The American Historical Association (AHA) held its annual conference on January 5-8, 2012, in Chicago. One of the non-academic issues it addressed was the employment situation in the history profession. The impetus for the last-minute session at the conference on the subject was an essay by Jesse Lemisch, Professor Emeritus of History at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice of the City University of New York titled “History is Worth Fighting For, But Where is the AHA?“.

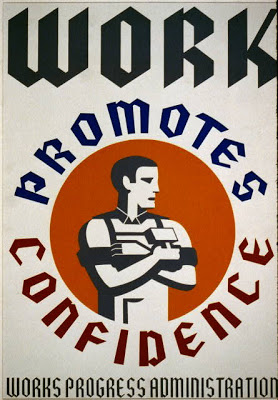

As the inflammatory title suggests, Lemisch was spoiling for a fight. His targets were Anthony T. Grafton and Jim Grossman, respectively president and executive director of the AHA. Their solution, “No More Plan B: A Very Modest Proposal for Graduate Programs in History” had been published in the October 2011 issue of Perspectives on History. Lemisch’s withering response was: “What they propose is indeed too modest, almost tragically so. What we need is not cutbacks and accommodations but rather vastly expanded funding for higher education, plus a program for historians like the New Deal Federal Writers’ Project, which produced so much of value, including the slave narrative collection and the 48 volumes of the American Guide Series to the states.”

Lemisch’s own view of history’s place undoubtedly will resonate with readers here, but I wonder how many Americans accept these precepts: “What’s lost in this is the high value that we place on history and a complex that connects history to civilization itself. History is worth fighting for, and its importance goes far beyond the current vogue for saleable skills and narrow vocational justifications for education.” He ended his blog which was written at the time of Occupy Wall Street with: “It appears that those druggies, drummers, sex addicts and student debtors down there in Zuccotti Square are doing more for civilization, history and education than is the AHA. It’s time for the AHA to catch up with them, and start fighting for history.” One may question whether that comparison has more to do with Lemisch feeling good in writing a zinger than in gaining support from the AHA on his proposal.

The AHA did have a session entitled “Did We Go Wrong? The Past and Prospects of the History Profession.” James Axtell, of William and Mary, opened the session by wondering whether professors are “just creating ego-driven clones of ourselves in our PhD programs.” AHA deputy director and all-around statistics guru Robert Townsend, presented evidence outlining the explosive growth in PhD-granting institutions over the past forty years, especially in public, usually regional, universities. He argued these programs fulfill a critical need at the local level that national programs like Harvard and Yale simply do not.

Thomas Bender noted that many history students including in public history have no intention of pursuing careers in history. He argued that humanities PhDs in general, and history PhDs in particular, are sought ought by consulting firms like McKinsey and Deloitte for their humanistic, as opposed to strictly quantitative, analytical and research skills. Thus Professor Newt Gingrich’s seven-figure fee for historical work at Freddie Mac may be the wave of the future! Closer to home, Bender’s own daughter, a classics student, received a job offer from Silicon Valley. So perhaps history professors instead of trying to produce clones of themselves should work with the business school and law school to develop training in more realistic career paths.

According to a commentator, the discussion became more heated in the follow-up session “Jobs for Historians: Addressing the Crisis from the Demand Side,” created in response to the Lemisch essay. He felt the teeny-tiny pragmatic changes within the field being proposed were the equivalent of “rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.”[Note: the centennial is this April so expect a lot of Titanic references.] Other participants were less sanguine about the prospects and longevity of a government-funded program for historians. Lynn Hunt, UCLA, questioned the public support for a WPA program for academics noting, “The Left has been more influential among AHA members than voters as a whole.”

The various comments about public history as a possible career option attests the traditional second-place status of public historians in the field of history to the historians who do research and train graduate students to replace them. This also leads to the distinction between popular history and scholarly history.

The commentator covering the event for HNN concluded with: “Considering that the room was packed nearly to the gills, the comments from the audience were a true highlight. Indeed, Grafton tried vainly to keep the session going after the allotted time expired, but alas, the room was reserved for another panel. And indeed, the comments were wide-ranging, from a former department chair who decried the bevy of unqualified applicants he waded through while making his latest hire, to an adjunct who, if anything, felt Lemisch’s proposals didn’t go far enough.”

Obviously the story is far from over. Perhaps the OAH conference in April in Milwaukee will provided another chapter to this tale.

On a local note, one should realize that although New York State requires historians at all municipal levels there are no requirements regarding the education and training of such people nor is there funding sufficient for the jobholders to make a living (and pay off student loans) unless the job is part of a larger job such as managing the archives. Is it even possible to imagine a world where town, village, city, and county historians routinely were full-time jobs attractive to history professionals? How about high school history teachers having a masters in history? The fact that these two suggestions are laughable reflects on the true value we the people place on history as part of the way to develop a sense of place, a sense of belonging, a sense of community as citizens of this country.