The baseball playoffs are upon us. How does one measure the value of players to their teams?

The answer was made famous in the book and the movie “Money Ball” starring Brad Pitt. In it the Oakland A’s manager brings a new technique to determining the value of an individual to a team. The movie ends with Pitt turning down an opportunity to manage the Boston Red Sox. That team adopts the technique and goes on to win the World Series. Now WAR has become ubiquitous in Major League Baseball. It provides a standard through which people can assess the value of someone else.

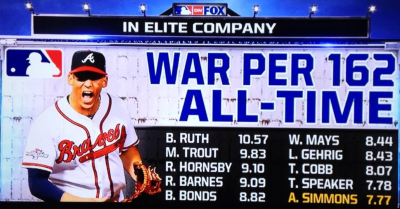

Wins Above Replacement or Wins Above Replacement Player, commonly abbreviated to WAR or WARP, is a non-standardized sabermetric baseball statistic developed to sum up “a player’s total contributions to his team”. A player’s WAR value is claimed to be the number of additional wins his team has achieved above the number of expected team wins if that player were substituted with a replacement-level player: a player who may be added to the team for minimal cost and effort.

Individual WAR values are calculated from the number and success rate of on-field actions by a player (in batting, baserunning, fielding, and pitching), with higher values reflecting larger contributions to a team’s success. WAR value also depends on what position a player plays, with more value going to key defensive positions like catcher and shortstop than positions with less defensive importance such as first base. A high WAR value built up by a player reflects successful performance, a large quantity of playing time, or both. (Wikipedia)

Although commonly used in baseball which is rich in statistics, suppose the concept was applied in history as well? What is the WAR of Thomas Jefferson?

SEVENTY-FIVE PERCENT WHITE SALLY HEMINGS

The more typical approach is the judgmental Puritan approach. You are perfect or you are toppled. This approach is the one commonly used with Thomas Jefferson over his relationship with seventy-five percent white Sally Hemings.

What did seventy-five percent white Sally Hemings think of the relationship?

How did seventy-five percent white Sally Hemings self-identify?

These questions are harder to answer. Instead what people in the present do is they decide what she should have thought and how she should have identified. Then they impose their views on the past and conclude: “See. She is an oppressed person of color and gender. Therefore Thomas Jefferson deserves to be toppled and his contribution to the Declaration of Independence should be ignored.”

But Sally Hemings had options. For example, the book Brooding Over Bloody Revenge: Enslaved Women’s Lethal Resistance by Nikki M. Taylor is reviewed in the current issue of the Journal of the Early Republic (44:3 Fall 2024). The author is quoted as stating

My argument is simple: enslaved women did, in fact resist slavery with deadly violence and when they did, their own ideas about injustice were a central motivation.

According to the reviewer;

Black women were savvy and clear about their intent when committing murder and that they stood on their own conviction that those murders were just…. Every woman Taylor includes in her study knew that even planning to attempt to harm an enslaver could mean her death.

Seventy-five percent Sally Hemings never took this path? Why not? Any answer would be speculative but the woke approach simply is inadequate for someone who had method and opportunity but apparently not motive.

A similar fate has befallen Philip Schuyler, father in-law to Alexander Hamilton. His statue in Albany has been removed. His efforts in the American Revolution on behalf of the Oneida Nation count for nothing. Perfection is the only standard.

Another example is the statue Teddy Roosevelt in front of the American Museum of Natural History. Rather than look at his total contribution to American history, he is judged by the same perfection standard. Why not just add a Rough Rider statue?

Is Andrew Carnegie a philanthropist or Robber Baron? This high school social studies question is an example of a rigged question. What is the value of the public library to the social fabric of a community? How has that increased with Covid? Historic figured should not be frozen in time. The value of Carnegie’s philanthropy has increased in time as the value of the library has correspondingly increased.

Think of the Emancipation Memorial. This memorial was “conceived of and paid for by freedmen, particularly veterans (A Monument to Black Resistance and Strength,” Chris Myers Asch and George Dereck Musgove, August 5, 2020, Perspectives Daily). The statue of “Lincoln and a Kneeling Slave” grated on people when it was unveiled on April 1, 1876 before President Grant, the Supreme Court, members of Congress and thousands others. Frederick Douglass delivered the keynote address. He subsequently wrote a letter to a local newspaper arguing for another monument in Lincoln Park with “’the negro…erect on his feet.’” However it became “a focal point for celebrations” and remained so until the completion of the Lincoln Memorial. Later the National Council of Negro Women commissioned their own statue of its founder Mary McLeod Bethune. The calls for the removal of the Emancipation Memorial ignore the history of the memorial, a history that is worth preserving:

Some contemporary activists embrace a dogmatic approach to history that “cancels” any historical figure of image that may be interpreted as racist.

The Emancipation Memorial has changed over time. People took ownership of the memorial and imbued the first statue commission and paid for by freedmen with new meanings.

The WARs in history is not static.

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

Let’s examine this situation more closely. On July 4, 1776, how many people in the world owned other people? How many in the United States did? How many wrote the Declaration of Independence?

In American history, contributing to the writing of the foundational document at the birth of the country rates fairly high WAR. While the numerical precision of baseball is not possible in history, it is fairly reasonable to conclude that Jefferson’s contribution ranks high.

Not only that, but its WAR has increased in time. The very words of the Declaration of Independence have been used by people originally excluded from consideration. In fact not only have other peoples in the United States proclaimed their rights under its umbrella but people from around the world have championed their own freedom with those words. Here we have a test case of the doctrine that we are a city on a hill and the eyes of the world are upon us. The greater the reach of American culture, the greater the impact of the Declaration. For Thomas Jefferson, his WAR has increased over time not only in the United States but throughout the world.

FREE THE SLAVES

Another criticism of Thomas Jefferson and the other Founding Fathers has been due to their failure to abolish slavery when constituting the United States as a country. This grievous sin has been used to negate everything else that they accomplished. Putting aside such narrow-minded thinking for a moment, let’s engage in some counterfactual thinking: what if they had freed the slaves in 1787, what would the benefit to the Africans have been?

As it turns out, there are three examples where something similar did happen in American history.

1. Juneteenth – As a result of the Union victory in the Civil War, slavery came to a fairly abrupt end in the South. In some ways, this event as close as possible matches what Jefferson and others are criticized for not doing. So how did the sudden end of slavery work out for the people who until just moments ago had been slaves?

Do the following terms come to mind?

Jim Crow

Lynching

KKK

Chain gangs

No vote.

Lonnie G. Bunch III, director of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, weighed in with these thoughts in “The Archive of Emancipation” about the situation following the Civil War (The Atlantic December 2023). His own great-great grandmother even became part of the story. That story was a brutal one. It is one of people who aspired to an America that had made promises but had not delivered.

One critical development was the Freedmen’s Bureau. It lasted from 1865 to 1872. It provided the infrastructure through which people could transition from slavery to freedom. Nothing comparable exists today to assist people transitioning from prison to freedom. Nothing comparable would have been created in 1787 if slavery had abruptly ceased then. The newly freed would have been on their own subject to the violence from the dominant white society that it experienced under Reconstruction and afterwards.

Ending slavery did not end racism. Ending slavery did not provide people with a means to earn a living and raise a family. Obviously, it can be noted that some of these same conditions apply today. Condemning Thomas Jefferson and others for not ending slavery does not examine the full scope of the situation faced by the Africans if they had been freed.

2. Great Migration

The response by many newly-freed Africans was what only a handful had been able to do in the Underground Railroad. In previous blogs I have compared these people who voted with their feet to reach the north via train with immigrants like the Italians and Jews who arrived at Ellis Island. All three people were succeeding in living the American Dream although with some differences as seen in baseball. For the European immigrants this was the time of the American melting pot. For the people of the Great Migration it was the time of the New Negro, an historical period shunned by too many people today because of their inability to say the other N-word.

Obviously the situation was not the same for these three immigrant people to the North.

Redlining

Urban Renewal (aka “Negro Removal”)

Interstate Highway

And such decisions as Social Security, the G.I. Bill, the closing of schools, and the lack of trees in those neighborhoods among other actions all undermined the freedom the people of the Great Migration had won by moving to the North.

3. Civil Rights

The third and final mass “movement” occurred when the vote was extended in practice to people particularly in the South. For a while the federal government stepped in to insure the right was available and accessible. Now we have gerrymandered districts, voter suppression on registration and voting, and a step back as if the civil rights legislation never had been passed.

In hindsight, what do you think would have happened if suddenly all slaves in the South had been freed in 1787? Which of these three paths which actually happened in American history is the one most likely to have occurred if Thomas Jefferson and the other slaveholders had freed the slaves at the birth of the country?

The calculation of WAR is much more difficult in history than baseball. In history we get to impose are views on the past. In history one needs to weigh far more factors involved than one does in baseball including the fact that historical figures lived in their present and not ours. Plus the words of the Founders also became aspirational in unexpected ways, words that we can measure ourselves against today.

What’s our WAR?