In 2000, Mel Gibson released The Patriot. On one level, one could view the movie as another stirring action story in the tradition of Braveheart. If the characters in the movie weren’t exactly historical that was OK; it was set in a real war with real locations and the good guys won. The movie wasn’t intended to be “the true story” of some specific individual or individuals, so relax and enjoy the entertainment.

There were certain caveats which rendered the escapism troublesome. Certainly the British didn’t fare too well as human beings. They were more in the tradition of Romans or Nazis in the Gibson universe. More troubling perhaps was Gibson’s presentism. Presentism refers to the retrojection of cultural values of the present into the past. It is the judgmental equivalent of having Washington use satellite imagery to locate the British troops or having Elliot Ness read Al Capone his rights. Typically, presentism is used to cast negative judgment against people in the past, to knock them off their pedestal, to take them down a notch, to make the judge, jury, and executioner of reputations in the present superior to the targeted person in history. It is not such much about setting the record straight as it is in being morally superior and self-righteous. There is no “walk a mile in someone’s shoes” or sensitivity in presentism.

Gibson used presentism in a different sense. Instead of retrojecting politically correct values to condemn someone in the past, he retrojected the values to create a community living in accordance with them. Gibson’s secret hideaway for fugitives from the British was a kumbaya community of people living in harmony with each other regardless of race or gender. Except for the fact that there was a war going on out there somewhere in the real world, Gibson’s “Gilligan’s Island” exemplified life as it should be lived in an idyllic setting. As one might expect, Gibson was taken to task for this artificial reality he created in the American and southern past.

Artists, unlike honest biographers, have choices to make about what to include or exclude in an artistic creation. After all, everything can’t be included. In the commencement address last spring at the University of Pennsylvania, Lin-Manuel Miranda discussed the power of stories to shape our lives and expressed the realization that story-telling is an act of pruning the truth, not representing it in its entirety. Miranda said:

Every story you choose to tell by necessity omits others from the larger narrative. One could write five totally different musicals from Hamilton’s eventful, singular American life … For every detail I chose to dramatize, there are 10 I left out. I include King George at the expense of Ben Franklin. I dramatize Angelica Schuyler’s intelligence and heart at the expense of Benedict Arnold’s betrayal. James Madison and Hamilton were friends, and political allies-but their personal and political fallout falls right on our act break, during intermission. (The Pennsylvania Gazette July/August 2016, 15)

Miranda’s Hamilton in one striking inclusion and one striking omission demonstrates that Mel Gibson is alive and well in the portrayal of the American Revolution. In his commencement address, Miranda referred to one of the defining stories this presidential election year.

In a year when politicians traffic in anti-immigrant rhetoric, there is also a Broadway musical reminding us that a broke, orphan immigrant from the West Indies built our financial system. A story that reminds us that since the beginning of the great unfinished symphony that is our American experiment, time and time again immigrants get the job done. (The Pennsylvania Gazette July/August 2016, 15)

Miranda is to be praised for reminding us that America from the start has been an unfinished experiment and that the journey continues. That expression is part of why Hamilton is the great sign that the journey will continue to be a successful one, that the work that still needs to be done, will be done. But he can be faulted for going overboard on Hamilton the pro-immigrant person based on politically correct values in the present. In the musical, the line “immigrants get the job done” generates the loudest applause. There is no doubting its theatrical effectiveness in New York City in 2015-2016 and beyond. There also is no doubting it is an example of Mel Gibson kumbaya.

In the musical, Hamilton and Lafayette high-five each other as they exclaim this thought. Technically, of course, Lafayette, was not an immigrant but a visitor. The musical does not specifically identify him as an immigrant but it is easy to infer that he is if one didn’t already know better. Immigration during the war wasn’t a big issue. There was more concern about Loyalist Brits returning and participating in the American political entity than about non-British immigration. It would be decades before immigration would become an issue with the arrival of America’s first “Moslems,” the Catholics who pledged loyalty to a foreign master and who were going to infiltrate and take over the country. Do you know how matter Catholics there are on the Supreme Court today? And as Republicans!? One may raise legitimate issues about how welcoming Federalist Protestant Hamilton would have been of the arrival of multitudes of riff raff. But not in the musical Miranda chose to write.

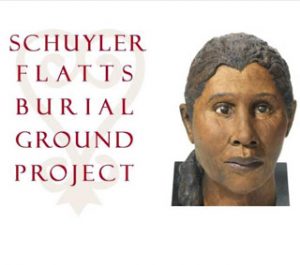

Similarly there is a race problem. Hamilton was not a slave owner and he did join John Jay’s manumission society. On the other hand, he did marry into a slave-owning family. Just recently, there was ceremony at Schuyler Flatts in Colonie, just north of Albany, of the remains of 14 of the Schuyler slaves. They were first discovered during a construction project in 2005 and then analyzed by the New York State Museum in 2010. I tried to go there as part of Teacherhostel/Historyhostel, but was informed by the New York State archaeologist that there was nothing to see at Schuyler Flatts. It just was flat piece of land. Now there are artistically-created burial coffins for these people. So while Hamilton casts some of the Schuyler daughters as black it does not address the slaves those daughters owned through their father. Not an easy subject for Miranda’ musical but an essential one for a biography by a historian.

Gibson’s presentism continues on in the AMC series Turn, another American Revolution story with 21st century values. I refer here not to John Graves Simcoe, the future founder of York, now named Toronto. In the TV series he is cast in the Darth Vader role as a “ruthless attack dog” according to the website. I am referring to Anna Strong, the older married woman with children who is transformed into a sexy tavern wench lusted for by men on both sides of the conflict. But at the Turn panel discussion at the New-York Historical Society last spring, the audience was informed that the character’s position would take a turn for the better in season three. She would be transformed this time into an active participant in the spy ring who travelled about and contributed to the decisions made. Her travels take her to John André’s black servant, Abigail, a former slave in the Strong household. The scenes involving Anna, Abigail, and her son are dangerously reminiscent of Gibson’s kumbaya community in The Patriot. One might wonder if the enhanced role for the lead female figure was due to some new discovery or scholarship but that would be foolish. The decision, of course, was a marketing one to provide a character to appeal to the desired demographic. If changing this bewitching female into a witch would help ratings then that might be considered too except The Legend of Sleepy Hollow already has that niche covered for the American Revolution.

Overall, it is good that there is such interest in the birth of the country. After all, we never were a country of one ethnicity or religion. That demographic diversity is part of the reason why we have continued to exist even as the number of ethnicities (Palatines-Irish-Italian-Indian) and religions (Methodist, Catholic, Jewish, Moslem) continues to grow. We are better as a country if we continually return to the story of our birth as country to make the story relevant to We the People today. Take a look at the story of the Exodus and see how many times Moses climbs up and down the mountain and all the activities at the mountain and you see examples of Exodus Midrash, the Jewish tradition of retelling the story of the foundation of the people, a tradition which continues today both in the different Passover ceremonies which are held and the different Exodus movies which are made. Mixed multitudes and diverse demographics become one in the ideas that constitute or covenant them as a single people. To stop telling the story of that birth is to die as a people, to cease to exist as a culture. But there are limits. The presentisms of Mel Gibson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, and AMC are not the first time the story of the American Revolution was retold and won’t be the last. In fact, part of the story of America, is the recognition that we are telling and retelling the story of our birth again and again.

An excellent post but I want to read the end of it…it looks like it got cut off?

Good catch. For some reason the final words are missing “and retelling the story of our birth again and again.”

I have added them

I abhor attempts to judge the people and events of the past through the “political correctness” lens of the present as much as I do projecting current sensibilities on them. That said, I question the “Gibson’s ‘Gilligan’s Island’ exemplified life as it should be lived in an idyllic setting” comment. A mid-twentieth century allegory of Dante’s “Inferno,” the apparent “idyllic setting” was actually the Hell to which the “seven stranded castaways,” each representing one of the “Seven Deadly Sins,” had been condemned to punishment by their own devices, and could never escape.

Thanks Glenn. I confess I may have been a bit flippant choosing the Gilligan Island and have never contemplated its deeper significance.

It is not accurate to refer to “Gibson’s presentism” or the “Gibson universe.” The Patriot was directed by Roland Emmerich and written by Robert Rodat. Mel Gibson was not one of the producers; he was simply an actor. It’s more accurate to call it Emmerich’s or Rodat’s film.