Museums have a history, too. Museums today the repositories of historical artifacts available to scholars and the general public alike. However that was not always so. There is a history of how museums came to be what they are today. This topic was the subject of two presentations at conferences in June: “Entertainments at Taverns and Long Rooms in New England, 1700-1900” at Historic Deerfield and in the keynote address at the Massachusetts History Alliance conference at Holy Cross. In addition, there is an article in the current issue of Near Eastern Archaeology about the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the 19th century that directly relates to this topic even though the specific artifacts in question are from overseas.

MUSEUMS ON THE ERIE CANAL CORRIDOR, 1820-1836

Paul E. Johnson, University of South Carolina

Abstract: In early 1820 there were no museums in New York west of Albany. By 1836 there were permanent museums in Utica (1820), Geneva (1830), Syracuse (c. 1830), Oswego (1836), Auburn (1832), Rochester (1825), Buffalo (1829), and Niagara Falls, Canada (1833). I…will focus on the museum of William Stowell and Justin Bishop at Rochester. It is well documented and its origins in New Haven, its itineracy before moving west, and its long tenure in Rochester permits discussion of the full sweep of early nineteenth-century museum history.

The upstate museums varied considerably, but they had much in common. First, none of them received support from governments or learned societies. They relied on ticket sales to stay in business. All maintained collections of minerals, stuffed birds and animals, paintings, and local curiosities. They used them to provide a respectable setting for variety acts ranging from trick dogs to giants and dwarfs to Indian war dances to demonstrations of laughing gas.

Professional entertainers drew visitors, but the principal everyday attraction was wax figures. While Charles Willson Peale [of mastodon fame in Orange County, New York] used wax figures solely as mannequins for his costume collection, the Boston and New York museums followed the lead of Madame Tussaud. She filled her London museum with kings and queens, poets, generals, and other notables. They were posed in quiet elegant surroundings. Museum patrons spoke softly and minded their manners.

Early seaport museums did not try to thrill visitors with their wax galleries. They tended to portray violence: Louis XVI preparing for the guillotine or Aaron Burr leaving the scene after mortally wounding Alexander Hamilton. Waxworks in early museums were part of the furniture of the room and not stand-alone attractions.

The western museums were less decorous. First they displayed most of their figures in tableau and not as individuals. The Rochester Museum put these groups behind glass. This action transformed the visitors into an audience that had not wished to join the scenes of Richard M. Johnson killing Tecumseh, an American officer who is killing an Indian who is scalping a boy, Chief Black Streak killing a settler, and Andrew Jackson killing Black Streak. Few sources describe the wax tableau in detail. Those that do reveal that the museums played up the violence. In Rochester, Othello was stabbing (not smothering Desdemona).

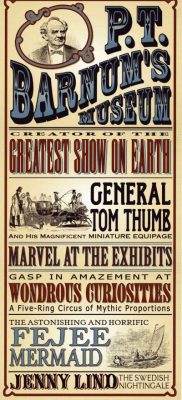

Finally, the upstate museums anticipated P. T. Barnum and hoaxed their patrons. When the Syracuse Museum burned down in 1834, customers discovered that the great sea turtle was made of leather and painted, and that the anaconda was a long sleeve stuffed with cotton. Rochester museum-goers always doubted the three-foot oyster shell. Patrons leaving the museum passed a picture of two donkeys facing each other. A caption read “We Three Will Meet Again.” A customer reported that he felt both cheated and entertained.

In his presentation, Johnson described museums as peaceful places but not scientific. But he also said the sensationalism of the wax figures were a chamber of horrors meant to cause children to scream: they show the moment the husband’s ax strikes the wife’s head! Museums were not educational as much as they were entertainment. The Canal Museum plied the waters of the Erie Canal showing its wares much as Showboat would do on the Mississippi but without the live performers.

DISCOMFORT AND RENEWAL: THE ABBE MUSEUM (MAINE)

Cinnamon Catlin-Legutko, President/CEO, Abbe Museum

Catlin-Legutko delivered the keynote address at the Massachusetts History Alliance conference. Her theme was the dismantling of the institutional racism of her museum. According to the museum website:

One mission, two locations – Inspiring new learning about the Wabanaki Nations with every visit

In recent years, the Abbe has grown from a small trailside museum, privately operated within Acadia National Park, to an exciting contemporary museum in the heart of downtown Bar Harbor. In 2013, the Museum became the first and only Smithsonian Affiliate in the state of Maine.

At the Abbe’s downtown museum, visitors find dynamic and stimulating exhibitions and activities interspersed with spaces for quiet reflection. The history and cultures of the Native people in Maine, the Wabanaki, are showcased through changing exhibitions, special events, teacher workshops, archaeology field schools, and workshops for children and adults.

From spring through fall, the Abbe’s historic trailside museum at Sieur de Monts Spring continues to offer visitors a step back in time to early 20th century presentations of Native American archaeology in Maine.

Catlin-Legutko referred to her museum as having been a colonial museum with a troublesome relationship with the Wabanaki. The museum exhibits were sterile display cases. The museum tended to homogenize the multiple Indian nations and tribes of Maine into one individual group. One might think from the presentation at the museum that it was referring to an extinct people.

For the Indian audience, the visit was painful. They had no rapport with the museum.

The museum board was elitist and white.

Under Catlin-Legutko’s stewardship the Abbe Museum underwent a “decolonizing” program. Now the term pre-history was out [technically the term “prehistoric” refers to a pre-writing people although the popular usage is different]. Now a place of privilege is given to the Indian history. They are not simply a people who were removed. Archaeological worked was stopped until new protocols could be developed. The conversations within the board and between the board and Indians were “difficult.”

In the Q&A, someone asked about DNA research. Apparently now everybody wants to be “native.” There is a romanticization in being connected to a vanishing race. This question and answer directly relates the topic of Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a topic to which I shall return.

My own question was about education. What is taught about the Wabanaki? Catlin-Legutko acknowledged the issue of the state-mandated curriculum. The museum has increased teacher training, school contacts, and posting curriculum on its website.

Other presentations from the Massachusetts History Alliance conference will be covered in future blogs.

THE METROPOLITIAN MUSEUM DISPLAYS IN THE 1870s

The article in question is by Ann-Marie Knoblauch: “The Mainstream Media and the ‘Shocking Bad Art’ from Cyprus: 1870s New York Reacts to the Cesnola Collections” (Near Eastern Archaeology 82 2019 67-74). While there are vast differences in the story at the Met and the Abbe, there are similarities as well. One obvious similarity is in the questionable means for obtaining the objects in the first place. One obvious difference is the international competition for objects in which the Met participated against museums in England and France whereas this was less of an issue in Maine.

One area in common was the putdown of both the Wabenaki and the Cypriots. The article refers to the ideal standard of beauty with which the museums operated: it was based on the Greek art of classical and Hellenistic periods [before and after Alexander the Great]. No surprise there. But this shows that “white” civilizations could be perceived as substandard as well.

The display of the objects at the Met was overwhelming and sterile although that word was not used in the article. As reported in the New York Herald (August 4, 1878), the public response was one of apathy. Luigi Palma di Cesnola responded by besmirching the New York audience. Again as reported by the New York Herald:

It is that unfortunate word “museum” that the General [Cesnola] attributes in a great measure the lack of popularity of the institution. To the scholar “museum” means “temple of the museums,” but to the untraveled New Yorker it means Barnum, mermaids, wooly horses and Bowery shows of fat women exhibited by shouting ruffians to the sound of a hurdy-gurdy.

So when did museums stop meaning Barnum and become the educational and scientific institutions it means today…while still being entertaining?