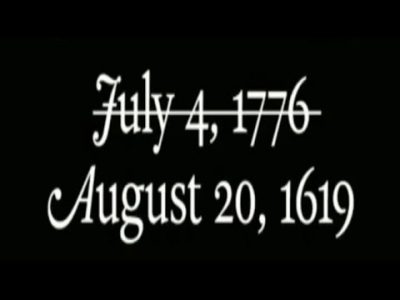

Even without the coronavirus, the United States should not be celebrating July4th as its birthday according to The New York Times. In its Pulitzer-Prize winning Sunday Magazine issue entitled “1619” (August 18, 2019), The New York Times asks us to accept 1619 as the true birth year of the United States and not 1776 (see the blog The Battle between 1619 and 1776: The New York Times versus the History Community). It claims that a ship carrying “a cargo of 20 to 30 enslaved Africans” marks the country’s origins. It does so even though no country existed at that time and there weren’t even close to 13 British colonies then either.

As one might expect, there was a negative reaction to this publication. For the most part the NYT was able to swat away these responses. What was striking about them was that they were mostly about the American Revolution and Abraham Lincoln. Hardly anyone commented on about the attempt to redefine American history by having it originate not with the Declaration of Independence but with “original sin.”

In some ways the lack of comments on 1619 was not surprising – there was hardly anything written in the magazine about 1619! One would think that in a magazine with the title “1619,” there would be at least one article devoted to that topic. Instead it was almost absent save for a few stray comments here and there that mentioned 1619 in passing. The supplement contains more information. But if you really wanted to know about 1619, you are far better off reading the vastly superior account in USA Today [see my blog 1619: The New York Times versus USA Today (and Hamilton)].

There were a few comments that directly addressed the year in question. For example, Nell Irvin Painter, Princeton University, wrote (How We Think about the Term ‘enslaved’ Matters):

People were not enslaved in Virginia in 1619, they were indentured. The 20 or so Africans were sold and bought as “servants” for a term of years, and they joined a population consisting largely of European indentured servants, mainly poor people from the British Isles whom the Virginia Company of London had transported and sold into servitude.

Enslavement was a process that took place step by step, after the mid-17th century. This process of turning “servants” from Africa into racialized workers enslaved for life occurred in the 1660s to 1680s through a succession of Virginia laws that decreed that a child’s status followed that of its mother and that baptism did not automatically confer emancipation. By the end of the 17th century, Africans had indeed been marked off by race in as chattel to be bought, sold, traded, inherited and serve as collateral for business and debt services. This was not already the case in 1619.

How come The New York Times didn’t know this? As you can see from Prof. Painter’s comments, the slavery system developed ad hoc over time as new situations occurred. For example, suppose someone was baptized, then what? Suppose someone had a white father and a black mother, then what? The system whereby 75% -white Sally Hemmings was legally both black and a slave did not exist in 1619. It took time for different combinations and circumstances to develop.

What then should be done to redress the shortcomings, omissions, and errors in the NYT’s publication? The answer is fairly straightforward. Have a conference or conferences to plug the gaps and provide the information that was to fit to print in “1619” but wasn’t. Specifically, there are 5 topics which should be covered by my count.

1. Where’s Africa?

According to a recent NYT note on the “1619” publication, an earlier draft by Nikole Hannah-Jones began the story earlier than July 4th and the American Revolution (“Telling ‘the Sweep of 400Years’,” June 18, 2020, print). It began with the Middle Passage where she wrote “They say our people were born on water.” I don’t know who “they” are in the sentence but that beginning would have been a step in the right direction. It’s still not Africa, but it’s closer. The phrase was used by Tiya Miles in “1619” who then mentions the Mbundu, Akan, and Fulani peoples. But the phrase ignores what the people of the Middle Passage brought with them from Africa to the Western Hemisphere. It’s as if the Middle Passage had “severed them so completely from what had once been their home that it was as if nothing had ever existed before, as if everything and everyone they cherished had simply vanished from the earth.” The presence of the King of the Kongo at Pinkster celebrations demonstrates that not everything had vanished. What was this kingdom and why was its king remembered?

The story “out of Africa” should begin in Africa. If the focus is 1619, then the area of concern is the modern country of Angola. No such country existed in 1619 and no people there self-identified as “Angolans” then either. However it is the region that produced over 5 million of the 12 million people brought to the Western Hemisphere, especially Brazil, and was the source of people on the vessels that were captured by pirates and brought here. The study would explore the Kingdom of Kongo and the Mubundo and Imbangala peoples as they were the ones most involved in the slave trade. There are scholars with expertise in this subject who could have been consulted in the preparation of “1619” and who could be invited to do a session, symposium, or conference on it.

2. Where’s Europe?

Similarly there is a story to be told about the Europeans who were involved in 1619. The key people are the Portuguese who arrived in Kongo in 1481. What were they doing there? How did it happen to be that the Portuguese were making the difficult voyage south along the African coast (going south was easy, it was the return north that was the challenge)? What did slavery mean in the European tradition? Why were owned people called “slaves” anyway? What was the geo-political situation at the time including Christian-Moslem and Protestant-Catholic? Why did the Dutch and the English get involved? These relationships are important. In 1491, the Kongo king voluntarily became Catholic beginning a long relationship between the independent country (not a colony) and the Church. In 1618, the Thirty Years War began which included the Kongo as well. There are scholars with expertise in these subjects who could have been consulted in the preparation of “1619” and who could be invited to do a session, symposium, or conference on them.

3. Where’s the Slave Trade?

How did the people who were brought to first the Atlantic Islands and Europe and then to the Western Hemisphere come to be brought to these areas? What were the mechanisms by which so many people could be brought to the Western Hemisphere by so few people? Miles uses the phrase “people stolen from western and central Africa.” This phrase expresses a popular explanation (see Roots):

Spike Lee: “just the fact that we were stolen from Mother Africa and brought here through the Middle Passage… (Time, June 22-29, 2020, print).

Other people take a different view.

Frederick Douglass:

Depend upon it, the savage chiefs on the western coast of Africa, who for ages have been accustomed to selling their captives into bondage, and pocketing the ready cash for them, will not more readily see and accept our moral and economical ideas, than the slave-traders of Maryland and Virginia. We are, therefore, less inclined to go to Africa to work against the slave-traders, than to stay here to work against it. (“African Civilization Society,” February 1859)

Henry Louis Gates: The sad truth is that without complex business partnerships between African elites and European traders and commercial agents, the slave trade to the New World would have been impossible, at least on the scale it occurred…. But the sad truth is that the conquest and capture of Africans and their sale to Europeans was one of the main sources of foreign exchange for several African kingdoms for a very long time. Slaves were the main export of the kingdom of Kongo; the Asante Empire in Ghana exported slaves and used the profits to import gold. Queen Njinga, the brilliant 17th-century monarch of the Mbundu, waged wars of resistance against the Portuguese but also conquered polities as far as 500 miles inland and sold her captives to the Portuguese. When Njinga converted to Christianity, she sold African traditional religious leaders into slavery, claiming they had violated her new Christian precepts. (Ending the Slavery Blame-Game, The New York Times, April 22, 2010).

Who is right? There are scholars with expertise in this subject who could have been consulted in the preparation of “1619” and who could be invited to do a session, symposium, or conference on it.

4. Where’s Virginia?

As Prof. Painter’s comments on “1619” indicate, there is a story to be told about what happened in Virginia in the 1600s. The people who were legally free, though indentured, when they landed in Virginia, paved the way for the slavery system The New York Times took granted existed in 1619. That story would include the values the English settlers brought with them to Virginia including on slavery, free people, and servants. It includes the values of the English Puritans and Anglicans who settled in Virginia. It includes the values of small landholders and tobacco plantation owners in Virginia. There are scholars with expertise in these subjects who could have been consulted in the preparation of “1619” and who could be invited to do a session, symposium, or conference on them.

5. Where’s New Amsterdam?

The importance of the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam is that it provides another example of a colony going through some of the same issues that occurred in Virginia at the same time. It does so with a different cultural background. New Amsterdam began as a trading port or merchant city that would become an “island at the center of the world.” Later on, it expanded northwards and created “manors” including here in Westchester where I live. The environment here was not conducive to tobacco. The church here was Dutch Reform and not Anglican or Puritan. I mention these points to suggest that the Virginia model, which itself required decades to finalize, is not the only model for understanding slavery in the colonial period. Virginia and New Amsterdam both struggled with the defining the meaning of slavery and the place of Africans in their respective colonies. There are scholars with expertise in these subjects who could have been consulted in the preparation of “1619” and who could be invited to do a session, symposium, or conference on them.

By coincidence, I just received an eblast from the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture announcing an online conversation on “Slavery and Freedom in the Era of Revolution” focusing on abolitionism. The series of conversations will be based on The New York Times 1619 Project-related event “Slavery and the American Revolution: a Historical Dialogue” (March 6, 2020) held in New York involving several scholars.

I also just received a notice from the American Historical Association of a webinar to be held July 2 on “Erasing History or Making History? Race, Racism, and the American Memorial Landscape” including Annette Gordon-Reed, Harvard University, who participated in the March 6th event above.

Even in the time of Covid-19, it is possible to discuss topics such as the ones I listed above and there are organizations conducting similar type discussions. The issue is does anyone really want to know about 1619?