In some ways, Columbus Day is Ground Zero for the culture wars. Here is where the two white sides square off in the battle for power in America. Each white side claims right is on its side and as always the American Indians are caught in the middle. This blog is a continuation of a series on the white people conflict between Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples’ Day. For those who are keeping track, the previous related blogs are listed at the conclusion of this one.

In this post, I want to focus on the words of James Axtell who in 1992 was a history professor at the College of William and Mary and the chair of the American Historical Association’s Columbus Quincentenary Committee. In that capacity, he authored an article “Columbian Encounters: Beyond 1992,” published in the William and Mary Quarterly in 1992.

Axtell began the article optimistically. He expressed his hope that the Columbus Quincentenary would be more successful than the Bicentennial had been in realizing its educational potential. He identified various reasons why it would make a deeper public and pedagogical impact than the 1776 anniversary celebration had. Since then, of course, the intensity of the culture wars has grown.

In his analysis, Axtell introduces a critical term that unfortunately has never caught on. He recommends the word “Encounter” as the theme of the Quincentenary. He does so “although natives. Critics, and activists may not approve the idea, encounters are morally neutral: the term does not prejudge the nature of the contact or its outcome.” Naturally I was quite pleased to read about his use of this term since without being aware of this article and more familiar with the term from the movie “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” I had used that very word in my own blog in 2017 appropriately entitled Columbus Day: Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

The bulk of the Axtell’s article recounts his impressive familiarity with all articles, books, conferences, exhibits, and manner of scholarship related to the Quincentenary. He is pleasantly surprised that the quality of Quincentenary scholarship is so high. Now what, he asks at the end? What should be done to keep the momentum going beyond 1992? He wrote:

My survey of the Columbian Encounter field suggests the following prescriptions:

(1) We should focus on Columbus as a man of extraordinary perseverance, skill, and luck but a man nonetheless – flawed like all men. Rather than caricaturing him as an oversized hero or villain we should see him in full perspective, pre- and post-1492, and measure him primarily against the men, ideas, and mores of his own time.

(2) We should pay more attention to Europe on the eve of colonization as the locus of experience, goals, and methods for the American incursions.

(3) We should pay much more attention to precontact America: its complexity, variety, demography, and deep reservoirs of human experience. We should make greater efforts to really hear native voices from the past and in the present, not only for Clio’s sake but to advance our own necessary and liberating education in otherness.

(4) In our writing and teaching of colonial history, we should rescue the sixteenth century from undeserved neglect. Without it, we have no hope of making sense of its more familiar sequel.

(5) We must learn to do justice to Hispanic America, first by ridding ourselves of the Black Legend and then by pursuing its history beyond the short conquest phase into the less sanguinary settlement period of city building, imperial bureaucracy, sugar plantations, cattle ranches, and widespread acculturation. We should also do a better job of integrating the Spanish borderlands with the histories of North America and the United States.

(6) By the same token, we should incorporate the history of the Caribbean, where Europe often fought its intercolonial wars before landing on North American soil, because the sugar islands were so valuable to the mother countries.

(7) We should continue to pay attention to the role of disease and biological imperialism in the conquest and depopulation of the Americas. But we should refine our estimates of mortality to accord with the best available evidence and with common sense.

(8) While well-publicized historical anniversaries occasions for them, we should curb the temptation worse, predetermined moral judgments on the enough after we have done our homework thoroughly.

(9) Whenever possible, we should resort to the insights and viewpoints of other disciplines, such as anthropology, archaeology, ethnohistory, cartography, historical geography, and colonial discourse. Even the historical fiction of Latin American novelists such Abel Posse, Alejo Carpentier, and Antonio Benitez-Rojo stretches the imaginative limits of our understanding of the Spanish and Indian heritages of that first, vast, other America.

(10) On a similar tack, we should employ whenever possible a comparative perspective on the American Encounter-comparing French, Spanish, English, Dutch, Portuguese, Swedish, and Russian efforts with each other and American efforts with colonial efforts in other parts of the world-in order to separate the unique from the typical.

(11) The well-modulated public and scholarly success of the Quincentenary should inspire us to design future historical anniversaries as opportunities less for celebration than for cerebration. We must also be very careful about who is included in, and who feels excluded from, “We the

People.” Ethnic, gender, and racial sensitivities are likely to grow; parity of treatment and attention-and, perhaps as important, the appearance of parity-must be extended to all citizens, past and present. We can start by rethinking our historical vocabulary: Old and New World, discoverer, discovery, Indian, Amerindian, America, American, Latin American, and the West are factually, morally, or culturally problematic.

(12) Finally, we should all study to become better citizens of the “global village” we now inhabit, the foundations of which Columbus laid in I492. If we do not learn to protect, respect, and sustain its people and to conserve and renew its resources, it will be much poorer when the Columbian sexcentenary occurs. Perhaps some of the lessons we draw from our study of the first Encounter will prevent such a fate.

I make no judgement as to what has happened in the academic arena. I leave that to the scholars in the field. In the public arena, the story is more telling. With the passage of time, Columbus has become even more of a villain to politically-corrected white people. We are quicker to pass judgement now and more vehement and vicious in so doing. The interest now in pre-contact American Indians has more to do with the superiority their way of life to that of white people with all white peoples of all nations being lumped together. Instead of the Encounters leading to a better understanding of all the people and peoples involved, two-dimensional clichés trump all other concerns.

Can we do better? Consider this example from Lewiston, New York, on what one community is doing better and that there is more to be done. From the Historical Association of Lewiston newsletter which is sent to me:

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES DAY

Please support scholarship fund

Indigenous Peoples Day is a day to celebrate and honor Native Americans and to commemorate their shared history and culture. The Village and Town of Lewiston celebrate both Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples Day simultaneously.

At the Historical Association of Lewiston, we decided to honor our Tuscarora neighbors, by awarding a scholarship to a deserving Tuscarora student. It is our hope to make this an annual award given out every year on Indigenous Peoples day in front of the Tuscarora Heroes Monument on Center Street in the Village of Lewiston.

As a non-profit organization, the Historical Association is soliciting public donations to help sponsor the scholarship. We hope you will find it worthy of your generosity and urge you to support this cause. Your donations can be made to the Historical Association of Lewiston, P.O. Box 43, Lewiston, NY 14092. Make a note that you want your donation to go to the Tuscarora Scholarship fund. We can provide you with a receipt for tax purposes if requested. Thank you!

The good news is that the community is recognizing the Tuscarora. The shortcoming is that the Tuscarora are not included in the title of the holiday. With Columbus, there is a proper noun and no confusion as to who is being celebrated. With Indigenous, the people honored could be anywhere in the world: indigenous Canadians, indigenous Australians, indigenous Latin Americans (see Columbus Day versus Indigenous Peoples’ Day: Part II – Columbus and America). If Lewiston has a Tuscarora Heroes Monument then it should have Tuscarora Day as well and it should be on a day most relevant to the Tuscarora.

Here is another example, this time from the Museum of the City of New York (MCNY).

Native American Heritage Day

Sunday, October 13, 11am–12pm

Celebrate the vast history and contemporary voices of Native American New Yorkers who come from Tribal Nations across the country. Enjoy storytelling, songs, and dances performed by the renowned Thunderbird American Indian Dancers, the oldest resident Native American dance company in New York. See Lenape objects in New York at Its Core and contemporary art by Native American New Yorkers in Urban Indian: Native New York Now, and create art to take home.

Notice the dichotomy. The Thunderbird American Indian Dancers call themselves American Indians while the MCNY quickly switches to its preferred politically correct term. But it does call the Lenape by their name and does use the term “Indian” in the exhibit name.

At the recent James Fenimore Cooper & Susan Cooper Conference: “E Pluribus Unum: Cooper, Cosmopolis, and American Identity” (SUNY Oneonta, September 25-25, 2019), there was a Commanche presenter. She always referred to herself as a Commanche or to American Indians in general. It was the white people who used the term “Native Americans.”

In the New York Times on October 13, 2019, just after October 12 and before the Monday holiday, in an article entitled “Sharp Cuts in Immigration Threaten U.S. Economy, Austan Goolsbee wrote about the positive impact immigrants have:

…the evidence increasingly says having immigrants here makes workers born in the United States more successful.

That’s partly because immigrants start companies at twice the rate of native Americans.

How the New York Times let this reporter get away with such politically incorrect language is a mystery. And if you read the sentence aloud, how could you distinguish between “native Americans” and “Native Americans” anyway?

To make matters worse, the Sunday Review section of the New York Times on the very same October 13 day, had a big front page picture and article by Brent Staples entitled “How Italians Became White,” another part of the Columbus Day story that deserves to be remembered (for the Italians see Columbus Day versus Indigenous Peoples’ Day: Part II – Columbus and America).

The Encounter theme proposed by Axtell back in 1992 is the way out of this morass if we want a “win-win” resolution rather than a “zero-sum” war. It applies not only to Columbus Day but to the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution which is now gearing up (we have a meeting tonight on this event).

In New York, where I live I can consider three excellent places where to have encounters, perhaps annual rotating conferences).

National Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian – this location in lower Manhattan is the area where Hudson and the Lenape made contact leading to the creation of New Amsterdam and then New York.

The William Johnson state and private historic sites in the Mohawk Valley – Irish Johnson was the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs whose career involved him with numerous Indian tribes and nations and European nationalities.

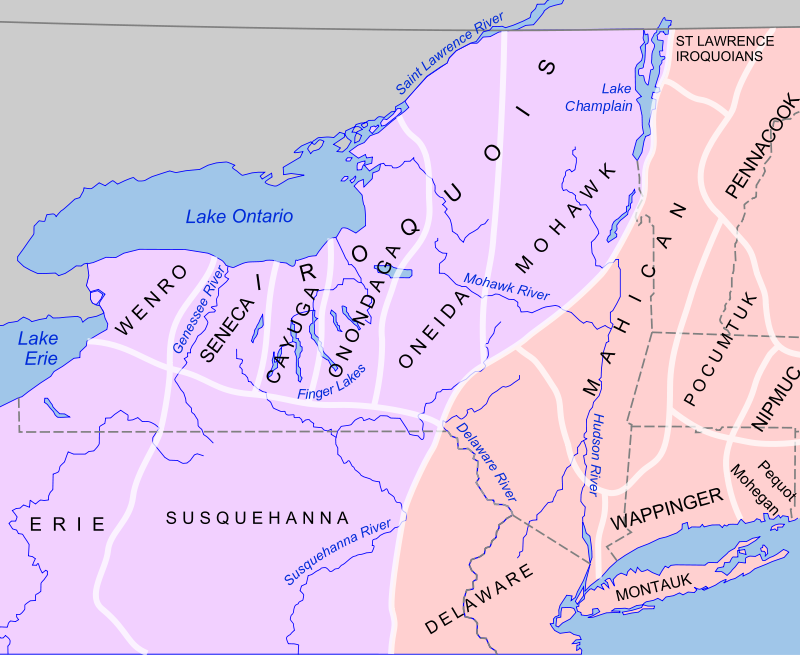

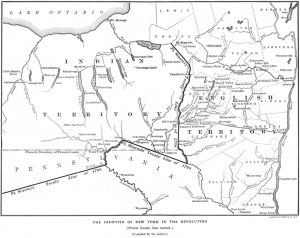

Battle of Oriskany in the Mohawk Valley – This prelude to the Battle of Saratoga revealed that not only was the American Revolution a civil war among European peoples, it was a civil war among Indian peoples where two members of the Iroquois/Haudenosaunee confederation, the Seneca and the Oneida fought on opposite sides against each other.

One could add Cooperstown of Leatherstocking fame, Thanksgiving, Lewis and Clark, Little Big Horn, and a slew of western sites as places of encounters. As things stand now, slice and dice trumps We the People but I prefer to believe that there will come a time when American Indians are recognized as being part of the American experience and Columbus is an individual human being.

Columbus Day versus Indigenous Peoples’ Day: A Lose-Lose War

Columbus Day versus Indigenous Peoples’ Day: Part II – Columbus and America

Columbus Day versus Indigenous Peoples’ Day: Part III- The Meaning of “Indigenous”