What is the value of a view? I was reminded of this question in a recent article in The New York Times entitled “Regulate the Skyline? What’s Your View? (Michael Kimmelman, October 26, 2023). Note the play on words in asking for view/opinion and asking for your view/what can you see. The subtitle is “It’s not a new question, but it seems more important than it ever has before.”

The article was mainly about Manhattan. Views of the Empire State Building figured prominently. Not only is the famed building iconic, it also is physically isolated from any nearby rivals. Part of this is due to the bedrock which provides for a sturdy foundation in lower Manhattan and mid-Manhattan but less so in between. One result is that the Empire State Building provides a double view:

1. it provides a 360-degree view from the Observation Deck unencumbered by any intrusions

2. it provides a ground –level orientation point for people not sure where they are getting out of the subway.

Now that view is jeopardized by what the author characterizes as “yet another anorexic supertall for squillionaires.” It will be an 860-foot tall building with 26 apartments

The article recalls one event that actually happened to me. I was headed east bound on 42nd street towards Grand Central to catch a train home. Suddenly I saw what looked like Grand Central but which I had never seen before. I really did not know where I was. It turns out I was looking at the west façade of Grand Central which for years had been blocked from view from a random collection of buildings. Now those buildings had been torn down in preparation for the construction of a 1401-foot tall commercial building that now blocks that view. But for a brief moment there was an opportunity to see Grand Central in its glory when it had been built before it was overwhelmed by its neighbors.

This article triggered something in my mind. It reminded me of view stories in the Hudson Valley. One of the oldest if not the oldest view stories literally is that from James Fenimore Cooper in The Pioneers.

“There’s a place in them hills that I used to climb to, when I wanted to see the carryings on of the world, that would well pay any man for a barked shin or a torn moccasin. You know the Catskills, lad, for you must have seen them on your left, as you followed the river up from York, looking as blue as a piece of clear sky, and holding up the clouds on their tops, as the smoke curls over the head of an Indian chief at the council fire. Well, there’s the High-peak and Round-top, which lay back, like a father and mother among their children, seeing they are high above all the other hills. But the place I mean is next to the river, where one of the ridges juts out a little from the rest, and where the rocks fall for the best part of a thousand feet, so much up and down, that a man standing on their edges is fool enough to think he can jump from top to bottom.”

“What see you when you get there?” asked Edwards.

“Creation!” said Natty, dropping the end of his rod into the water, and sweeping one hand around him in a circle — “all creation, lad…”

So at the same time as the birth of Hudson River School by Thomas Cole, Cooper was describing a view of what was being painted. To see the creation as sun rise was grand sight indeed.

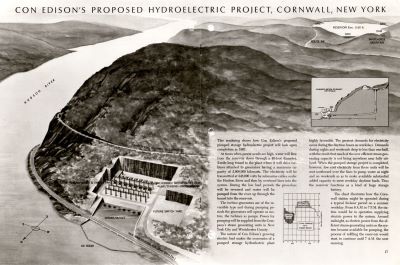

However, my mind was reminded not so much of the view itself but of threats to the view. The first example was from the proposed Storm King project by Con Ed. In 1962, Consolidated Edison applied to the Federal Power Commission for a license to construct a hydroelectric storage plant in the Hudson Highlands. The drawing of the proposed plant cut into the highlands became memorable in its own right. Just as the demolition of Penn Station spurred an historic preservation movement in New York, so to the proposed hydroelectric plant spurred an effort to preserve the scenic Hudson view and the creation of the organization Scenic Hudson.

A rather lengthy legal battle ensued which I will not recount here. What is relevant is that there is more to a construction proposal than cost. More than even the environment. There is something intangible: the view. That view belongs to people who do not own the land but whose right to enjoy the view of it needs to be taken into account.

Years later another power plant threatened the view. This time is a nuclear plant. And with no sense of irony, it was to be built in view of the home of Frederic Church whose Olana homestead was on the opposite side of the Hudson River. This time, Harvey Flad, Vassar College, who has presented in IHARE Teacherhostels/Historyhostels and made me aware of the issue, along with others took “visual preference surveys” to determine the preference of those people who would view the construction. The “no nuclear plant view prevailed. It changed the legal landscape as well.

The conflict divided the community and put neighbor against neighbor. On one hand, there were the people who wanted work. On the other, there were those who sought to preserve the historic view that drew Church to this location. In this situation, there is no pleasing everyone. Sometimes the conflict was class and geographic related. The newcomers to the community were attracted by the scenic view and did not want to lose it; the old-timers Locals, Natives, wanted jobs. The scenic viewers prevailed. According to the judgment:

Hudson relies on the area’s high quality of life, contributed to by the visual appeal of the area, its historic fabric and texture, its pastoral setting, and attractions such as its waterfront park and Olana as the basis for continued economic growth.

In the New York City example, the conditions are man-made. All the buildings involved leverage a previously unknown sight. Prior to the mainly 20th century, there was no vantage point comparable those offered by the skyscrapers. i.e.. buildings that touch the sky. With the 20th-century all that changed especially with the Empire State Building. So far, the fight for a scenic view has been confined to the Hudson Valley. It has not yet migrated as a legal doctrine into the urban world. Perhaps as more anorexic supertalls are built.

But there is another issue which needs to be raised. It is the desire of people to preserve an imagined pristine past. The Hudson River school painters were notorious for omitting the signs of modernity, like trains, that compromised the pastoral view they painted. Indigenous people are asked to remain authentic living according to traditional ways and not be compromised by the world of the present. This need to preserve an imagined idyllic past is part of who we are just as the ongoing effort to keep building. Sometimes the two can be reconciled: If you build it, he will come. But more often than not people and places are trapped in the past, a subject to which I will return in a future blog.

Are you familiar with the Texas Capitol View Corridors?

No. Thanks for pointing it out.

Thank you for this important and thoughtful read. The other day the Boston Globe had an article about the Boston skyline, but in regard to signage on towers.

Pamela Yameen

Page: 18

https://edition.pagesuite.com/html5/reader/production/default.aspx?edid=947c94e0-e9d6-4424-b9c6-ddd32d813153&pnum=18

The problem is certainly not unique to New York. It just so happens that I get the New York papers and it triggered some teacher programs I had run in the Hudson Valley.

A further complication you didn’t mention is the climate crisis. It is imperative that we quickly transform our energy infrastructure. Some components of a new decarbonized system will have undesirable visual impacts and some may have the potential to be actually harmful to some human and non-human communities. The window on dithering is nearly closed.

Great article. But one that should be discussed is the “value of a historic site that has been paved over”. What meaning does it hold? And what’s the value of a historic marker placed for convenience rather than a true location?

Good points. “Paved paradise and put up a parking lot.”

Peter, Thank you for this insightful blog. Scenery matters. Natty Bumppo knew it, so should we.

Excellent Peter.