Child sacrifice is in the news. Not in those words, of course. Rather it is the willingness of various governors and parents to risk the lives of children rather than to vaccinate them. Sometimes, people hide behind the Bible as a way of claiming a religious objection. Such protestations are intended to cover-up the real reason or reasons whatever they may be. Still, it is worth examining some biblical stories to see how the issue of child sacrifice was handled in ancient times.

ABRAHAM AND ISAAC

One of the most famous stories involving child sacrifice occurs in the story of Abraham and Isaac (Gen. 22). This story of the binding of the son or Akedah is read yearly as part of the Rosh Hashanah holiday meaning last week. It is a powerful and emotionally gut-wrenching story. It lives on in storytelling and art and packs a punch. In my opinion, the story originally was performed before a live audience so whoever played the role of Abraham may be considered one of the great ancient actors. It is a role to die for.

In the story, God commands Abraham to sacrifice his only son in a burnt offering. The purpose here is not to provide an exegesis of the story. Instead, I simply note its existence in the canonical text. Spoiler alert: just in the nick of time a ram is discovered entangled in the thicket and is sacrificed instead. Scholars debate whether or not in the original story the son was sacrificed, how old he was at that time, and if the change involved legitimating temple sacrifice in Jerusalem since the event occurred at the future location of the ram sacrifice. My perspective is that the original audience witnessing the story was meant to be revolted by the prospect of the child sacrifice.

DAVID AND ABSALOM

The situation is a little clearer in the story of David and Absalom. According to the text (II Sam. 18:5), David instructs his commanders to go gently with his son and not to kill him. A few verses later, Absalom like the ram in the Abraham story, becomes entangled as well. This time it is his long hair in a tree. Shortly afterwards Joab dispatches Absalom with nary a thought about the command he had been given from David. When messengers bring David the news, the king famously responds as one would have expected Abraham to have done if he had gone through with the child sacrifice: and as he went, he said, “O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! Would I had died instead of you, O Absalom, my son, my son!” (II Sam. 18:33)

How is this a sacrifice as opposed to an execution of an opponent who rebelled against his king? Joab, of course, is person who arranged for Uriah, husband of Bathsheba, to be on the frontlines so he could be killed. He knew what David really wanted then and he fulfilled his role. The same happened here. This is not to say that David did not have great remorse over the way events unfolded. However, as with Abraham, David was willing to have his son die for a greater cause. In this case obedience to God meant preservation of the kingdom of Yahweh with his son David as king.

SOLOMON AND THE BABY

In this also famous story, Solomon displays his wisdom in threatening to cleave a baby in two and then not having too (I Kings 3). The situation arises due to the death of a child and two women claiming to be the mother of a living child coincidentally born at the same time. Solomon devises this test of splitting the living baby in half and having each claimant receive a half. The ruse leads to the real mother expressing her willingness to sacrifice her child, that is, give the child up to the false mother, for the sake of keeping the child alive. The fact that the story occurs just before the kingdom itself splits into two with each side claiming to be the true kingdom of God is another factor. By contrast today, anti-vaxx mothers are quite willing to play Russian roulette with both their own child and the children of others.

MESHA AND SON

The final example to be included in this blog involves a child sacrifice by a non-Israelite. In this situation, Jehoram, and son of Ahab, the king of Israel is waging a war against Moab (II Kings 3). At first the battle is going well for the Israelite king. He is on the brink of victory against Moab. Suddenly, in desperation, Mesha, the king of Moab, resorts to the ultimate counter move:

Then he took his eldest son who was to reign in his stead, and offered him for a burnt offering upon the wall. And there came great wrath upon Israel; and they withdrew from him and returned to their own land (II Kings 3:27).

The presumption is that he sacrificed his adult son much as Abraham was willing to do. According to the biblical text, the child sacrifice is successful. As a direct result of this action a divine wrath is visited upon the Israelite forces leading to their withdrawal from the land of Moab. The net result is that Israel lost and the Moabite rebellion succeeded.

Historically, there is one problem with this story. By chance, the Moabite version of the war with Israel has been discovered. According to the Mesha Stele, Moab did prevail in this war of rebellion after having been a vassal of the Israelite king Omri, the father of Ahab and grandfather of Jehoram. There is, however, no mention of a child sacrifice. Instead there is mention of Mesha having destroyed the sanctuary to Yahweh at Nebo. These references catch the eye of the biblical scholar since it is a Nebo where Moses was buried. To have a Moabite mention by name Yahweh, Israel, and Nebo is significant.

Since both versions attest the victory of Mesha over Israel, the scholarly consensus is that Mesha really did win. The defeated Israelite king needed an excuse to explain his loss. His explanation was the big lie: victory was stolen from him by this alleged act of child sacrifice by the enemy king. Otherwise, Israel would have won.

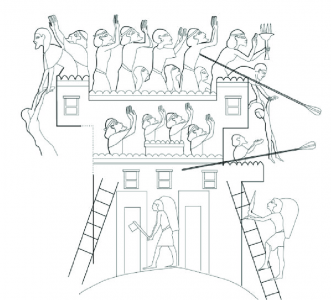

The presumption is that such an excuse for a defeat with resonate with the Israelite population. There would be no point to concocting such an explanation if the Israelite people would not have believed it. In this case, the biblical writer seems to have drawing on a Canaanite tradition. In the image shown above, the people of Ashkelon are facing defeat by Merneptah, the Pharaoh who claimed in this sequence to have destroyed the seed of Israel. They are shown dangling a child over the wall of the city. The consensus is that the act was the same as what Mesha supposedly would do centuries later: when the battle is not going well, the leader sacrifices his son to stave off defeat. The effort against Egypt was unsuccessful and the larger-than-life Pharaoh in effect mocks this gesture.

This raises the question of why the biblical writer thought the claim that Mesha sacrificed his son would work. After all, Mesha’s alleged sacrifice would be to Chemosh the Moabite god and not to Yahweh, the Israelite god. Does this mean that Chemosh is greater than Yahweh? Why should Jehoram expect that the claim that victory was stolen from him by Mesha drawing on a Canaanite tradition would be acceptable to an Israelite audience?

As it turns out, according to the biblical text Jehoram’s protestations failed as well. The prophet Elisha condemns him and his house. He commissions Jehu to lead a coup against the king. Jehu slays both the king and his mother Jezebel fulfilling prophecy.

“This is the word of Yahweh, which he spoke by his servant Elijah the Tishbite, `In the territory of Jezreel the dogs shall eat the flesh of Jezebel; and the corpse of Jezebel shall be as dung upon the face of the field in the territory of Jezreel, so that no one can say, This is Jezebel'” (II Kings 9:36-37).

The big lie about having victory stolen from the incumbent king due to a child sacrifice by his opponent did not end well for the loser and those associated with him.

What are the lessons to be learned from this partial review of biblical stories involving child sacrifice?

1. There is no biblical justification for not being vaccinated. Hiding behind the Bible is cowardly and dishonest.

2. Know your audience when promoting child sacrifice – why do you think gambling with the lives of children is a winning political move? The voice of the people in California like the voice of the prophet Elisha has been heard. People want the pandemic to end. Are Trumpicans listening?

3. Know your audience when explaining away defeat through the big lie – how many times can you tell the big lie before losing all credibility even to your own followers? After every election defeat? Even when by millions of votes?

What will the fate be for the candidate(s) of the big lie who are willing to sacrifice the children of voters?

He said, “Throw her [Jezebel] down.” So they threw her down; and some of her blood spattered on the wall and on the horses, and they trampled on her (II Kings 9:33).