centuries primarily by the prophets as the political situation warranted. They served as the basis for the integrated narrative which would be created post-721 BCE in the kingdom of Judah.

In that paper, I did not explain how I derived the term “punctuated equilibrium” so it was quite likely that many in the audience were not familiar with it. I employed the term to refer to the aftermath of Mesha’s destruction of the Yahweh sanctuary at Mount Nebo, home of the traditional burial site of the founder of the Israelite people. In this sense, Mesha functioned as an asteroid disrupting the life of the Levites or prophets of Moses much as temple destructions would later do to temple priests. Although I did not use the word “trauma” at that time, I suggested that the trauma led to writing as a means of coping with the event. In this suggestion I was guided by the work of Anthony Campbell in 1986 in his book Of Prophets and Kings (1986) and later with the assistance of Mark O’Brien, Unfolding the Deuteronomistic History: Origins, Upgrades, and Present Text (2000). In the latter, they elaborated on his hypothesis by identifying verse by verse the texts that belonged to this prophetic narrative. Mesha’s actions meant to those who believed that the sanctuary dedicated to the burial place of the founder that the Omrides had lost their legitimacy to rule. In this regard both Jehu and Hazael could be understood as the rod of Yahweh’s anger, the staff of Yahweh’s fury, instruments of Yahweh delivering his message of wrath upon the underserving Omrides.

By coincidence, just prior to the ASOR conference, I read Self-Interest or Communal Interest: An Ideology of Leadership in the Gideon, Abimelech, and Jephthah Narratives by Eliyahu Assis (2005). His analysis included Judges 6:8-10:

Judges 6:8 the LORD sent a prophet to the people of Israel; and he said to them, “Thus says the LORD, the God of Israel: I led you up from Egypt, and brought you out of the house of bondage; 9 and I delivered you from the hand of the Egyptians, and from the hand of all who oppressed you, and drove them out before you, and gave you their land; 10 and I said to you, `I am the LORD your God; you shall not pay reverence to the gods of the Amorites, in whose land you dwell.’ But you have not given heed to my voice.”

He compared the words to the beginning of the covenant in Ex. 20:2-3:

Exodus 20:2 “I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. 3 “You shall have no other gods before me.

Suddenly when reading this book, it occurred to me that this exchange in the story of Gideon was about something going on with Egypt at the time it was written. Frequently biblical scholars observe that the story of the golden calves (Ex. 32) relates to the time of Jeroboam I. In that story, the people say that (i) Moses brought them out of the land of Egypt (Ex. 32:1), (ii) the golden calf Aaron had fashioned brought them out of the land of Egypt, and (iii) according to Moses, Yahweh brought them out of the land of Egypt (Ex. 32:11). Evidently there was a discussion and disagreement about exactly how the people left the land of Egypt. There was no disagreement about having left Egypt, just who should be considered responsible.

The time of Jeroboam also was the time of Sheshonq’s invasion of the land of Canaan. So instead of the biblical texts simply being a tirade between the Aaronid and Levite priesthoods, was there also a debate about the very identity of Israel and responsibility for its existence? How could Jeroboam be the new Moses if he was in cahoots with Pharaoh? Did Sheshonq’s invasion trigger a written response as the northern prophets (Ahijah) sought to cope with what it meant for Israelite identity based on having left the land of Egypt?

Consider the circumstances at the time of Sheshonq’s invasion which apparently brought him to Megiddo. It had been two hundred years since Ramses VI had left Megiddo ending Egyptian hegemony in the land after 350 years beginning with Thutmose III at Megiddo. It had been about 250 years since Ramses (Se-se-ra) III’s invasion in 1177 BCE also remembered in a song mentioning Megiddo. And it had been nearly 300 years since Merneptah had claimed to have destroyed the seed of Israel. Now Pharaoh was back campaigning in the land. For the northern prophets, this action was traumatic.

I do not claim to have the details worked out, but just as there was a prophet narrative following Mesha’s destruction of the sanctuary to Yahweh, so there might be a Sheshonq narrative in response to when he invaded the land.

As a result of these readings, musings, and sessions, I think it is reasonable to consider a punctuated equilibria approach to the writing of the Hebrew Bible. Israel wrote when it needed to in response to periodic traumas that punctuated their sense of identity. And they did so for centuries each time an “asteroid” fell.

Philistines/Creation the monarchy (10th century BCE)

Sheshonq (5th year of Rehoboam)

Mesha (around 843 BCE leading to Jehu’s deposing the Omrides)

Hazael (8th century BCE success of Jeroboam II against the Aramaeans).

Each of these threats engendered the composition of a separate scroll by the northern prophets to explain how the threat could have occurred and who was the savior (if any) who ended it. These scrolls were brought to Jerusalem and eventually combined into a single scroll that would include Judah as well. The “asteroids” for ancient Israel were the foreign kings who threated their existence and one response was an alphabet prose narrative that addressed the situation. The challenge now is to escape the Persian-fixation on the time at the end of this process and to identify the writings following each punctuation of the Israelite equilibrium.

Note: If on the Saturday overlap between the ASOR and SBL conferences I had attended the SBL conference instead of the ASOR conference as I sometimes do, this blog would not have been written.