Scholars divide time into periods in an effort to make history comprehensible, but when to draw the diving line can be problematical and historians often disagree where one period ends and another begins.

For the birth of the nation, I am using the end of the colonial period, roughly from the French and Indian War to the end of the War of 1812. The colonial era for me was the time of the settlement of the 13 colonies which would become the United States. That process began in Jamestown and ended approximately 130 years later in Georgia. Up until then individual colonies, notably New York, Massachusetts / New England, and Virginia, dominate the curriculum, scholarship, and tourism, with only passing references to the Quakers in Pennsylvania and the Dutch in New York.

These separate stories shifted with two pivotal events. First, the Great Awakening with George Whitefield, a religious phenomenon that swept over the colonies and ran roughshod over the carefully delineated borders of parishes and churches. This is considered America’s first “national” event. The second was the French and Indian War which transcended the borders of individual colonies and now signals a continental identity. Good, proud, loyal subjects of the British king fought against France and the papacy. George Washington – a large physically-powerful male astride a horse dominating a situation by his presence – emerged as the first action hero in American history.

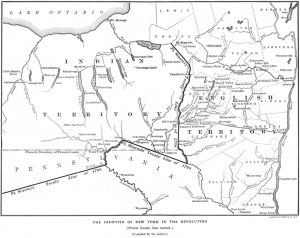

In the New York, the French and Indian War occurred mostly upstate and on the Canadian border, a border Americans frequently tried to changed. The French were displaced by the British, just as the British had previously displaced the Dutch in New Netherland. Only a few decades earlier, Niagara had been a mythical place of awesome power and beauty beyond believability; now it was the site of confrontation of global powers. Forts Niagara, Oswego, William Henry, and Carillon/Ticonderoga, settlements like Hoosick and German Flats, and the Lake George region, all became part of the American story. Initial French victories soon gave way to British triumphs and greater support from the divided Iroquois. Some of the same sites and areas would play host to American Revolution and War of 1812 battles. The British gained valuable field experience, and knowledge about the terrain of these future battlegrounds during the war.

Massachusetts garners the bulk of attention for the period between the war we fought alongside the British, and the one we fought against them. The Stamp Act, the Boston Massacre, and the Boston Tea Party with continental meetings in Philadelphia remain the most noteworthy items. However, during this period a signature event occurred in New York as well. In a convocation of thousands in the fall of 1768, native people and representatives of the crown gathered at Fort Stanwix to redraw the boundary set by the 1763 Royal Proclamation. Scholar William J. Campbell called it “one of the greatest spectacles of diplomacy in colonial America.”

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix recast the boundaries between colonists and native people from Florida to the Great Lakes. It culminated a series of conferences and meetings, beginning in 1765, at Johnson Hall that considered the interior of the continent. Vast areas in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Ohio were part of the debate. The boundaries of a huge expanse of America was negotiated in upstate New York. Whatever loyalty Johnson had to the Iroquois was overcome by the power of land hungry speculators and settlers. The resulting treaty has been called one of the worst in British-Indian relations, one that heralded rather than impeded land fever. One the biggest land owners had been Johnson himself, who owned 50,000 acres.

In the real world, what would you have done if you were William Johnson? The colonial era was ending. The Dutch had been displaced. The French had been displaced. The Yanks were coming. Here is an excellent case study for the New York State curriculum.

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix presents a comparatively unknown event and a springboard for thinking about New York at the cusp of the colonial era and the birth of the nation. It helped set the stage for the wars to come, and the place of New York and the United States in world history.

Illustration: Part of the 1768 Fort Stanwix Treaty line.

Had Johnson lived longer he may have been our “George Washington,” or maybe theirs…