Recent years have seen the growth of two related and possibly contradictory developments in Indian-American relationships: land acknowledgments and mascot removal. Both have been in the academic news lately.

In the November issue of Perspectives on History of the American Historical Association, there is an article “Land Acknowledgements: Helpful, Harmful, Hopeful,” by Elizabeth Ellis, the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, and Rose Stremlau (tribe not stated).

Also in November, the New York State Education Department issued a directive calling for the elimination of Indian-related mascots this school year or school districts will be penalized.

There is more to the story than this.

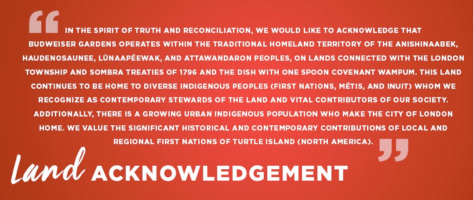

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

According to the authors,

…many Indigenous communities and scholars have become more critical of the use and performance of these statements that lack ongoing relationships with and commitments to Native nations in their region or scholars, students, and staff on their campuses.

They take the process to task:

…many academic institutions here have created statements without understanding historical context, Indigenous cultural protocols, or the current political and economic experiences of the people to whom they refer.

They object to the abuse of the practice:

…most land acknowledgements no longer resemble the ritual, relational tellings of their origin, and many are deeply problematic.

They are tired of hearing generic apologies to all Indian peoples that ring with insincerity. They have endured painful incantations of mispronounced names. They have watched others (and presumably themselves) be trotted up to the microphones to recite them and then be applauded while they are whisked off stage (or off screen).

At times, they can be fairly harsh:

…when land acknowledgements are delivered as rote statements at the beginning of an event, and when there is no further discussion of these Indigenous pasts and presents, the acknowledgements tend to feel inauthentic and performative.

The authors compare this to introducing a speaker by including their office hours.

This description tends to match the land acknowledgements I hear at the beginning of lectures even for talks that have nothing directly to do with the pre-Contact inhabitants of the land.

By coincidence, in an online interview in a totally unrelated subject, Jeffrey Goldberg, editor Atlantic magazine, asked a similar question about markers in Germany designed to remember the deceased from the Holocaust. As he somewhat flippantly put it, are these markers like land acknowledgements – once you recite them, then it is on with the show.

The authors believe in the potential and opportunity expressed within land acknowledgements but don’t see it happening. Both teach in parts of the east where the visible presence of Indians is minimal. One is in New Jersey. The other in the Carolinas where most Americans [non-Natives to them] “believe the Trail of Tears resulted in the removal of all Native people from the region – this despite the presence of federally and state-recognized nations and urban Indian communities in those states.”

Rather than the perfunctory reciting of land acknowledgments at the commencement of a lecture or event, they envision the beginning of a conversation about both the past and the present. However, such conversations really require a separate event or series of discussions beyond the individual lecture. They are seeking “serious engagement.” They want land acknowledgements “to tell stories that connect people so we can work collaboratively, address historic and ongoing harm, and forge relationships among Native nations and institutions.”

One suggestion for improving the article is to have included examples where such serious engagement has occurred. I have written blogs about the Florida State University and its relationship to the Seminole Tribe of Florida (Ireland Sues Fighting Irish over Hostile and Abusive Name after Notre Dame’s Bowl Victory December 31, 2019 and Should Chief Daniel Nimham Be Honored or Erased? December 14, 2021). The tribe website states “We are a Federally Recognized Indian Tribe. The only Tribe in America who never signed a peace treaty.”

Coincidentally, I recently received a notice for a talk (December 18, 2022) by Stockbridge-Munsee Community Tribal Historic Preservation Manager Bonney Hartley who guides the historic partnership between Williams College and the Stockbridge-Munsee Community.

These two examples highlight the shortcomings of the rote performative land acknowledgment. They could be used to illustrate what could be done.

The critical questions buried in the middle of the article are: “For whom are we saying these words, for what reasons, and with what intended outcomes?’ The answer, of course, is for white people. The purpose of land acknowledgements is not to engage in serious conversations or have collaborative engagements especially, work collaboratively, address historic and forge relationships. Usually land acknowledgements are irrelevant to the program which follows and done in isolation. To understand land acknowledgements, these piously spoken perfunctory recitations devoid of any meaning one should ask what do they mean to white people. They are a little like watch white actors recite Hail Marys, Forgive Me Father for I have sinned in a movie or TV show and about as believable.

MASCOTS

The New York State Education Department issued a directive November 17, 2022. The Deputy Commissioner wrote:

The New York State Education Department (NYSED) wishes to ensure school districts’ knowledge of a recent legal decision and their concomitant need to ensure that mascots, team names, and logos are non-discriminatory.

In 2001, former Commissioner of Education Richard P. Mills issued a memorandum “conclud[ing] that the use of Native American symbols or depictions as mascots can become a barrier to building a safe and nurturing school community and improving academic achievement for all students.” He asked boards of education “to end the use of Native American mascots as soon as practical” and many school districts heeded this directive while others have not….

Those school districts that continue to utilize Indigenous/Native American team names, logos, and/or imagery must immediately come into compliance. Should they require guidance, districts may reach out to those districts that successfully retired their mascots or their local Board of Cooperative Education Services. The Department is developing regulations that will clarify school districts’ obligations in this respect.

Failure to comply by the end of the 2022-2023 school year will lead to the removal of school officials and the withholding of school aid.

These actions are taken under the Dignity for All Students Act. That act prohibits “the creation of a hostile environment… that reasonably causes or would be expected to cause… harm to a student.” The language is highly reminiscent of the widespread effort to prohibit CRT and 1619. It is a reminder that both sides can use the same weaponized terminology. It shows why school board elections have become so contentious.

The establishment of the standard about “hostile environment” from the perspective of the student opens up a can of worms to say the least. Exactly how many Indian students are there in these schools with Indian mascots? While the number is not zero, it is likely very few. By contrast when hostile environment to the student is used with CRT and 1619, it is meant for white students who are quite numerous in the class or school. What the New York State Education Department has done without meaning to is to legitimate the efforts by states to create non-hostile environments in the classroom as defined by the state. Here again, one may observe that the elimination of Indian mascots is to suit the needs of white people and does engage in serious collaboration with any specific Indian nation or tribe.

That being said, the removal of mascots with the term “Indians” makes some sense. “Indian” is not a slur word or term of insult. As noted above, one of the authors belongs to Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma. The photograph used in their article is courtesy of Northwest Indian College. Indians can and do use the term “Indians” since it often is part of their name. For white people not to use the term “Indian” is pretentious. However, to the best of my knowledge there are no high school, college, or professional teams named “Europeans,” “Africans,” or “Asians.” So naming a team “Indians” does perpetuate the idea that if you have seen one Indian you have seen them all.

Terms like ‘warriors,” “chiefs,” “braves,” and “raiders” have been discussed in previous blogs. There is nothing unique to the American Indian about those terms. I have suggested “Klingon” be used to avoid any possible connection to American Indians. Images of knights and gladiators also can be used.

The elimination of Indian mascots will not lead to the serious engagements with a local Indian nation or tribe sought by the authors. Instead it will lead to the erasure of Indians. Eliminating the caricatures and stereotypes is a valid undertaking. But once a school cleanses itself of the Indian mascot, is it replaced with the kind of serious conversation between the two people that Ellis and Stremlau wrote about? I suspect not. The more likely results are the elimination of Indians from the curriculum and the application of the no divisiveness hostile argument into areas not originally intended.

More interesting historical questions about mascots might be when schools started having them, and what percentage of students, parents, staff, and community members became emotionally attached them and why. They’re just to sell merchandise to suckers, aren’t they?

To claim that eliminating “Indian mascots” will lead to “erasure of Indians” sounds very much like a slippery slope fallacy. I fail to see why there’d be any correlation. That said, for serious conversations to happen I’d agree far more would be needed than concentration on issues of land acknowledgements or mascots.

The “erasure” refers to out of sight, out of mind. It would be interesting to know where in the curriculum there is space for teaching about the local Indian nation of a given school district particularly how little there is for teaching local history in the first place.