It is with deep regret and heavy heart that I have the onerous task to inform you that once again the world has come to an end. The passing of our beloved planet marks the third time in this still young century when we endured this ignominious ending to our long history.

First came the secular Y2K ending, then the Christian rapture in 2011, and now the Mayan recycling of 2012. The ending of the world has become as frequent as the storms of the century. We scarcely have time to catch our breath before once again the world will fall over its cliff into an abyss from which it can never recover.

For the historian, these predictions of the end of the world provide important insight into the workings of the human mind. One notices that rarely do these prophecies of calamity derive from visions. Those who so loudly claim that the end is near tend not claim receiving some divine knowledge. Instead they seek to overwhelm us with facts based on extended research with primary source documents. People With great vigor and incredible patience, people proceed step by step with the data to construct a narrative that logically proves that yes, in fact, the world is coming to an end. These purveyors of doom are secure in the knowledge that scientific thinking has been brought to bear. They conclusively prove to anyone who will follow their logic that it is time to cash in the those IRAs and eat, drink, and merry.

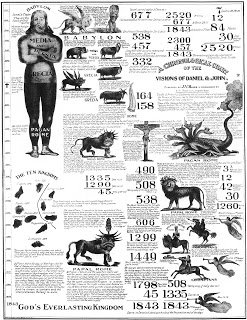

In America, one prediction for the end of the world began in Washington County, New York with William Miller. In front of me are two broadsides boldly proclaiming his message. The first big headline forecasts the end of the world in 1843. The second and more famous followed the failure of the first – recalculations set the day of doom to October 22, 1844. That pronouncement brought people out in droves who waited quite religiously all through the night for the event which never occurred. The day would be remembered as the “Great Disappointment” and if there had been late-night comics then those believers would have been the butt of national ridicule, which they actually were in 1844.

Miller’s epiphany occurred not from a vision but from an experience. Miller was a soldier in the War of 1812 who fought at Plattsburgh. For him the first 9/11 in American history proved to be a turning point in his personal life as he despaired for a hopelessly corrupt humanity. On the Sunday following the two-year anniversary of the September 11, 1814 battle, Miller became emotionally overcome. He began a two-year study of scripture in hopes of reconciling rationalism and religion. By 1818 he had worked out the math through his self-guided study of the biblical text and concluded that the end was near, just 25 years away. He didn’t go public with this information until 1831 and continued to fine-tune his calculations until arriving, under some pressure to be precise, at the date of October 22, 1844.

Reason not vision powered his analysis. That effort didn’t stop in 1844. In the decades that followed, small-print articles of extraordinary length were cranked out with unbelievable speed citing the same verses from the same biblical texts to arrive at different answers. All these musings about the pending end of the world led to the first meeting of the American Bible and Prophetic Conference held, of course, in New York. Premillennialists have the same human need to gather periodically with colleagues as any one else and the place they eventually chose to meet annually became known as the Niagara (Canada) Bible Conferences. These conferences produced the Niagara Creed which became a forerunner to The Fundamentals printed in the early 20th century which gave rise, in part, to fundamentalism. The belief in the end of the world really rose to new heights in the war to end all wars, the centennial of which will shortly be ignored in New York.

In the meantime while all this talk of boarding the ark before it was too late went on, another approach, took root here in New York. John Heyl Vincent, the great Methodist educator of the second half of the 19th century (with family background in New Rochelle), launched a series of education programs more in the style of Benjamin Franklin than the premillennial institutes and conferences. These programs went under the name of Chautauqua which continues to operate in New York to this very day. Through education people would improve themselves and therefore the world around them, a more traditional American view. This middle-class effort based on an old Methodist camp-meeting site in New York became a national phenomenon. If people couldn’t come to Chautauqua then Chautauqua would go to them through the Uniform Sunday School curriculum for all Protestant Sunday schools in America and the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle (CLSC) book list years before Readers Digest and Oprah.

Chautauqua and Niagara (Canada) offer two contrasting perspectives on the end of the world. New York’s Path through History should highlight not only Chautauqua’s role in the late 19th century and early 20th century with its summer institute, reading list, and circuit Chautauquas that plied the heartland of America, but for its continuing importance today as a reminder that the need for learning never ceases and that an engaged mind is still the best path to a better tomorrow. When all it said and done, when it comes to the end of the world, the great champion from New York is not William Miller, Joseph Smith, the Oneida Perfectionists of John Humphreys Noyes, or the Shaker Society (aka the Millennial Church). Instead the greatest purveyor of the end of world turns out to be someone troubled by the bomb and fearful that the wrong button would be pushed who left us his eternal legacy.

Happy New Year – there will be many more to come.

Illustration: Millerite prophetic time chart from 1843, published by J. V. Himes. Courtesy Wikipedia.

Peter Feinman founder and president of the Institute of History, Archaeology, and Education, a non-profit organization which provides enrichment programs for schools, professional development program for teachers, public programs including leading Historyhostels and Teacherhostels to the historic sites in the state, promotes county history conferences, the development of Paths through History, and a Common Core Curriculum that includes local and state history.