Angolans are in the news. Recently there has been a surge in migrants from Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo. After a decade of hardly any migration from these countries, suddenly the numbers have increased specifically to Portland, Maine and to San Antonio, Texas. The surge has overwhelmed the communities. Unlike the Central American migrants, the Central African migrants are less likely to have relatives already in the country to whom they can turn for assistance.

The Angolan/Congolese story in America dates back to the 1600s including to the very Town of Rye where I live. It is a story I recently have been investigating. With all the attention on the figure of Christopher Columbus, it is easy to overlook Prince Henry the Navigator (1394-1460) of Portugal. He initiated voyages along the coast of Africa. Although the Portuguese did not reach Angola during his lifetime, by the end of 16th century, they had and had begun the slave trade there. The primary exchange was with the Portuguese colony of Brazil. There were no British colonies in the future United States yet.

It should also be noted that Catholic Portugal converted the Angolans and Congolese to Catholicism. Exactly what Catholicism meant to them is another matter but we need to recognize that Africans had been exposed to European culture prior to their arrival here. Of course, to the British Protestants, Catholicism was practically a heathen religion anyway. To understand this period, we should keep in mind the religious wars that dominated Europe: the Thirty-Years War (1618-1648) and the English Civil Wars of the 1640s and 1650s which witnessed the rise of Cromwell and the execution of Charles I. These events are part of the reason why scholars use the term Atlantic Studies now. It encompasses a greater area than a more limited focus on the 13 colonies themselves.

The intersection of this African world and New York is covered in the chapter “Encounters: Slavery and the Philipse Family, 1680-1751” by Dennis J. Maika, The New Netherlands Institute, in Dutch New York: The Roots of Hudson Valley Culture, ed. Roger Panetta. Dennis prefers to use the designation “Kongolese” stating that a majority of Angolans were Kongolese. Since the legal documents I will cite calls the people “Angolans,” I will use that term.

During the 1600s, these people lived primarily in agricultural societies. Those who lived along the Kongo River became river traders and were in contact with other peoples. Even without the arrival of the Europeans, these African peoples fought with each other and took captives. These captives can be considered slaves although it was not slavery in the American or Brazilian sense. Beginning in 1640s, the coastal town of Soyo became the point of departure from Africa for these captives to the newcomers who had arrived on the scene. The Dutch and English traders vied for this trade. The result was an accelerated effort by the locals [indigenous people] to procure an ever increasing number of captives to meet the demand.

In describing this situation, Maika writes:

Kongolese captives were held in high regard by European slave traders and buyers because of specific cultural traits that were valued by slaveowners.

In a footnote, he elaborates on this point. The specific traits the Angolans were perceived to have were that they were docile, comely, not strong, predisposed towards mechanics, but prone to run away. These characteristics made them attractive for working the sugar plantations in Barbados…after all, where were they going to run away to?

Frederick Philipse of New York City and the Hudson Valley decided to join this network. His first foray into the slave trade occurred in 1685. The New York connection was not part of the original plan. His ship the Charles was supposed to discharge its full complement of human cargo in Barbados. The initial number of captives at Soyo of 146 had decreased to 105 by the time the Charles arrived in Barbados. They were not all suited for plantation work and nine of them remained on board for the voyage to New York as “refuse cargo,” no one wanted. Instead the captain of ship brought them to New York where they landed around Rye. Of the nine, eight were marched across Westchester and helped build the Upper Mills in what is now Philipsburg Manor in Sleepy Hollow. These Angolans were there at the beginning of construction. Maika considers them ethnically coherent core of the community perhaps including a female later named Old Susan. One might add that perhaps the perceived skill in mechanics contributed to their becoming mill operators, a skilled position at the manor.

One might ask how is that there is any information about this voyage. It’s not as if such detailed records were maintained comparable to what we consider routine today. A person geographically knowledgeable might inquire why did the Charles dock in Rye on the Long Island Sound on the east side of Westchester County instead of sailing to the Upper Mills on the Hudson River on the west side of Westchester County. Why the forced march across the county at its widest point?

Researching this question took a little doing. I became interested in this question through my participation in a working group of the Westchester County African Advisory Board tasked with recognizing the 400 year anniversary of slavery in the British colonies, the subject of a previous blog (Slavery Quadricentennial: The 400 Years of African-American History Commission). My focus in the committee has been on the New York story and not the Virginia or Texas stories. Our story of the ending of slavery was July 4, 1827. But what about its beginning at least in Westchester?

Slavery in New York City seems to have begun immediately after the Dutch purchase of the island in 1626. The connection with Angola and the Congo originates at that time based on the names of people sold. New York was beginning the process of becoming the second-largest slave trading market in the British colonies. Now there is a history marker on Wall Street to acknowledge that fact. These sales tended to involve individuals and whether any of them ended up in Westchester is difficult to determine.

The big event in Westchester was the Charles in 1685. I began to research the event with the assistance of Patrick Raferty, Westchester county Historical Society, Sheri Jordan, Rye Historical Society, Michael Lord, Philipsburg Manor, and Dennis Maika, New Netherlands Institute. My readings involved tertiary, secondary, and primary sources. It took a while to go from people citing each other to drill down to the original data.

The data makes clear why the Charles was in Rye and why it was remembered. There were not supposed to be any people for sale on the ship in the first place. The Upper Mills was not yet built in the second place. And New York City resident Frederick Philipse did not want his cargo ship to dock in the city in the third place. If it had, he would have had to PAY TAXES. His subterfuge did not work. He was charged with smuggling “8 Negro slaves, 80 lbs. of pepper, 40 yards of cloth, 12 pewter dishes, 1 sheet cable, I hawser, 2 great guns, 2 new sails, and other goods” according to the court records. [To get this information I had to rescue a book from the loading dock at Columbia Law School before it was shipped to New Jersey!] The court record lists the 11 jurors and the verdict rendered was not guilty, August 4, 1685. Apparently it pays to be rich.

The details about the Charles come from a deposition taken on July 21, 1685 and filed separately from the court record of the verdict.

Now what? Efforts to locate exactly where the Charles docked were fruitless. It was a surreptitious act not repeated. I wanted to know where so I could recommend that a history marker be placed there – from 1685 to the confiscation of Loyalist Philipse land in the 1780s marked a century of slavery of Philipsburg Manor.

Since the exact location cannot be determined, I chose a site: the boardwalk at Playland Beach where Tom Hanks became Big. Instead of placing a sign at some inlet that no one can access and may not be the actual site why not place it where it will be seen by many. The Rye Historical Society and the Westchester County Executive agreed so that is what I am trying to do.

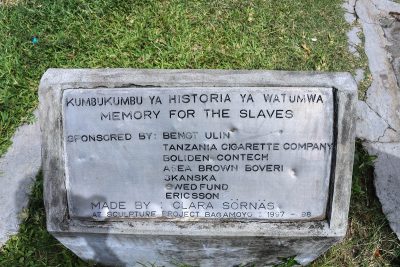

But a New York State facsimile history marker such as the Pomeroy Foundation funds is a pretty simple, sign. Maybe more could be done. Maybe there should be an image of some kind depicting the moment. Vinnie Bagwell, a member of our committee, is a sculptor working on the “Enslaved Africans Rain Garden” project to be unveiled in Yonkers this fall depicting manumitted slaves from Philipsburg Manor. When she commented on doing something more artistic, it triggered a thought in me: why not create a sculpture of the 8 Angolans coming ashore in chains in Rye possibly including Old Susan, a name known from the Philipse’s records. While I was basking in the glow of having this idea to create a visually powerful expression of slavery that could serve as an educational resource and tourist destination site, I learned that Zanzibar already had done something similar. The image at the beginning of this post shows five people about to depart their homeland; the proposed Rye sculpture would portray their arrival in their new homeland.

So that is my new goal. To get a history marker of the event in 1685. To get a sculpture of the event of the 8 Angolans. To invite the Angolan and Congo ambassadors to the dedication. To get 16 high schools in the area to each march one mile from Rye to Sleepy Hollow. To have someone write a play about Old Susan. Can all that be done? I do not know but it’s worth the effort.

P.S. I am not a Philipse. I am not Angolan. I am not Dutch. I am not African. I am a resident of the Town of Rye. That means the stories of my community are now part of my heritage just as you do not need to be a son or daughter of the American Revolution to celebrate July 4 as the birthday of your country.