Infrastructure is in the news again. It was in the news repeatedly during the previous administration. It seemed like every other week or month was dedicated to infrastructure. Alas, no such bill ever emerged yet alone to be proposed and voted on.

This administration is different. Not only has it had talked the talked, it is trying to walk the walk. That trying has been dragging on for months. The finish line seems both tantalizingly close and impossibly far. For some reason, Democrats, especially the Senator from West Virginia, think it is actually possible for a come-together bill to be crafted in a bipartisan spirit. In the meantime, in case the Democrats stop living in their alternate reality and decide to live in the real world, there are some legitimate infrastructure issues to deal with.

We are a story telling species. So consider these two stories that contrast Europe and the United States.

(www.vibe.com)

On the left is Jason Bourne. His stories are kinetic ones of perpetual movement on mass transit except for the scenes in New York. On the right, the “Fast and Furious” movie dynamo is all about fast and furious cars and people with no mass transit in sight.

1825-1969: CAN DO AMERICA

Once upon a time the United States of America was a can-do society. This was before NIMBY and “Don’t Do, Sue!” came to dominate the country. Many people may not remember there had been a time when America actually could build things.

1825 serves as a convenient start date of this brief overview. The wars with England were over. Instead of looking over our shoulder to see when the next threat would emerge we could face forward and look ahead. That meant to the west. The physical expression of that perception was the Erie Canal. Work on Clinton’s Folly began on July 4, 1817 (its bicentennial has passed) and ended on November 4, 1825 with the Wedding of the Waters in New York Harbor. The Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean were joined. New York was becoming the Empire State. New York City was surpassing Boston and Philadelphia (the sports rivalries have old roots). The Wedding bicentennial of Can-Do America is only four years away and will occur as the American Revolution 250th begins to rev up.

The Erie Canal was a technological marvel for its time. It is easy to overlook just how wide New York State is from Albany to Buffalo unless you drive it. It is easy to overlook the challenge in constructing the locks necessary for the canal to work. In historical terms, the Erie Canal was a game changer. It was cutting edge.

Personally, I like the fact that it was longest geological trench in the world. The 1820s was known as the Diluvial Decade. People debated the birth of the earth seeking to reconcile what would become geology with the biblical chronology proposed by Bishop Ussher. At that point in time no one knew about glacial movements so the only way to explain the presence of erratics was that the hand of God placed these rocks far removed from where they apparently belonged.

The movement west continued to bring about infrastructure developments.

Before there was the internet, there was the telegraph. Soon telegraph lines spanned the country.

Before rich people went up into space, railroad barons crisscrossed the land with rail lines, most famously the Transcontinental Railroad, the first but not the only such line.

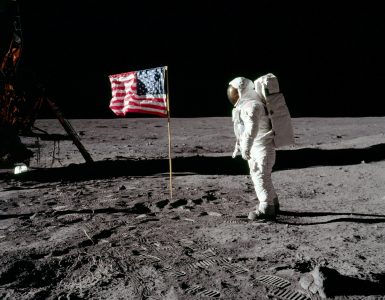

Since those railroads there have been other adventuresome achievements from the Brooklyn Bridge to the Interstate highway system to multiple major dams. Finally, the extended period of American success placed people on the moon, still a standard for human infrastructure achievement.

1969 to TODAY: DON’T DO, SUE

In recent decades there has been significant shift in infrastructure construction development in the United States. Once upon a time engineers and bold leadership dominated the process. Now the key people are the lawyers. Will they allow something to done? How long will it take to overcome the objections? How much will it cost? Why even bother?

Another factor of course is that anything new has to account for the existence something old already built. Roads, railroads, bridges, canals, dams, subways, airports, all have to contend with existing versions of themselves. Repairs are one thing, but the odds are anything new or innovative has to replace something physically there. In the meantime, urban areas have been developed in areas that once were vacant. A century ago, the original Yankee Stadium was in the middle of nowhere, empty land. Comparatively speaking, building it was simple. By contrast, the new Yankee Stadium had to be squeezed into a developed area.

New York provides case studies on the challenges facing infrastructure development. Individual items can be replaced/renovated but system changes are problematic.

The standalone Tappan Zee Bridge can and was replaced and improved. I still consider it a victory when I see signs for the Tappan Zee Bridge in its real name.

It will “soon” be possible for people from Long Island to take the train directly to Grand Central.

It may “soon” be possible for people from Westchester to take the train directly to Penn Station.

The Port Authority Bus Terminal may become a 21st century terminal.

Penn Station can and has been improved but not all of it. At this point who knows what is to come and when.

Think of the time and enormous overrun costs involved in any of these endeavors just to catch up in creating a 21st century mass transit system in what is supposed to be the financial center of the universe.

Don’t worry. I am not going to recount the saga of the elusive Hudson River Gateway tunnels that will fix the problems caused by Hurricane Sandy years ago and ameliorate the train logjam problem. Instead I want to highlight how limited our vision has become.

As our president said in an earlier lifetime, New York had a Third World airport. LaGuardia Airport, named after a 20th century mayor so not that old, had become an embarrassment. Rebuilding it to create a 21st century airport can and is being done. Progress definitely is being made. Driving and parking at the airport can be a nightmare now. I am drawing on ancient memories from the pre-COVID era. The airport definitely can be replaced but can it be expanded and connected to Manhattan by mass transit?

Consider these comments from an article on this topic from July 21 (NYT). When the concept of a connection originally was proposed by the Governor, the estimated cost was $450 million. Now it has nearly quintupled. The proposed route from the airport to Manhattan is not a direct one. The reason is the Port Authority chose a route that would be the least disruptive to the surrounding neighborhoods, a concern China does not have to deal with. Now imagine the challenge of upgrading the Amtrak line from Boston to Washington to create a high-speed line.

Now consider the headline from this article the following day (July 22, VICE):

Congrats to Andrew Cuomo on His Useless LaGuardia AirTrain

The only thing the future LaGuardia AirTrain will accomplish is reminding us why our transportation infrastructure rarely gets better. By Aaron Gordon

CORRIDOR PLAN MAY SHORTEN COMMUTE

This phrase was the front-page headline in my local paper on July 19. Note the definitive “May.” It is a far cry from JFK promising a man on the moon in this decade. The article identifies 150 projects costing $117 billion as part of Connect 35. Besides the project not being funded, many of the individual projects were for repair and not expanded service. “The corridor is lined with aging assets from Washington to Boston, bridges and tunnels dating back to the 1800s [THE CAN DO ERA] with track signal and power systems that are beyond their useful life,” said NJ Transit President and CEO Kevin Corbett, co-chair Northeast Corridor Commission.

One of the goals is to increase train speeds 160 miles ON SOME SEGMENTS of the corridor. This proposed speed in some segments pales before the over 200 MPH levels attained by high-speed trains in Europe and Asia right now. Connect 35 is a 15-year plan, meaning longer in practice, which is to “prepare for future high-speed travel.” So after at least 15 years if we are lucky, some portions of the #1 rail corridor in the United States will be 50 MPH slower than Europe and Asia at present. Our goal is in 15 years to be behind where the world is now so then we can then prepare to catch-up if we want to. If we do decide in 2036 or later that we do want to catch up, maybe somewhere around 2050 we will have a high-speed rail line comparable to what exists in Europe and Asia now…assuming the shoreline has not changed due to climate change. It is an open admission that we will never catch-up.