2019 marked the 400th anniversary of the slavery of Africans in the British American colonies. A Federal commission was created in recognition of this event. The commission did not develop a national presence. Instead of leading a discussion on the event, it was confined to some local events in Virginia where the landing had occurred.

At the national level the most significant voice was that of The New York Times. The Sunday Magazine on August 18, the approximate anniversary date, was dedicated to The 1619 Project. According to a subsequent blurb, the issue sold out and additional copies were printed. A related podcast series was the most downloaded podcast in the United States. The Project has been turned into school curriculum with more than 3000 teachers saying they are using it. Copies were sent to over 500 schools in 91 cities and towns in 30 states. Over 200,000 free copies have been distributed to schools, libraries, museums and for various events. There is a book project underway.

All in all it is safe to say that The 1619 Project of The New York Times is a big deal. So what’s the problem?

A HISTORY COMMUNITY REACTION

There was a reaction of a different sort as well to this publication. Phillip W. Magness of The American Institute for Economic Research (AIER) is maintaining a database of these responses at The 1619 Project Debate: A Bibliography last updated January 3, 2020. It would be a project in and of itself simply to report on these critiques. A great deal of attention in them is directed against the opening historical narrative written by Nikole Hannah-Jones of The New York Times entitled “The Idea of America” (this title does not appear in the print edition). She had suggested the creation of a dedicated issue on 1619 at a staff meeting in January, 2019. She then invited 18 scholars and historians to a meeting at The New York Times for a brain storming session.

THE EDITOR’S NOTE

In this blog instead of analyzing her historical narrative or the responses to it, I will focus my comments on the six-paragraph Editor’s Note by Jake Silverstein at the beginning of the Sunday Magazine. He also is the person who responded in December to the Letter to the Editor signed by five historians who were critical of certain parts of the project.

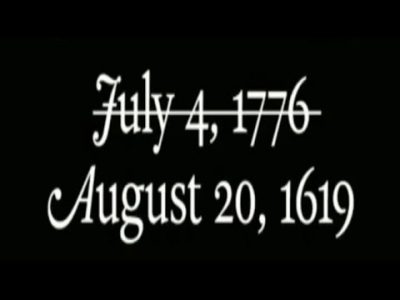

The two-page Editor’s Note begins with “1619.” in huge print spread across the pages. The opening lines are:

1619 is not a year that most Americans know as a notable date in our country’s history. Those who do are at most a tiny fraction of those who can tell you that 1776 is the year of our nation’s birth. What if, however, we were to tell you that the moment that the country’s defining contradictions first came into the world was in late August of 1619?

The claim is certainly an audacious one. It announces that the true birthday of the country should be celebrated when slavery began here and not with the Declaration of Independence. One may say that Silverstein’s use of the word “contradictions” is a way to claim that it is not the birthday of the nation that is at stake, just its “contradictions.” But then he would be comparing apples to oranges since the opening sentence specifically refers to “our nation’s birth.” The implication is that our true birth is in the contradictions and not in the declaring of our independence.

THE EDITOR’S NOTE VERSUS THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY AND CULTURE

Still in the opening paragraph, Silverstein writes:

Their arrival inaugurated a barbaric system of chattel slavery that would last for the next 250 years.

I am not sure precisely what is meant by 250 years or 1869 as the concluding date. The 14th Amendment on citizenship and rights was ratified in 1868 so perhaps that is the 250th year. The number is significant as we are beginning the 250th anniversary celebration of America’s birthday in 1776. The Boston Massacre, for example, occurred in 1770, so in Massachusetts it will start this year.

Be that as it may, the impression conveyed by the text is that for 250 years the British colonies and American states had slavery. Why 250 years? Consider for example the separate section of The 1619 Project prepared by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture with Caitlin Roper, editorial director. In that section a full page is given to a quotation from Frederick Douglass expressing “the outburst of joy and thanksgiving that rent the air when the lightning brought to us the Emancipation Proclamation.” That document was proclaimed on January 1, 1863. The Smithsonian section contains no such expression of joy on the 250th anniversary exclaimed in the Sunday Magazine.

Regardless of whether one uses 244 years or 250, it is a false message. Not even all the colonies had been founded by 1619. Outside of Virginia, no colony/state had a 250 system of slavery even assuming 1868 is the date for the end of slavery. For that matter many northern states had outlawed slavery decades earlier. Consider again the Smithsonian section. There is a box there entitled “She Sued for Her Freedom.” It tells of Mumm Bett suing for her freedom under the new Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. Her husband had died fighting in the American Revolution. Now she argued that slavery violated the rights enunciated in that document. She won and changed her name to Elizabeth Freeman. The Smithsonian concludes that item with:

Her precedent-setting case helped to effectively bring an end to slavery in Massachusetts.

This action occurred long before the 250-year period touted in the Sunday Magazine. Again, the Smithsonian section undermines the message of the Sunday Magazine.

In addition, other states were founded as free states and never had slavery. The intention to depict that all America had slavery and for 250 years is deceptive at best and outright wrong.

VIRGINIA VERSUS NEW AMSTERDAM

Furthermore, the characterization of slavery as a “barbaric system of chattel slavery” also is false. Northern European countries like England and the Netherlands had no or little familiarity with slavery. The legal codes of these countries could handle serfs but slavery was new. In New Amsterdam, the Dutch struggled for decades on the legal status of the African slaves. During that time, some Africans became free. Africans could own land did so on a farm adjacent to the farm of Peter Stuyvesant. Africans could join the Dutch Reform Church. Africans could testify in court. Africans could initiate law suits. The numbers involved were comparatively small at this time. I suspect that if New Amsterdam had remained Dutch, free Africans would have become more and more like free Dutch and that slavery would have ended long before New York began in 1799 to legally end it, again before the touted 250-year period.

Admittedly, the situation in Virginia differed from that of New Amsterdam given all the plantations. Still it took a while to develop the chattel system referred to. After all, to create a system where 75%-white Sally Hemings is black doesn’t happen overnight. The year after 1619 was not the beginning of Gone-with-the-Wind plantations. Again the Smithsonian section sheds light on the deceptiveness of the Sunday Magazine Editor’s Note. A section entitled “Race Encoded into Law” notes the passage in Virginia in 1662 that essentially defines slaves as commodities. This passage implies it took Virginia about 43 years to render a formal decision in law that slaves were property not people. Hence since Sally Hemings mother was biracial and her mother’s mother was black, she was legally a black slave too.

The point here is no to deny the barbarity of the chattel slavery system but to recognize that it did not spring forth fully formed the day after the landing in 1619 or in all the future colonies that were established. America would have been better served if The New York Times had told the story of how chattel slavery emerged in Virginia over these forty-plus years.

Why is Silverstein seeking to convey a message of a national barbaric system of chattel slavery that lasted 250 years? The answer is simple as he concludes the opening paragraph.

This is sometimes referred to as the country’s original sin, but it is more than that: It is the country’s very origin.

The message bluntly put is that We the White People of America were born in America’s original sin. We the White People of America need to repent for this sin. And The New York Times is going to show us the path to redemption.

SLAVERY DOES REQUIRE ANTI-BLACK RACISIM

Silverstein compounds the problem in the opening words of the second paragraph.

Out of slavery — and the anti-black racism it required — grew nearly everything that has truly made America exceptional…

Slavery does not require anti-black racism. Who knew Spartacus was black? The word “slave” derives from the Latin sclāvus (masculine), sclāva (feminine) from the Slavic peoples who dominated the medieval slave population in Europe. For that matter, why is it even politically correct to use the word “slave” or “enslaved” anyway? Can you say “gypped” or “jewed”? Putting that aside for the moment, there is a huge omission in The 1619 Project. It’s bad enough that Virginia is made the basis for all colonial and American history to the exclusion of what was happening elsewhere, but another gap in the storytelling is Africa itself. Hannah-Jones does mention in passing that the Virginia Africans brought by an English pirate ship were from a Portuguese trading ship that was from Angola, but that’s it.

WHERE’S AFRICA IN THE 1619 PROJECT?

Somehow the Middle Passage doesn’t have a start point. There is a lot of attention on the destination points in the Western Hemisphere. There is a lot of attention on the horrific conditions in the transportation to the Western Hemisphere. But there is minimal to no attention on the start point of that passage. In the (1500 and) 1600s, that means primarily modern Angola. Back then it meant two major kingdoms, Kongo and Ndongo(/Matamba) with a Portuguese colony of Angola named after the founding king of the Ndongo kingdom. The ignorance of the importance of Angola can be seen in the 400th anniversary trip to Africa by the NAACP. Where did they go? To Ghana. Going to Ghana for the 400th anniversary of slavery in Virginia makes about as much sense as going to England to honor Ellis Island immigrants.

The Smithsonian section introduces a slightly different picture. It notes the Romanus Pontifex of 1455 “which affirmed Portugal’s exclusive rights to territories it claimed along the West Africa coast and the trade from those areas.” The Smithsonian quotes from the affirmation that Portugal had the right regarding the people it encountered to “reduce their persons to perpetual slavery.” But it excludes the reference to “Saracens” which was the whole point of the expeditions. With the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Moslems now encircled Europe cutting off access to both Slavs to serve as slaves and trade with Asia. There was the hope among Catholics that they could do an end-around by sailing south around Africa. In 1455, they didn’t know how far the coast extended. The Portuguese would not reach Ghana until the 1470s and Kongo until 1482. It should also be noted that Portugal was not even aware of the Western Hemisphere at this time.

Evidence of these sailings as part of a religious confrontation and not a racial one may be seen in the actions in Kongo. The king of Kongo was baptized in 1491. Missionaries began baptizing Kongolese in droves. Free Kongolese sailed to Lisbon to be educated. Diplomatic correspondence between Kongo and Portugal and the Vatican commenced. One Kongolese married into the royal family approximately 500 years before Meghan Markle. In the 1600’s Ndongo/Matamba entered into extensive relations with the Vatican in its quest to be recognized as a Christian kingdom. Kongo and Ndongo/Matamba were independent countries and represented Catholic outposts in the confrontation with Moslems. At this point in time, slaves were people not property and slavery was not based on anti-black racism.

Same-race slavery in Africa is another omission from The 1619 Project. In the Travel section of The New York Times, Jacqueline Woodson wrote Finding Pain and Joy in Ghana about her trip there as part of the 400th anniversary (December 15, 2019, print). On the Ghana invitation to descendants of which she is one, Woodson writes

In its efforts to bring the African diaspora together, Ghana’s leaders are also hoping to make amends for the complicity of Africans in selling their own people in what would become the trans-Atlantic slave trade….

…I found myself struggling to come to terms with those who worked with white traders to move black bodies into chattel slavery.

She quotes a passage from Henry Lewis Gates in Ending the Slavery Blame-Game published in The New York Times, April 22, 2010.

The sad truth is that without complex business partnerships between African elites and European traders and commercial agents, the slave trade to the New World would have been impossible, at least on the scale it occurred…. But the sad truth is that the conquest and capture of Africans and their sale to Europeans was one of the main sources of foreign exchange for several African kingdoms for a very long time. Slaves were the main export of the kingdom of Kongo; the Asante Empire in Ghana exported slaves and used the profits to import gold. Queen Njinga, the brilliant 17th-century monarch of the Mbundu, waged wars of resistance against the Portuguese but also conquered polities as far as 500 miles inland and sold her captives to the Portuguese. When Njinga converted to Christianity, she sold African traditional religious leaders into slavery, claiming they had violated her new Christian precepts.

The Smithsonian section also mentions Njinga. It focuses on her exploits as a freedom fighter against the Portuguese. There is no mention of her as a slave-owner or slave-trader. There is no mention of her alliance with the Dutch against the Portuguese or of her purchase of guns and ammunition in exchange for slaves. There is no mention of becoming Catholic and trying to create a Catholic kingdom with extensive correspondence with the Vatican. Think also about the 500 miles mentioned by Gates. Now imagine the Tuscarora in Buffalo rounding up captive Indian tribe slaves, marching them to New Amsterdam, and selling them to the Dutch to be transported as slaves elsewhere. But Njinga gets a pass on her slave-owning and slave-trading in her fight against the Portuguese that Thomas Jefferson on a much smaller scale does not get. There was no abolition movement in Angola.

Frederick Douglass commented on this issue of African slave trade as well. With all the fuss about colonization and Abraham Lincoln in The 1619 Project, it is important to remember what Douglass had to say and which should be included in any school curriculum.

Depend upon it, the savage chiefs on the western coast of Africa, who for ages have been accustomed to selling their captives into bondage, and pocketing the ready cash for them, will not more readily see and accept our moral and economical ideas, than the slave-traders of Maryland and Virginia. We are, therefore, less inclined to go to Africa to work against the slave-traders, than to stay here to work against it. (“African Civilization Society,” February 1859)

Why should Middle Passage blacks give up their white masters in the United States for the black ones in Africa who willingly, eagerly, and freely sold them to white people in the first place? Wouldn’t that make for a good high school essay topic?

1619 VERSUS 1776: THE BATTLE IS ENGAGED

With this background in mind, let us return to the original issue of replacing 1776 with as 1619 as the birth of the country and revising the school curriculum and national culture accordingly.

The 1619 Project of The New York Times is a direct assault on what Abraham Lincoln accomplished. Prior to him, one said “The United States are a country.” After him, one said as we still do to this very day, “The United States is a country.” It was Lincoln at Gettysburg who redefined America from being a collection of states to being a We the People country. Lincoln deserves credit not just for making Thanksgiving a national holiday for all Americans even if you were not of Pilgrim descent but for redefining July 4th as well. When Lincoln said “Fourscore and seven years ago, our fathers…” he knew that not everybody in the audience was a son or daughter of the American Revolution. He asserted that to stand for the Union then was to stand with the Founding Fathers in 1776. That principle has applied to all naturalized Americans since then.

Obviously not all Americans agreed with Lincoln’s vision then nor do they now. Most famously, Robert E. Lee self-identified as a Virginian and not an American. In effect, his Founding Father was John Smith and not the Founding Fathers we know today or who perform in Hamilton.

America at its birth consisted not only of many states but many peoples. There were Africans, Dutch, French Huguenots, German Palatines, Irish Catholics, Scotch Irish, and Sephardic Jews just to mention the main non-English ones. In addition there were English Anglicans, English Pilgrims, English Puritans, and English Quakers. And then there were the multiple Indian nations/peoples who thought of themselves as independent entities in their own right. To create a collective We the People from that mixed multitude was and is no easy task.

How many multi-religious countries were there in 1776 where people of all religions had the same rights?

How many multi-ethnic countries were there in 1776 where all ethnicities had the same rights?

How many multi-racial countries were there in 1776 where all races had the same rights?

The American story of exceptionalism has many points of origin leading to July 4 which did not grow out of 1619.

1607 with John Smith and Pocahontas

1620 with the Pilgrims and Thanksgiving

1624 with the Dutch and the Island at the Center of the World

1630 with the Puritans and the City on a Hill.

All contributed to the story of America. There is no problem with adding 1619 to this list. Indeed, it should be. There is a big problem with deleting those dates and 1776 and replacing them with 1619 as the origin of America or as the basis of “nearly everything that has truly made America exceptional.”

Consider this date which also could be added to the list. The first black to arrive in New Amsterdam was Juan (Jan) Rodriguez in 1613, six years before 1619. He was a free person of Portuguese and African (probably Angolan) descent. He married into a local Lenape tribe. His story then combines multiple races and ethnicities. In October, 2012, the New York City Council enacted legislation to name Broadway from 159th Street to 218th Street in Manhattan after him. The neighborhood today is Dominican so the location is in tribute to Rodriguez’s place of birth. The location is around 120 blocks from The New York Times. So how about making 1613 the new birthday in recognition of the Island at the Center of the World and the expression of e pluribus unum through the life of Juan Rodriguez?

Our country is not defined by race, ethnicity, religion, or a geographic location but by an idea. The Founding Fathers built on the strands that came before them to start to weave multiple peoples into a unity. Abraham Lincoln continued that effort by including people who were not biological sons and daughters of the American Revolution as ideological sons and daughters if they stood with the Union. Irish who sang Yankee Doodle Dandy continued that journey of being included as Americans. Ellis Island immigrants who sang God Bless America continued that journey of being included as Americans. Middle Passage blacks who said “I have an American dream” and helped America land on the moon continued that journey of being included as Americans. The 250th anniversary of the American Revolution provides us with a desperately needed opportunity to continue that journey in the 21st century with many new peoples who are proud to be Americans and celebrate July 4th.

The 1619 Project represents a giant step backward away from continuing that journey. The front page article of today’s New York Times (“Two States. Eight Textbooks. Two American Stories.”, January 13, 2020) is about the divided history textbooks of our divided nation. The political reporting of the newspaper testifies to the importance of the hostility to the politically correct in the 2016 presidential elections, a far bigger factor than Putin. Now The New York Times has decided to promote and aggravate the division of the country just as our President does at the precise time when we need to heal and unite as We the People. The New York Times has given us a false history that is woke but not helpful. What a wasted opportunity.