We are a storytelling species. That means history is important. The enrollments as history major majors may be in decline. The earning prospects for history majors may seem bleak. But the importance of history remains.

In one of his last acts as President, the outgoing President released his 1776 Commission report.

In one of his first acts as President, the incoming President disbanded that commission.

SHARING HISTORY

History is important. People know where they were when they learned about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. People know where they were when they learned that President John Kennedy had been assassinated. People know where they were when the learned the World Trade Towers had collapsed. Not only did people know where they were, they had similar reactions. These national events became part of the shared history for the generation that experienced them and the subsequent generations that remembered them.

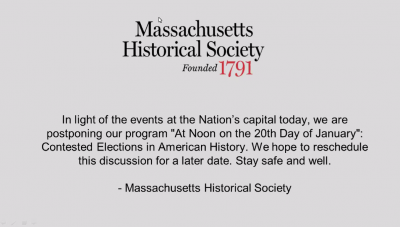

The situation is drastically different with civil war events. These events from America’s three civil wars produced divided responses. People knew where they were when they found out about Lexington and Concord but they did not share the same response. People knew where they were when they found out about Fort Sumter but they did not share the same response. People know where they were when they found out the events of January 6, but they do not share the same response or even the same set of facts:

Was it an attempted insurrection instigated by the worst President in the history of the United States, or

Was it an attempt by antifa to undermine the greatest President in the history of the United States?

HISTORY SCHOLARS

Historians debate who is the greatest and who is the worst President in American history. To the best of my knowledge, there has never been an instance where a single individual simultaneously was considered to be both the best and the worst presidents by approximately half the population for each. Perhaps the non-Presidential figure with a similar split in the American population is Robert E. Lee.

As a storytelling species, it is critical that we have shared stories to tell. Think of how much of family gatherings is dedicated to the telling of family stories that you have heard before as well as new ones. Think of how hard it is to have family gatherings today without and without Covid. In the current issue of Time, Charlotte Alter writes:

A democracy is only as strong as the faith of its participants. At the very least, that faith must be rooted in some sense of shared reality, a willingness to agree on to disagree according to the laws laid out in the Constitution.

She is correct but there is no shared reality now. The differences are not simply people having different favorites for the Superbowl or whether baseball or football or basketball is the national sport. There is no agreement now on even what the score is of a given game, whether the players are legitimate, or if a game is real, meaning not digitally created.

The last serious well-known effort to create a national narrative for the 21st century today was by Jill Lepore, These Truths: A History of the United States (2018). By coincidence, today I received my hard copy of The American Historical Review (125/5 December 2020). Her book is the subject of the roundtable for this issue with four scholars commenting on it. Once I have read it, I will report on their comments on the success and/or failure of her book (previously I wrote about a roundtable on “Native American and Indigenous Studies: Another Culture Wars Episode.”

By coincidence, on the same day that I received the journal, I watched an online lecture presented by the American Philosophical Society on the book Past and Prologue: Politics and Memory in the American Revolution by Michael D. Hattem. The main theme of the talk was the absence of an historical memory in the new nation. By that I mean, the former British colonists had a long historical memory through their being British, a memory that extended to the French and Indian War. The British colonists were proud to support their side against the French and the Indians allied against them. They were proud to express their loyalty to King George III. And then they weren’t.

Now the new country was faced with the task of creating a shared national history for a country that was younger than their children. Hatten spoke about the transformation that occurred as people cut themselves off from their shared British history to create a new shared American history.

Christopher Columbus was part of that effort to create a shared history. The people in the colonies from Pilgrims to Puritans to Dutch to Quakers to Cavaliers plus others had not come to America at one time and for the same reasons. By the time Georgia became a colony, Virginia had “celebrated” its centennial. In this sense, all American citizens had Columbus in common. If he hadn’t done what he did, none of them would have been here. As a result, he was part of creating a shared national history that went back before 1776 and wasn’t British. Americans could observe a Columbus tricentennial in 1792, name the capital after him, and use Columbia as a non-British national symbol (and college name).

Another shared history-based form of identity was as God’s New Israel. It wasn’t mentioned in the talk and I don’t know if it is in Hattem’s book or not. A connection with an event three millennia ago certainly was one way to develop a non-British history. This identification was not a new one post-1776 but it was an example of how the United States crafted an identity for itself.

Finally, homage should be paid to the one individual above all others who provided Americans with a shared identity. Without George Washington holding the country together, no one knows if there even would have been a united country to hold together. Perhaps there would have been two.

THE UNSHARED HISTORY

At present, there are three major incompatible views about the American Revolution, the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the creating of a shared national narrative. The three are:

1. Woke view: The New York Times 1619 – The documents are racist and the country is illegitimate based on white supremacy and social stratification. 1619 has been the subject of previous blogs but its story needs to be updated based on ongoing reactions to it.

2. Patriotic view: Hamilton, the Musical – A flawed but great start and an ongoing story as evidenced by the cast of the show. It also has been the subject of previous blogs.

3. Trumpican: 1776 Commission – They are divinely inspired documents especially through the Second Amendment.

Before turning to these three incompatible national narratives, I will start the challenge to craft a national narrative with the four, maybe five national myths that are regarded as historical by tens of millions of people. These myths are:

1. the myth of the empty land

2. the myth of stolen from Africa

3. the myth of no slavery in the North

4. the myth of the Lost Cause.

Now we have a new myth attempting to join these four longstanding ones:

5. the myth of the stolen election.

Whether or not this most recent myth has the power to be sustained cannot yet be determined. It is still being formed and is connected to the insurrection attempt instigated by the loser. The well-known saying that “I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters” now has been proven true. That saying may become part of the myth and detached from its January 23, 2016, date. In the myth it will be easy to conflate these two January events.

Obviously, I have my work cut out for me if I am to go through this process. We do need a shared national narrative for the 21st century. For me, at least, at this point in time, the steps outlined here are a way towards creating one even though it won’t even matter if I succeed.