To understand historical Passover it must be placed in the context of Egyptian violence. Egyptologists who avoid the Exodus like the plague do not do this. Biblical scholars who know that there was no historical Passover do not do this either. They confine themselves to literary and/or ritual studies. However to understand historical Yahweh smites the Pharaoh’s men, one must understand the ideology and action of Pharaoh smites the enemy which Passover turns topsy turvy.

THE VIOLENCE OF A MA’AT-BASED WORLD

In her new book The Good Kings: Absolute Power in Ancient Egypt and the Modern World (Washington D.C., National Geographic, 2021), Egyptologist Kara Cooney refers to herself as a recovering Egyptologist from an abusive relationship. She does so in her opening chapter entitled “We Are all Pharaoh’s Groupies.” She states, “I work in a field of apologists who believe in an Egypt of truth, beauty, and power—and in many ways, I am still an adherent to my chosen faith.”

Now her eyes have been opened to the truth of ancient Egypt… or so she claims. One example she cites is the treatment of ma’at. Generally, Egyptologists understand this term positively. By this perception, Cooney is referring to the traditional view that posits ma’at as an expression of the best of Egyptian culture. It reflects understanding of the harmonious and ordered universe in contrast to the ever-present chaos which threatens it. After all, who wouldn’t favor the ordered sense of well-being of a society governed by the rules of ma’at to the disorganized world of chaos?

Cooney’s concern is for the always-overlooked flip side of ma’at in the real world. For Pharaoh, ma’at a tool of control. It is an authoritarian political ideology that justifies the power to oppress. In other words, it provides the ruler with carte blanche to act against those who disrupt ma’at as the forces of chaos. Specifically, smiting the enemy is “a necessary cruelty against those who harm the king’s people.” She sees Narmer’s Palette as celebrating the horrific subject matter while the moment of carnage itself is not displayed by the artisans. Cooney concludes that “ancient Egypt seemed better at hiding how cruel they could be, masking the viciousness with a morality that communicated a necessity for pain in search of what was right.”

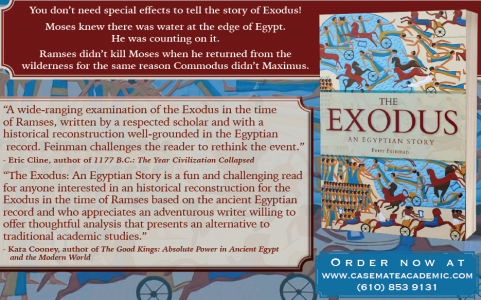

Cooney focuses on the practical application of the doctrine of ma’at by a ruling king. She observes that in “ancient Egypt the most violent rhetoric occurred in textual form and not in visual imagery.” She refers to the laudatory hymns and dramatic reenactments of battles. In my book, The Exodus: An Egyptian Story, I present the skull of Seqenenre as a striking example of the physical reality of “Pharaoh strikes the enemy.” The (racist) failure to recognize the skull as such derives from the refusal of Egyptologists to accept the kings of the 15th Dynasty as real Pharaohs.

Pharaoh himself does not of course do the smiting in Egypt. He has people to do the dirty deed. Cooney claims “the elites were the ones actually tasked with creating the blood and gore.” Without intending to, Cooney has identified the people who died in the historical Passover. The very people tasked by Pharaoh with the responsibility for smiting Moses and his supporters were the ones who were smited first instead.

Cooney concludes, “I, myself, have been co-opted, unable to recognize the propaganda that the ancient Egyptians were creating.” And all this is just chapter one. The rest of the book describes the violence perpetrated by leading royal figures—Khufu, Senwosret III, Akhnaton, Ramses II, and Piankhy. Her observations about Ramses II are particularly relevant to understanding the historical Exodus but outside the scope of this blog.

After this review of the savage brutal, and violent reigns of these kings, Cooney closes with some devastating comments about her field and her complicity in it.

We Egyptologists are members of the ancient Egyptian law-and-order party.

We Egyptologists often become apologists for a return to good kingship as the only thing that can save people from themselves.

In effect, the ancient Egyptians have hoodwinked us into believing that those periods of monarchical centralization were exactly the times when most ancient Egyptians themselves would have preferred to live … [because] the ideology of authoritarianism is seductive.

The Book of Gates incantation connects the patriarch’s [Pharaoh] use of violence to maintain a cosmic purpose.

She tells her grad students that Egyptology is dead. She herself is a “recovering Egyptologist. She acknowledges how the clever ideology of Egyptian Pharaohs worked on her mind and now recognizes how Egyptologists acquiesce to these ancient spin doctors. “[A]lmost all our scholarship is uncritically supportive of authoritarian policies. Unfortunately her book was published the same month as mine and I was unable to incorporate her comments especially on Ramses and the use of the term “Intermediate” by Egyptologists into it. Fortunately she was willing to write an endorsement of the book (see below).

STOCKHOLM SYNDROME

The very question of the existence of sanctioned murder in ancient Egyptian is a contentious one. Egyptologists who have studied this aspect of Egyptian life have expressed obstacles against this recognition that Egyptians ceremonially killed other Egyptians in public. The very idea touches a raw nerve – the sacrifice of humans is abhorrent so how could the civilized ancient Egyptians have done it?

… the more a topic touches on the scholars’ religious and political viewpoints, the less they are able or willing to evaluate the evidence as objectively as possible. The same is true of topics that touch on subjects to which we have strong emotional reactions (Kerry Muhlestein, Violence in the service of order: The religious framework for sanctioned killing in ancient Egypt, British Archaeological Reports International Series 2299, Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011).

Muhlestein is referring here not to the Exodus but to the perception among scholars that they, the cultured educated intellectuals of Western Civilization view themselves as the “cultural inheritors of Egypt.” They therefore put on “intellectual blinders” so as not to see their cultural ancestors engaged in such repellent behavior. The challenge then, according to Muhlestein, is to confront the historical reality that ancient Egypt engaged in public human sacrifice and to understand it in the Egyptian context. Laurel Bestock cautions that one should resist the temptation to interpret Egyptian imagery of violence as a direct report of actual events. The imagery is part of a larger ideologically driven narrative and not true to history (Violence and Power in Ancient Egypt: Images and Ideology before the New Kingdom (Routledge: New York, 2018).

However, even as Bestock cautions us she lays the groundwork for royal violence. The king is the figure of power. She declares that everyone else is, at least potentially, violently subject to him. The Egyptian values of kingship require a king to be violently physically dominant. The very right to smash heads was an exclusive power of the king. She wonders if smiting scenes were part of a royal ceremony, a drama that included named characters with set roles. Still, this definition of kingship certainly is suggestive that such violence occurred in the physical world and not just metaphorically or theatrically.

The smiting scenes demand careful scrutiny. Related to these scenes of sanctioned murder are the scenes of brutality and pain preceding the act. Mark Janzen refers to these scenes as the “iconography of humiliation.” The king communicated his dominance over foreign captives often through degrading imagery. The victims are shown in tortuous poses of humiliating helplessness (The Iconography of Humiliation: The Depiction and Treatment of Bound Foreigners in New Kingdom Egypt, The University of Memphis, PhD Thesis, 2013). Janzen has collected examples of these bound foreigners. We know that horror movies still draw today. The famous smiting scene from “Psycho” has become part of American mythology. But for the ancient Egyptian such images of cruel pain and horrible death were sanctioned … and by the king!

Instruction to Merikare (Middle Kingdom)

The hothead is an inciter of citizens,

He creates factions among the young;

If you find that citizens adhere to him,

Denounce him before the councilors,

Suppress [him], he is a rebel,

The talker is a troublemaker for the city,

Curb the multitude, suppress its heat,

… (Miriam Lichtheim, Egyptian Literature, Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1975).

These instructions to a king warn of the danger of the hotheaded rebel who can rouse the multitude. One presumes the warning to the king was offered because such situations had arisen in Egypt. Those occurrences are not likely to have been part of the official records of the king.

The focus then shifts to the punishment of disrupters of ma’at. After the text specifies what the king must do maintain ma’at, the Instructions states:

Thus will the land be well-ordered;

Except for the rebel whose plans are found out,

For god knows the treason plotters,

God smites the rebels in blood.

He who is silent toward violence diminishes the offerings.

God will attack the rebel for the sake of the temple,

He will be overcome for what he has done

One hardly needs to be an Egyptologist to recognize that in this world it is the king who is called upon in these Instructions to the king to be the one to implement the punishment against the rebels. To rebel against the king is to pay for it with your life.

I speculate that within the Egyptian context, Moses was the heated man. He was the hothead. He was the rebel. He was an inciter of citizens. He created factions. He violated ma’at. Therefore, one should expect Pharaoh to seek to respond to this heated man in accordance with Egyptian rules.

I speculate that Ramses correctly regarded Moses as an Apophis, a disrupter of ma’at. Therefore he decided to treat the hot headed rebel in accordance with Egyptian customs.

I speculate that Ramses intended to act at dawn of New Year against Moses and his followers when Sekhmet/Mut, the goddess of plagues and disease, acted as the destroyer of humanity. Moses knew this and did not wait to die before the face of Pharaoh (sunrise) would appear again.

Historical Passover where Yahweh smites Pharaoh’s tasked killers should be understood within this context of Pharaoh smites the enemy who disrupts ma’at.