What do Egyptologists think of the Exodus? In The Exodus, An Egyptian Story, I examined leading (English) histories of Egypt from 1905 to 2010 to determine what these prominent Egyptologists thought about the Exodus. Later in the book, I repeated the process to see what these same people or co-authors if a multi-authored book, thought about the Hyksos. Only then did I offer my own historical reconstruction.

Below are 8 examples. I have excluded some well-known Egyptian books which had nothing to say about the Exodus.

1905 A History of Egypt: From the XIXth to the XXXth Dynasties by W. M. Flinders Petrie. He appears to take the position that the mention of Israel in the recently-discovered Merneptah Stela complicates rather than elucidates the question of the Exodus.

The name of the people of Israel here is very surprising in every way: it is the only instance of the name Israel on any monument, and it is four centuries before any mention of the race in cuneiform: it is clearly outside of our literary information, which has led to the belief that there were no Israelites in Palestine between the going into Egypt and the entry at Jericho; whereas here are Israelites mentioned with Ynuamu in North Palestine, at a time which must be while the historic Israel was outside of Palestine. The only likely conclusion is that there were others of the tribe left behind, or immediately returning, at the time of the famine; and that these kept up the family traditions about sites which were known in later times (114).

According to this view, not all the Israelites sojourned to Egypt or else some returned fairly quickly. Merneptah then attacked these Israelites already in the land of Canaan and not those who left in the Exodus. Petrie recognized that this view created a problem. He attempted to resolve his dilemma through reconciling biblical chronologies and Egyptian texts on Semitic people entering Egypt in the time of Merneptah.

Some objection may be raised to accepting the periods stated in the early Israelite history; but if their residence in Egypt is granted, we must suppose that they had an educated class which could keep the necessary accounts and records which were an incessant feature of Egyptian life. The known character of the Egyptian and Syrian civilisation of the time must cause a great difficulty to those who would deny all use of writing to the Israelites. The details of the course followed by the Israelites at the Exodus have been much disputed, owing to the insufficiency of data; but the result of Naville’s discussion of it is reasonable and generally accepted [N(aville). P(ithom). 27] (115).

He appears to be citing The Store City of Pithom and the Route of the Exodus but I am not sure about the page reference (Naville 1885).

1912 A History of Egypt, from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest by James Henry Breasted: He had written about the discovery of the Merneptah Stela with its mention of Israel as soon as the discovery had been made. Certainly he was current with the archaeological work that might touch on the Exodus. In his own history of Egypt, Breasted wrote:

There is probably little question of the correctness of the Hebrew tradition in attributing the oppression of some tribe of their ancestors to the builder of Pithom (Fig. 162) and Ramses; that a tribe of their forefathers should have fled the country to escape such labour is quite in accord with what we know of the time (1912, 446-447).

Breasted even posited a route for the Israelites to take in their departure.

Although there was never a continuous fortification of any length across the Isthmus of Suez, there was a line of strongholds, of which Tharu was one and probably Ramses another, stretching well across the zone along which Egypt might be entered from Asia. This zone did not extend to the southern half of the isthmus, but was confined to the territory between Lake Timsah and the Mediterranean, whence the line of fortresses extended southward, passed the lake and bent westward into the Wadi Tumilat. Hence Hebrew tradition depicts the escape of the Israelites across the southern half of the isthmus south of the line of defences, which might have stopped them (1912, 447)

Breasted finally referred to a dilemma caused by the Merneptah Stele. It seemed to verify the Exodus event while simultaneously casting doubt on the biblical account.

After a reign of at least ten years Merneptah passed away (1215 B.C.) and was buried at Thebes in the valley with his ancestors. His body has recently been found there, quite discomfiting the adherents of the theory that, as the undoubted Pharaoh of the Hebrew exodus, he must have been drowned in the Red Sea! (1912, 472).

1924 The Cambridge Ancient History with contributions by James Henry Breasted on “The Age of Ramses” and S. A. Cook on “The Rise of Israel.” Breasted’s chapter repeats what he had written in his own history of Egypt.

Foreign intercourse, especially with Palestine and Syria, was now more intimate than ever….Although there was never a continuous fortification of any length across the Isthmus of Suez, there was a line of strongholds, of which Tharu was one and Per-Ramses another, stretching well across the zone along which Egypt might be entered from Asia. This zone did not extend to the southern side of the isthmus, but was confined to the territory between Lake Timsah and the Mediterranean, whence the line of fortresses extended southward, passed the lake and bent westward into the Wadi Tumilat. Hence it is that Hebrew tradition depicts the escape of the Israelites across the southern half of the isthmus south of the line of defences, which might have stopped them (1924, 153)….

The country swarmed with Semitic and other Asiatic slaves. It is quite plausible that Ramses II, probably the builder of Pithom and Raamses, store-cities of the eastern Delta, should have been the Pharaoh who figured in the tradition of the Israelites, and that a group of their ancestors, after a friendly reception, were subjected to slave labour in the building of the two places mentioned (1924, 154).

Merneptah passed away (1215 B.C.) after a reign of at least ten years and was buried at Thebes in the valley with his ancestors. His body has been found there —a discovery somewhat disconcerting to those who held that, as the Pharaoh of the Israelite exodus, he must have been drowned in the Red Sea (see p. 356,n. 2) (1912, 170).

The implication is that an Exodus did occur.

Cook devotes approximately 25 pages to the topics of the biblical text and the Exodus. His interests are more textual than archaeological. He summarizes the biblical account of the Exodus and Conquest. He refers to the literary process of the creation of the textual record which concluded centuries after the date of Ramses or Merneptah. There is no evidence for either event. He spends a great deal of time examining the biblical text in the land of Canaan (and the wilderness) and less so in Egypt itself. The clearest expression of his views appears in two footnotes:

1. While the strongest arguments against the ‘critical’ position have indicated the weakness of elaborate ‘reconstructions’ based upon data which prove to be much more complicated than was thought, no alternative position and no other fruitful lines of enquiry have attracted serious attention.

2. Four groups of theories have prevailed as to the Exodus. Broadly speaking, they associate themselves with (i) the Hyksos (i.e. before the XVIIIth Dynasty), (2) the age of Thutmose III and Amenhotep III and IV (the ‘Amarna Age,’XVIIIth Dynasty); (3) the age of Ramses II and Merneptah (XIXth Dynasty); and (4) a later period (XXth Dynasty). Each of the groups has points in its favour, but deals so drastically with the biblical evidence that should any one of them be justified (through fresh external evidence), the very secondary character of the biblical narratives will only be more unmistakable. Most can be said in favour of (2) and (3); cf. p. 153 sq. [referring to Breasted’s contribution above] (1924, 356).

All in all, Cook does not give much credence to the Exodus account.

1951 The Burden of Egypt by John A. Wilson: The revised title, The Culture of Ancient Egypt, for this edition probably reflects an editorial decision to reduce the judgmental harshness of the original title. However, his antithetical views towards Egypt shine through especially when he was contrasting Egypt with Israel. Wilson included references to Hebrews at scattered moments in his telling of the Egyptian story and delivered a powerful message through them. He concluded his chapter on the First Intermediate Period entitled “The First Illness” with the observation that the “disciplined unity of the state became more important than the rights and opportunities of individuals, the concept of equality and social justice was finally swallowed up. This was the story of a people who once caught a clear but distant view of the Promised Land who ended up wandering in the wilderness” (1951, 124). Here Wilson was disparaging Egypt for having discovered the value of the individual man and then abandoning it. The implication is that Israel succeeded where Egypt failed.

Wilson rejected the notion that Atonism, the religion of Akhnaton was ancestral to Hebrew monotheism (1951, 225-229). He concluded this section with the comment that “The fuller realization of the meaning of God’s cherishing care was to be made by other and later peoples”(1951, 229).

Wilson declared that the Merneptah Stela mentioning Israel means the “Exodus of the Children of Israel from Egypt” had to have occurred earlier (1951, 255). He stated his own thesis that the Hebrews took little from Egypt and expressed his obligation to present his own view of the Exodus. For Wilson, the biblical account “is a simple and honest attempt to tell the tale of Jahweh’s preservation of His people and is given simplicity and directness for the purposes of national cohesion by making the climax the deliverance of the people from the mighty Egyptian nation” (1951, 255).

Wilson provided some details on how this happened. His Israel truly was a mixed multitude. It consisted of people who had had an exodus from Egypt under the Hyksos, were subjects of the Egyptian Empire in Palestine, were captives taken to Egypt, were Habiru, and were a small group who succeeded in making the Exodus from Egypt. That Egyptianized group outwitted some Pharaoh and escaped into the Sinai wilderness. This group is the tribe of Levi and they were missionaries of a new cult. That cult “struck a responsive chord in every heart which had suffered under Egyptian domination” (1951, 256). The Levites brought unity to the diverse peoples of Canaan.

Wilson expressed scant regard for the people these Israelites left. As slave troops on building projects, they were in no position to learn the ways of Egypt nor should they have wanted to. “Their simple desert souls would see and shrink from some of the abominations of the effete civilization and long to escape dreary enslavement rather than admire the cultural triumphs of the land of bondage … By the time the Hebrews were intellectually mature enough to seek for models of expression from neighbors, Egypt was a senile and repetitive culture, which had nothing dynamic to give” (1951, 256; see also 251). Wilson concluded his book with additional denunciations of the Egyptian way of life compared to the Hebrews and the Greeks (1951, 314-318).

1961 Egypt of the Pharaohs: An Introduction by Sir Alan Gardiner – Gardiner alluded to the Exodus without taking a stand. He mentioned the Merneptah Stela and various wilderness-related inscriptions proponents of an historical Exodus cite but never definitively offered his own opinion despite his earlier supposition about the Hyksos. (See previous post The Egyptian Exploration Fund and the Exodus for Hoffmeier’s comment on the impact of Gardiner on separating Egyptology from Exodus studies.)

1975 “Egypt: From the Inception of the Nineteenth Dynasty to the Death of Ramesses III,” in The Cambridge Ancient History by Raymond Faulkner – Faulkner has little to say except to dismiss the Exodus as an event in history

The second point that arises is the mention of Israel, the only instance known from any Egyptian text. Until the discovery of this stela in 1896 the general belief was that Merneptah was the pharaoh of the Exodus, yet here in the middle of his reign we find Israel already settled in Palestine. Discussion of this problem has been endless, but the fact remains that there is no positive evidence relating to the date of the Exodus (1975, 234).

1988 A History of Ancient Egypt by Nicolas Grimal (1992 English translation) – “It is considered possible that the Jewish Exodus may have taken place during the reign of Ramesses II” (1988, 258). Grimal then mentioned the “Apiru” implying they might be a source for the people of the Exodus without stating it. He noted that there is no surviving record of the Exodus in Egyptian sources which he did not think was surprising: “the Egyptians had no reason to attach any importance to the Hebrews” (1992, 258). Grimal deemed it “possible to reconstruct the course of events leading up to the Exodus…” (1992, 258). He did so through the Egyptian education Moses would have received as a member of the court in the time of Horemheb (1323-1295 BCE). He posited that Seti I then would have sent this trained person back to his people to assist in the building of the fortifications in the eastern Delta and the future city of Piramesse. He dated Moses’s murder of the Egyptian guard, flight to Midian, marriage, acceptance of the Burning Bush revelation, and return to Egypt to the first years of the reign of Ramses II. Grimal treated Pharaoh’s objection to allowing the Hebrews to depart into the wilderness as understandable given that this territory was a constant threat during years two to eight of his reign (1988, 258-259).

2010 The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt by Toby Wilkinson – He accepted that the building activities at Per-Ramesses, the capital under Seti and Ramses II, provided a background for the biblical building stories. He characterized the likely Semitic-speaking laborers on the building projects as migrant workers rather than slaves. The sources are silent on any Exodus of the Hebrews. He opined that the biblical story may be a conflation of multiple unrelated historical events. However, he acknowledged that “Ramses was not one to let the truth stand in the way of his news agenda” (2010, 313).

None of these Egyptologists seem to have considered the possibility that Ramses claimed success in the Exodus just as he had at Kadesh … or to recognize that portions of his claim of victory at Kadesh were composed after his failure in the Exodus as well. Come to think of it, neither do biblical scholars.

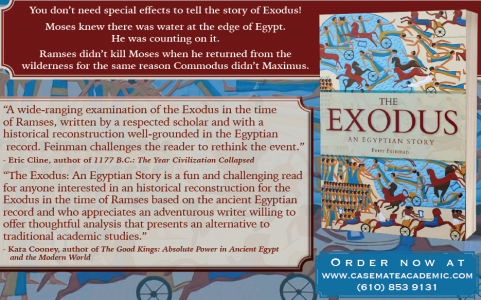

This half-page ad will appear in the forthcoming issue of KMT