The post continues the examination of the multi-authored section of the Journal of the Early Republic (JER 41 Summer 2021) dedicated to David McCullough’s The Pioneers: The Heroic Story of the Settlers Who Brought the American Ideal West. This new feature called Critical Engagements represents an attempt by the Society of Historians of the Early American Republic (SHEAR), the publisher of the journal to determine:

1. how his book would fare if it had been written as an academic book subject to peer review

2. what can academic historians learn from authors of such popular “airport” or “(white) Fathers’ Day” books about how to reach a larger audience.

In the previous post, I presented:

1. guidelines for general public speaking by Connecticut State Historian Walt Woodward

2. an example of the way to alienate the general public by telling (white) people their ancestors were monster.

Before delving into the analysis conducted by JER of McCullough, I would like to turn to a topic that highlights some of the issues involved – the American Revolution.

YOUR COUNTRY IS ILLEGITIMATE

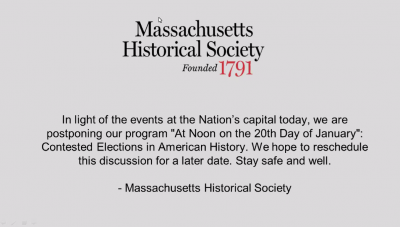

Lately we have heard a lot about our President being illegitimate. The loser of the election claims that the winner stole the election. This is an ongoing news story and may well be until the bicentennial of the election of 1824.

In the meantime, the legitimacy of the country itself is not at stake in the political machinations. Such considerations are not always true in the academic arena. It is not unusual for people to describe the United States as a country born in sin, perhaps, even two sins. Here one may observe the clash between wanting to alienate the general public versus wanting it to repent (and make amends).

Let me begin by going to the wayback machine for a post about a conference in 2013 called “The American Revolution Reborn.” The post is from my blog Rebirthing the American Revolution (November 29, 2016) citing another publication about it:

The interview on October 27 was by senior editor Samuel Hughes. It appears in the November/December issue of The Pennsylvania Gazette and follows.

The question from the audience bordered on the subversive. It came during “The American Revolution Reborn,” a 2013 conference organized by Michael Zuckerman C’61, emeritus professor of history, and Patrick Spero G’04 Gr’09, librarian and director of the American Philosophical Society, which hosted the event. (The conference also yielded a book of the same title, co-edited by Spero and Zuckerman and published last month by the University of Pennsylvania Press.)

“Somebody—clearly one of the non-academics—got up and said, ‘Look, all of you are full of nuance, full of contradictions of prevailing wisdom, but what do you really think? Was the Revolution a good thing or a bad thing?’” Zuckerman recalls. “He was sensing that the mood was overwhelmingly disenchanted, anti-heroic, anti-nation-building, and he was getting a distinctly negative, sour take on the Revolution. He wanted to know, ‘After all this, do you think we shouldn’t have done it?’”

Eventually Pulitzer Prize-winning Harvard historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich offered a response, but she “refused to give a bottom-line judgment—said it was the wrong kind of question—and left him hugely unhappy.”

The disagreement continued after the conference ended. Peter Feinman … reported on it extensively in his New York History Blog.

“Peter’s a thoughtful, critical guy but ultimately a high-powered patriot,” says Zuckerman. “He was saying [meaning not my actual words], ‘We’ve got to save the Revolution. It’s an inspirational thing—and you guys are not helping the cause.’ He took the side of the person who had asked the question and accused the historians of pussyfooting, and said that’s why they don’t have any clout and why we have nothing to say to people beyond our own cloister. And people weighed in—most of them attacking Peter, because they were scholars, but everybody was quite righteous.”

A smile plays across Zuckerman’s face. “It was a great brawl, with no resolution.”

Zuckerman anticipated some of the very issues and concerns expressed by the JER editors.

Here is what I actually wrote about that incident in a blog shortly after the conference:

The issue of leadership became a crucial one in the conference proceedings at least as far as I am concerned. Non-academic J.F. Gearhart asked one group of commentators if they thought the American Revolution was a good thing. Is the world a better place because the American Revolution occurred? The pained look on their silent faces spoke volumes. The anguished mental gymnastics of the three visibly uncomfortable academics was reminiscent of an American President coming up with “What is ‘is.’” Finally Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Harvard University, managed to say (and I am paraphrasing), “There were some good things which came out of the American Revolution and some bad things.” Gearhart pressed her to provide a “net-net” rendering on the Revolution. She declined to do so and laughingly noted that her students want her to do the same. (American Revolution Reborn: Missing New York July 10, 2013)

The conference, without meaning to, exposed two critical issues. First how did 19th-century Harvard American historian George Bancroft become 21st-century Harvard American historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich? When did elitist Americans change from being proud to be Americans to looking like deer frozen in the headlights when asked if the American Revolution was a good thing?

MICHAEL HATTEM I

As Michael Zuckerman reported, there was a response to my blog. Here is the comment by Michael D. Hattem, Associate Director of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute, a co-founder of “The Junto: A Group Blog on Early American History, author of Past and Prologue: Politics and Memory in the American Revolution, and currently working on Memory of ’76.

I think you misjudged her reaction, which was less that of a “deer caught in the headlights” than of mild bemusement. I also think that you have totally misinterpreted the audience’s reaction, as well. The vast majority of the audience, who were academics, did not have their breath taken away by Ulrich’s pause or her response. Rather, they were stunned that such a simplistic and impertinent question would even be asked at a conference like that and they were silent because they were waiting to see how Ulrich would address it. To her credit, she addressed it quite diplomatically and respectfully (more so than I suspect some in the room would have done). As she said, it was the kind of question that is asked by undergraduates with little to no experience with academic history as a discipline. The first thing an undergraduate learns in a college-level history class is to avoid such generalizations because they can never convey the actual complexity of history. Think of how simplistic and unfair the perception is that anyone who won’t come right and make such a generalized statement as “The American Revolution was good” as being “apologetic anti-American” or having an apologetically “anti-American” view of American history. Now you didn’t make that claim but you described the public perception and I would hope you could see why historians would react in that way to such an anti-historical and anachronistic perspective. I think many academic historians (especially of early America) acknowledge the need for historians to expand their audience among the general public but not by prostrating ourselves at the altar of American exceptionalism or nationalism.

Hattem did not write in boldface. Notice the putdowns of the questioner and me. Notice also how somehow saying the American Revolution is a net good becomes prostrating oneself at the altar of American exceptionalism or nationalism. Hattem continued:

If you want a sanitized, nationalist view of the Revolution and an endless stream of hagiographies of the founders, you can read McCullough, Ellis, Brookhiser and the dozens of others who have cashed in on the reading public’s desire for this Whiggish view. However, if you want to understand the Revolution more deeply outside of a small handful of elites and high politics and to understand how it affected groups of people differently, and how people on the ground actually experienced the Revolution, then you need the academics that were in that room at the APS, because they don’t choose topics or write books based on potential sales. Your instrumentalist and utilitarian view of history is completely at odds with the modern profession, the notion of which is reinforced by your expectations of the conference, which, like most academic conferences, wasn’t meant to provide a thorough narrative of the topic but specialized analyses of important themes. Historians are more concerned with what the Revolution meant to the people who lived through it and its immediate aftermath than what it means to people today. The former is history, the latter is politics. Either knowing or consciously shaping contemporary meanings of the Revolution is beyond the purview of historical inquiry for early American historians.

How does Hattem know that my expectations for the conference were for it to provide a thorough narrative of the topic? There is nothing in the conference schedule that even remotely suggests such an outcome. Since his current work is on the memory of the American Revolution over time and timed for the 250th anniversary of it, the idea that early American historians are not hoping to shape contemporary meanings of the American Revolution is suspect at best. I suggest his answer provides a casebook example of why academic historians may be regarded as elitists and of the challenge to be overcome to stop alienating the general public.

MICHAEL HATTEM II

In this regard, it is interesting to note the change in the tone by Hattem a mere eight years later. On January 27, 2021, He was the speaker in a virtual discussion at the American Philosophical Society (APS) on the topic of his book “Past and Prologue: Politics and Memory in the American Revolution. During the Q&A portion, I posed a question and he responded as posted on the APS website.

Q: I just received my copy of the current American Historical Review roundtable of Jill Lepore’s These Truths. This follows on the release of the 1776 Commission report by one president and cancellation by the incoming president. How do we go about creating a new national narrative today? (Peter Feinman)

A: I have thought about this question a lot in thinking about the contemporary relevance of my work and thinking about national memory [apparently no longer beyond the purview of early American historians]. My current project looks at the history of the memory of the Revolution in the 19th and 20th centuries and what I’ve found is that American history became politicized in a distinctly partisan way after 1800 and has been that way ever since. There has never been a time outside the window of the 1790s and early 1800s when there were not competing national narratives and memories. In other words, I do not think it is possible to create a new national narrative that could be widely accepted. Of course, one of the challenges there is that doing so would have to contend with the very powerful resilience of the Cold War-era memory that many American adults grew up with. All that said, I think we are currently in an important moment in the history of the memory of the American Revolution. Conflict over American history seems to ebb and flow along with the degree of political division in the country. Not unlike in the 1760s and 1770s, many Americans today are reconsidering the meaning and legacy of the Revolution. What is somewhat new is that many are calling for it to have no place in our collective civic and political cultures. I do not know if there is a way to create a national narrative with broad appeal in the present but I think that if it were possible it would require avoiding the two extremes we see so often currently of either seeing the Revolution as all good or all bad. What makes American history so interesting to me as a historian is its complexity and both of those extremes tend to flatten American history into two dimensions.

So he is thinking about it a lot … and providing a thoughtful answer. He recognizes the new phenomenon that there are Americans (Woke?) who think the American Revolution should have no place in our collective civic and political cultures. He rejects the view that the American Revolution should be seen as all good or all bad.

According to my notes, Hattem also was asked about what to do today given The New York Times Project 1619 and the (previous) White House 1776 Commission. He replied that he is not as indignant as he used to be [see his answer above from 2013]. He characterized both the 1619 and 1776 reports not as history but as memory construction. For Hattem, the American Revolution is part of the common inheritance for all Americans. We need to find a balance for this shared history which includes both horrible aspects and things which should be celebrated.

His answer reminds me a new development, not quite a trend, in these virtual presentations. I call it the 42 Minute Syndrome. After 42 minutes of being critical of the American Revolution, the speaker notes that there actually were some good things worth celebrating. For example, consider the virtual discussion held December 20, 2021, at the Wilson Center on Thirteen Clocks: How Race United the Colonies and Made the Declaration of Independence by Robert G. Parkinson. At the end of his opening remarks, Parkinson showed a slide saying:

REVOLUTIONARIES MADE MAJOR CHANGES TO COLONIAL POLITICS/LIFE

NO ARISTOCRACY, NO ESTABLISHED CHURCH, RELIANCE ON WRITTEN CONSTITUTIONS, TRANSFORMED MEANING OF REPRESENTATION AND CONSENT

THEY ALSO THREW AWAY THE CONCEPT OF MONARCHICAL SUBJECTHOOD & EMBRACED REPUBLICAN CITIZENSHIP

Parkinson noted what hadn’t happen before was any effort to make a new nation and new republican regime on a very different theory of citizenship. It sounds like he was saying these were good things even though his talk was not about them.

As Liz Covart summed up in her Ben Franklin’s World podcast discussion with Hattem on July 20, 2021, the new nation and political entity needed a new history to which all the different ethnicities could belong. Our familiar historical narrative originated in the effort to unite the populace into one people by creating a shared sense of the past. Exactly right.

Let me close with my closing words about the American Revolution Reborn conference

There is a difference between challenging America to be great and simply constantly condemning it for its shortcomings. Academics haven’t learned to speak the language of patriotism when criticizing America. They should champion the journey the Founding Fathers began, rather than only criticizing them for failing to meet their 21st century moral standards.

Yes, the American Revolution was a good thing, but we can’t rest on our laurels.

Yes the American Revolution was a good thing, but there is more that needs to be done.

Yes, the American Revolution was a good thing, and with your help the journey the Founding Fathers began can be renewed for the 21st century.