The battle for the American Revolution continues. Since The New York Times threw down the gauntlet in August 2019, the war over the War has been engaged. This is not to say that the war had not broken out earlier. However with the publication of the 1619 Project the battleground has become clearer and more defined. The shortcomings of the 1619 Project have been the subject of previous blogs (The Battle between 1619 and 1776: The New York Times versus the History Community, 1619: The New York Times versus USA Today (and Hamilton), Happy 1619, Not July 4th, Birthday: All the History Fit to Print that the NYT Omitted). These problems mainly concern 1619 itself, a year strangely absent from the public battle which has raged since the publication.

A case in point is the most recent showdown between the forces of light and darkness involving two prominent American historians:

Woody Holton, the McCausland professor of history at the University of South Carolina

and

Gordon Wood, the Alva O. Way university professor and professor of history emeritus at Brown University.

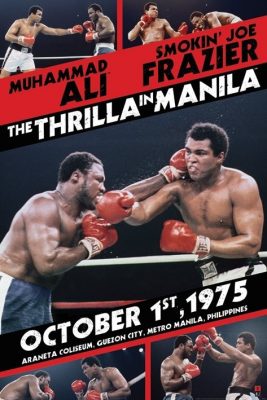

The venue was the Massachusetts Historical Society for a hybrid showdown on October 23, 2021. As befitting this heavyweight match, it was recorded and covered in the press.

THE PRELIMINARY MATCHES

The prefight fisticuffs began with a July 2, 2021, publication by Holton in the Washington Post entitled “The Declaration of Independence’s debt to Black America: When African Americans allied themselves with the British, the Patriots were enraged, and they acted.” In this first punch, Holton stated that “African Americans played a crucial, if often overlooked, role in their White owners’ and neighbors’ decision to declare independence from Britain.”

Holton makes his case by starting in Virginia in 1774, five months prior to the shooting engagement at Lexington and Concord. In this instance, he meeting Holton was referring to was one by Africans who were pondering how to exploit the White conflict to obtain their own freedom. Holton contends that for the following year, the Africans pitched the idea to the British that the outnumbered British needed the numbers the Africans could provide. Eventually that argument prevailed and Lord Dunmore accepted African participation on the British side in exchange for emancipation.

The White response was much as it has been to Critical Race Theory [not Holton’s term}. It was one of fury. Indeed the fury was of such magnitude that it pushed on-the-fence White Americans to endorse the Patriot call for independence. According to Holton, the British kept their promise and resettled over 3000 Africans to Nova Scotia in 1783. As part of the Evacuation Day, November 25 commemoration [Thanksgiving this year], the Lower Manhattan Historical Association [LMHA, me included] will be celebrating it on November 24 this year.

That punch led to a counterpunch, On 1619 and Woody Holton’s Account of Slavery and the Independence Movement: Six Historians Respond on September 6, 2021, by

Carol Berkin, Baruch Presidential Professor of History, City University of New York

Richard D. Brown, Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of History, Emeritus, University of Connecticut

Jane E. Calvert, Associate Professor of History, University of Kentucky, and Director/Editor, the John Dickinson Writings Project

Joseph J. Ellis, Professor of History, Emeritus, Mount Holyoke College

Jack N. Rakove, William Robertson Coe Professor of History and American Studies and Professor of Political Science, Emeritus, Stanford University

Gordon S. Wood, Alva O. Way University Professor and Professor of History, Emeritus, Brown University.

In this counterpunch, these warrior historians took aim at Holton’s support of the 1619 Project of The New York Times. They objected to the “unusual claim” that protection of the institution of slavery was the cause of the support for the Patriot side. By the time of Lord Dunmore’s proclamation, Virginia already favored the call for independence and were de facto operating on that basis. They cite the recent book by Mary Beth Norton, former president of the American Historical Association on 1774 to substantiate the claim that the colonists already were effectively independent.

Note: Norton’s book entitled 1774: The Long Year of Revolution actually is about 1774 whereas the 1619 Project is not at all about 1619 at all. If 1619 was a person, it could sue The New York Times for false advertising.

In this counterpunch, these heavyweight historians assert that the colonist independence movement had generated enough momentum prior to the events cited by Holton, sufficient to render his claims moot. They delivered another blow by introducing the phenomenon of the anti-slavery movement in Philadelphia in 1775. So not only is Holton wrong about the American Revolution being based on the goal of preserving slavery, it lead to the movement to abolish it. They close by citing three people who valued the words of the Declaration of Independence: Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, and Martin Luther King.

That counterpunch led to a counter-counterpunch by Holton, The Specter of Emancipation and the Road to Revolution: A Rejoinder to Richard Brown et. al. on September 8. He stated that he was flattered and saddened by the previous article. He was flattered due to the prominence of the authors but saddened that they cannot see what was right before them as historians. He added one piece of new evidence: the 26th charge against King George in the Declaration that he had “excited domestic insurrections amongst us” meaning slave revolts [aka revolts by enslaved people]. He calls #26 “the capstone” based on the presumption that by point 26 people are still paying attention and as much as they did with #1.

Holton pushed the clock back to 1762 [not 1619] with the end of the French and Indian [Indigenous] War. At that time the colonists were content to be subjects of the British Empire; by 1774 they were not. What had happened in the interval? He claims that “one” of these factors was England’s cooperation with the colonists “slaves” [enslaved people]. “It was not the reason, but it was a reason.” The italicized words are from Holton.

He rejected the proposition that the colonists were already headed towards independence. He promised that his new book would supply the evidence for his “staged-based view of the road to independence.” He regretted that the distinguished professors responded to his 700-word Washington Post article to promote his upcoming 700-page book rather than wait for its publication. As a tactical move it seems shortsighted to expect everyone reading his column would remain silent until after the book publication.

Holton closed with a 1 in 26 and “a” and not “the” cause plea that called for the inclusion of slavery as a cause which makes one wonder what all the fuss is about. If he is not going to make slavery the defining cause of the American Revolution, then why the big fight?

THE MAIN EVENT

The main event drew wide press coverage but did not live up to its hype. The history debate was covered by the Associated Press which made it unusual. It also assured more widespread national coverage than if simply covered by a local paper or a specialized newsletter.

According to the World Socialists, during the first part of the match, Holton was getting beat up for his former position on the Dunmore Proclamation as being the instigator of shift towards independence by White people. The World Socialists describe blow after blow being received by Holton as he admits colony by colony that Dunmore was not a factor in those areas. Gradually the impact of the Coercive Acts in 1774 pushed by Wood became a factor in the historical reconstruction of the path toward independence over one year before Dunmore.

At this point, Wood seemed to have Holton on the ropes historically although I am not quite sure all viewers of the recording would think so. The World Socialists cited this query from a viewer to a flummoxed Holton as the decisive moment:

“If it were the case that the defense of slavery was the major cause, or a primary cause, of the American Revolution, then why did the British possessions in the Caribbean, where slavery was even stronger, not join the revolution? Why did they remain the most loyal area of the empire?”

At that point, the debate about the American Revolution shifted to the political arena. According to the Hillel Italie (AP):

But midway through the 60-minute event the subject turned to The New York Times’ 1619 Project, the Pulitzer Prize winning series from 2019 that placed slavery at the center of the American narrative. The mood soon resembled less a spirited, but academic gathering than a court of law, with Wood on the stand.

According to William Hogeland, Slate, “The Historians Are Fighting: Inside the profession, the battle over the 1619 Project continues”:

It devolved into a long, loud sequence when a revved-up, happy-warrior Holton started fast-talking over and relentlessly haranguing a clearly irritated Wood, who was reduced to defensive sputtering.

Tom Mackaman, World Socialists, phrased it slightly differently:

Not even halfway through, Holton was given a lifeline by moderator Catherine Allgor of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Allgor moved the discussion to Nikole Hannah-Jones, the celebrity figurehead of the 1619 Project. Getting his cue, Holton went on the attack.

Suddenly it was a brand new ball game. The supposed history debate took a sharp turn for the worse and became a political mud wrestling confrontation. Holton said (AP):

“You are a founding father, Professor Wood, of a massive campaign of censorship. You’re not the most responsible, but the five of you are responsible. And that’s why, right now, I want to ask you to write another open letter to Sen. Cotton, and to Gov. DeSantis, and to all the other demagogues who are using your letter to ban the 1619 project, to say, ‘I am Gordon Wood, and damnit, I am not in favor of censorship.’”

The World Socialists described this turn of events as follows:

However, most of the hourlong debate was given over to provocations from Holton, who repeatedly accused Wood and other scholars who have criticized the New York Times ’ 1619 Project of being responsible for Republican Party efforts to censor it. Holton’s opposition to censorship is, to say the least, highly selective. While he opposes Republican efforts to censor the 1619 Project—as does the World Socialist Web Site —he denounces and would silence all criticism of the 1619 Project from left or scholarly perspectives, as his attacks on Wood made clear.

Hogeland succinctly described the change in debate as:

…intensifying a recent trend in modes of dispute among scholars of the founding period…. Venerable traditions of academic history haven’t usually included mano a mano contests on fine points of interpretation, held for the excitement of the baying crowd or, as in this case, the edification of decorous history buffs.

He calls them the “two pugilists.” This turn of events represents the future of American historians. As they leave the ivory tower and become participants in the Culture Wars/Civil War, they will increasingly ask or be asked to take a stand in that war such as on the 1619 Project. As a result, historians like Supreme Court judges will become partisans and lose their image of impartialness or objectivity [Note – “objectivity” has been designated a racist white characteristic which should not be imposed on non-white people.] Welcome to the brave new world of history mud wrestling. Are you ready?

This line-in-the sand and 1619 intrusion into everything becomes clear in the post-match interviews conducted by the AP.

During a telephone interview a few days later, Wood called the debate a “disaster,” said he was “blindsided” by Holton’s attack and that Holton was carrying out his role as “the primary defender” among historians of the 1619 project. Asked if he found any positive qualities in the series, which includes essays on politics, culture, criminal justice and religion among other subjects, he criticized it for encouraging a sense of “victimhood” and feeling “aggrieved” that he called understandable but ”self-destructive” in the long run….

“I had no idea of what DeSantis was doing,” he said of the Florida governor, who has labeled the 1619 project “critical race theory” and backed the state’s board of education’s decision last summer to ban the book from classrooms. “It’s out of my hands. We can’t do our historical research … (worrying) that it might be misused by politicians.”

Speaking of politics, consider this description of Holton by the World Socialists:

Instead, Holton’s conception of the American Revolution is tailor-made to meet the present political needs of the Democratic Party. Unlike Beard, and much more akin to the old Jim Crow-era “folkways” social scientists, Holton claims to deduce the historical action of the Revolution by imposing on the past the identity categories of the present, particularly the racial ones. His “method” entails the deployment of what he calls “pieces of evidence,” carefully selected and ripped from their context, to prove his “point” and the disregarding of evidence to the contrary.

Holton’s father is Linwood Holton, a Republican governor of Virginia who became a Democrat, and his brother-in-law is Virginia Senator Tim Kaine, Hillary Clinton’s vice presidential running mate in 2016. The family’s fortune is drawn from western Virginia coal mining, certainly one of the most exploitative industries in American history. These biographical facts may go some distance in explaining Holton’s fealty to the 1619 Project, which is central to the Democratic Party’s efforts to eradicate discussion of social class in the past and the present.

Welcome to the new reality. The past is only not past, it is the political mud wrestling arena present and future.