Previous posts here have addressed issues raised at the annual conference of the American Historical Association (AHA) on of the lack of history jobs and the lack of history interest by the press. Related to that, a discussion on a history list last summer focused on the disconnect between the world of academic historians and the general public under the heading of “Scholarly versus Popular History.” The following submission by Lance R. Blyth, University of New Mexico (7/19/11) deserves attention:

“As someone who sits in the borderlands between academic and popular history, I do believe there is a critical difference between the two: their intended audiences. Scholarly or academic historians write history for other academic historians and so need to exhibit a deep historiographical knowledge and engage with the issues and debates within their fields. Popular historians write history for the educated general readership and while they may be aware of the debates, issues, and historiography (many, unfortunately are not), they do not have to display this for their readers to see. Indeed, their readers aren’t looking for it, don’t expect it, and may well become annoyed when they see it!”

As an example of the difference between scholarly and popular history, Blyth cited a recent review by Gordon Wood, a well-known scholarly historian of Ron Chernow’s, a well-known popular historian, biography of George Washington:

“Chernow is an outstanding member of the new breed of popular historians who dominate narrative history-writing in the United States today. Independent scholars such as Chernow, David McCullough, Walter Isaacson, Jon Meacham, Thomas Fleming, Stacy Schiff, Richard Brookhiser, David O. Stewart, James Grant, Eric Jay Dolin, Barnet Schecter, and others do not have Ph.D.s in history and possess no academic appointment. They are not engaged in the conversations and debates that academic historians have with one another, and they write their history not for academic historians but for educated general readers interested in history. This gap between popular and academic historians has probably existed since the beginning of scientific history-writing at the end of the nineteenth century, but it has considerably widened over the past half-century or so. During the 1950s academic historians with Ph.D.s and university appointments, such as Richard Hofstadter, Samuel Eliot Morison, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Allan Nevins, Eric F. Goldman, Daniel Boorstin, and C. Vann Woodward, wrote simultaneously for both their fellow academicians and educated general readers.

This is normally no longer possible. Academic historians now write almost exclusively for one another and focus on the issues and debates within the discipline. Their limited readership – many history monographs sell fewer than a thousand copies – is not due principally to poor writing, as is usually thought; it is due instead to the kinds of specialized problems these monographs are trying to solve. Since, like papers in physics or chemistry, these books focus on narrow subjects and build upon one another, their writers usually presume that readers will have read the earlier books on the same subject; that is, they will possess some prior specialized knowledge that will enable them to participate in the conversations and debates that historians have among themselves. This is why most historical monographs are often difficult for general readers to read; new or innocent readers often have to educate themselves in the historiography of the subject before they can begin to make sense of many of these monographs.

So advising academic historians that they have to write more stimulating prose if they want to enlarge their readership misses the point. It is not heavy and difficult prose that limits their readers; it is rather the specialized subjects they choose to write about and their conception of their readership as fellow historians engaged in an accumulative science.

The problem at present is that the monographs have become so numerous and so refined and so specialized that most academic historians have tended to throw up their hands at the possibility of synthesizing all these studies, of bringing them together in comprehensive narratives. Thus the academics have generally left narrative history-writing to the nonacademic historians and independent scholars who unfortunately often write without much concern for or much knowledge of the extensive monographic literature that exists.”

Another contributor to the list, apparently not an academic since no such title was included in the email, asked:

“How does one get a more general readership interested in the sort of history that goes into a SHEAR [Society for Historians of the Early American Republic] conference or the JER [Journal of the Early Republic], [or NYSHA, one might add] or history that is solidly built on such a foundation?”

Towards that end a notice went out about the AHA 2013 conference which has the theme “Lives, Places, Stories” in accordance with the AHA’s new president William Cronon’s call for historians to think about how the craft can reach new and wider audiences. A contributor who specializes in the Gilded and Progressive Ages subsequently solicited participants for a panel he was proposing to fulfill this request. He wrote: “I am hoping to put together a panel that explores biography and microhistory as a mode of research and writing that can advance scholarship.” That microhistory sounds a lot like what many non-academic public historians already do. For example Rich Borkow, the Dobbs Ferry historian who has participated in a number of IHARE programs both as student and presenter, wrote George Washington’s Westchester Gamble: The Encampment on the Hudson and the Trapping of Cornwallis; many public historians have written books about their communities which have been published by local presses without their necessarily being academic historians or holding any history degree yet alone a graduate one.

As Borkow’s book points out, just because an event occurred locally, doesn’t mean it doesn’t have national significance. Conversely scholarly historians researching the Gilded Age or the Progressive Era, to use the example above, have much to learn from a “microhistory” in any number of communities in New York State which have stories to tell precisely about those periods. How do we go from the anecdotal telling of stories to the creation of an historical narrative or thematic analysis that incorporates the local into the national? If New York schools are teaching the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, why can’t it be done through local examples? Gilded Age mansions have a story to tell within the context of the national narrative, but how do we bring together the scholarly historians, the public historians, the teachers, and the historical sites to tell that story in an exciting and informative way that provides the participant both with a sense of place in own’s community while also being part of national story? How can public and independent historians work more closely with academic historians without necessarily getting an advanced degree? Perhaps these are questions which can be discussed at our history conferences and as the new common-core social studies curriculum is developed. Or perhaps not.

Peter Feinman founder and president of the Institute of History, Archaeology, and Education, a non-profit organization which provides enrichment programs for schools, professional development program for teachers, public programs including leading Historyhostels and Teacherhostels to the historic sites in the state, promotes county history conferences and the more effective use of New York State Heritage Weekend and the Ramble.

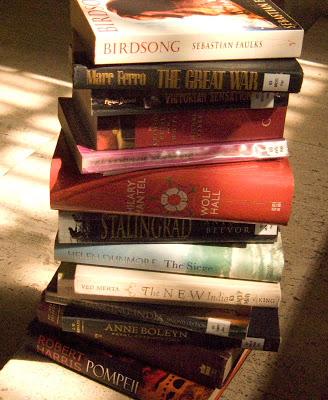

Photo courtesy Novel Approaches: From Academic History to Historical Fiction.

Thanks for making me feel like the caveman in the Geico commercial.