Kirk Douglas died earlier this month. He, of course, is best known for his role as Spartacus. You may wonder what he has to do with local history. Douglas was born in 1916 in Amsterdam, NY. That city in the Mohawk Valley had an important role to play in the creation of this blog back in 2011…yes, it has been a long time!

In 2011, I led a Teacherhostel/Historyhostel in the Mohawk Valley. One of the stops was in Amsterdam. While there we visited the Walter Elwood Museum located along the banks of the Mohawk River. Originally it had been the home of Guy Johnson, nephew of William Johnson, one of the great unsung figures of colonial history. In 2009, the local museum had relocated to the Guy Johnson house. After touring the museum, we had dinner outdoors at a gazebo and listened to Peter Betz, the Fulton County historian.

A few weeks later, Hurricane Irene swept through the area. The gazebo is gone. The building is damaged. The museum has relocated. When I am in Amsterdam, I drive along Route 5 and sometimes stop to see the colonial ruin. According to the Montgomery County website, the fate of the building remains undetermined.

As a house, the building was not designed to be a museum. When we were there, parts of the museum were cluttered to say the least. However if you took the time to examine not the physical objects on the floor but the newspaper clippings on the wall, a whole new life opened up. Once upon a time, Amsterdam was an industrial powerhouse and the home of Mohawk Carpets. Museum Executive Director Ann Peconie’s grandmother had worked there. The workers in the factories were from many countries in Europe. The newspaper clippings attest the civic involvement of these different peoples. They had their churches, social clubs, and activities. It was not a “bowling alone” community that defines the isolation of people in communities today or the earplug people too engrossed in their gadgets to notice what is going on around them.

The Douglas obituary spoke of these times. Since he was Jewish, his father could not get a job in those mills. In his autobiography, Douglas refers to Amsterdam as a “WASP” town but that is incorrect unless he was lumping all Christians together.

But I want to direct your attention to the newspapers. These newspaper articles reflected the social fabric of the community. Many historical societies collect or have collected the local newspapers as part of the history of the community. What about today? What do you collect when the local newspaper is no more or is barely limping along? Does that mean there is no more local history? Or is it that we have to rethink how we collect it?

When I was growing up in New Rochelle, NY, we had a daily afternoon paper that was printed in town. I used to deliver it on my bike. Times have changed. The paper is no more having been absorbed by a larger and then larger entity. It is printed in New Jersey and then trucked to Westchester County for home delivery. The deadlines and transportation times mean night events that used to in the morning paper are no longer there. Forget about Superbowl or election results. It is as if they vanished into the void because the day following the next day they have become yesterday’s news. Too late to cover! Now suppose, your community doesn’t even have a paper!

What does all this mean for local news coverage and local history?

Last August, The New York Times had a special report supplement entitled “A Future without the Front Page.” The sole paragraph on the front page said:

What happens when the presses stop rolling? Who will tell the stories of touchdowns scored, heroes honored and neighbors lost? And who will hold mayors, police officers and school boards accountable? Local newspapers, starved for advertising and subscribers, are closing across America, leaving a void that the splintered threads of Facebook and Twitter may not be able to fill.

The first article was “Dying Gasp of a Local Newspaper: A Small-Town Pillar Ends a 121-Year Run…” According to the article, this paper joined roughly 2000 newspapers that have closed in the United States in the previous 15 years. That figure comes a study by the University of North Carolina entitled “The Expanding News Desert.”

The article then described what this individual community might look like when it joined that newspaper desert as its 121-year run ended.

No hometown paper to print the obituaries from the [local] Funeral Home. No place to chronicle the exploits of the beloved high school hockey teams. NO HISTORICAL RECORD FOR THE LITTLE TOWN MUSEUM, WHICH HAD CAREFULLY KEPT THE NEWSPAPERS IN BOXES GOING BACK TO 1897 {bold added].

And what about the next government scandal, the next school funding crisis? Who would be there? Who would tell?

These words expose the dual nature of the local newspaper. It reports on the social fabric and helps sustain it. Think of the pictures and articles of local school and organization events. It also exposes the social fabric. Kirk Douglas also wrote about the antisemitism he and his family experienced. I don’t know how often those events made the local paper.

So now we have counties with no local newspaper. Weekly papers that try to fill the void. I receive two. Papers that are part of chains with national news items that appear in all its local outlets. It used to be that a local community had a shared experience of reading the same newspaper every day. Does everyone in a community access the same website to keep up with local news? The local newspaper provided a tangible physical expression of the identity of a community and history museums and libraries kept a record of that identity.

On September 22, 2019, The New York Times published a followup article entitled “When a News Fold: ‘Our Community Does Not Know Itself.’” The article was a collection of responses to the supplement noted above. Here are the highlights from several of the respondents.

1. Town of 14,000 with no paper since 2006: “After years without a strong voice, our community does not know itself and has no idea of important local issues or how the area in changing…”

2. Newspaper closed in 2017 after 117 years: “Local stories about mayoral races, city and county council races, commissions, library activities, and school board decisions are all missing since our local weekly newspaper…went dark.”

3. “There is no way to learn about decisions of local governments, or even about the issues being raised.” Sydney, NY

4. School boards, town and village boards, county news, local news ⸺ it all disappeared. We were a check on government, on endless environmental and zoning hearings, on budgets that we often published in detail, on misdoings and good doings. There is now a void. No one took up the slack. Millbrook, NY

5. “[T]here is little oversight of local government and local business. The checks and balances afforded by this don’t exist, and it is only a matter of time before the potentially corrupt realize that they will be able to get away with corruption more easily.” Northampton, MA

6. “If you truly want to know what is going on, you need to attend every commission meeting and council meeting in person, and no one has the time for that.”

The issue is not one limited to small towns and villages. On December 22, 2019, City and StateNY published an article about New York City with the title “Is Local News Doomed: New York City’s biggest papers have slashed their metro shafts. Can Reporters Still Hold Politicians Accountable?” The article used the example of Congressional Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez appearing out of nowhere to win the primary to illustrate how the major New York City newspapers have lost contact with the local world. The newspapers covered were The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Daily News. The newspapers still exist but the staff covering local news has been reduced.

There have been some efforts to stem the tide. For example, Report for America, created the GroundTruth Project. It operates on the basis of the Peace Corps to fund reporters in existing newspaper operations. It deployed 50 people last year and intends to raise the number to 250 this year. It asks news organizations, including nonprofits, to identify civically important gaps in their news coverage, such as health care, the environment, schools, criminal justice or whole regions or communities, for which they would use a Report for America reporter. These young journalists commit one or two years to these communities because they believe local journalism is a public service, just as much as being a teacher or a nurse. By being on the ground, and present, they let the community see reporters as their advocates, in it for the right reasons [and are not the enemies of the people].

Sometimes even a single individual without funding can make a difference. Carl Butz, 71 years old and retired, is seeking to save The Mountain Messenger from extinction (NYT, 2/210/20, print). California’s oldest weekly paper was founded in 1853. The newspaper “was something we need in order to know ourselves.” The paper in a repository of the county’s history.

What is the social fabric of the local community? Putting aside sociological jargon, there are several specific institutions and organizations that contribute to connecting people where we live to each other – the local schools, the local library, the local newspaper, the local history museum, and the local churches are integral to the development of a sense of place, a sense of belonging, a sense of community.

Amsterdam still has The Recorder but I don’t know if anyone is clipping articles or not. And the community that Kirk Douglas knew has vanished.

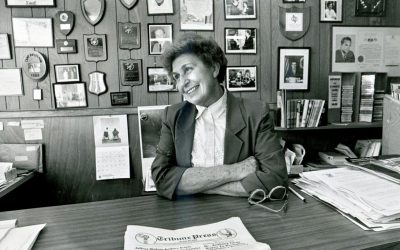

Perhaps greatest example of local history and the local newspaper telling story occurred with Veda Ponikvar and the Chisholm Tribune Press, a weekly newspaper in Minnesota first published on July 2, 1947. “Who?” you might ask is she. Ponikvar is best known for an editorial she wrote in 1965 after the death of a beloved local doctor:

As the community grew, Doc became an integral part of the population. There were good years and lean ones. There were times when children could not afford eyeglasses, or milk, or clothing because of the economic upheavals, strikes and depressions. Yet no child was ever denied these essentials, because in the background, there was a benevolent, understanding Doctor Graham. Without a word, without any fanfare or publicity, the glasses or the milk, or the ticket to the ball game found their way into the child’s pocket.

You may recognize those words. They made it into a book when an author conducted research at the local paper and it was included when the book became a movie.

In the mid-western town of Chisholm, Minnesota, the townsfolk were celebrating their 100th year Centennial (1888-1988). To locate “Moonlight,” they [Kevin Costner and James Earl Jones] entered the main street office of the Chisholm Tribune Press, and inquired of the paper’s publisher Veda Ponikvar (played by Anne Seymour) for the whereabouts of the ex-baseball player….From “Doc’s” death folder in a back-room, the publisher held up an old newspaper clipping about “The Passing of a Legend”

Field of Dreams contains perhaps the most famous newspaper file in cinematic history. The musical Hamilton asks who will tell the story. How will we tell it when there are no local newspapers to record it?