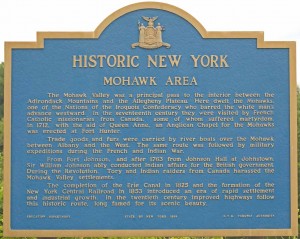

Peacefully sharing a space-time continuum does not come easily to our species. The challenge of doing so was played out in colonial New Amsterdam/New York in the 17th and 18th centuries especially from Albany and Schenectady westward throughout the Mohawk Valley.

There, and north to the Champlain Valley and Canada, multiple peoples who had not yet become two-dimensional cliches struggled to dominate, share, and survive in what became increasingly contentious terrain. Battles were fought, settlements were burned, and captives were taken, again and again.

By the 19th century, much of that world had vanished save for the novels of James Fenimore Cooper. By the 20th century, that world existed in state historic sites, historical societies and local museums, Hollywood, and at times in the state’s social studies curriculum.

That world consisted of a multiple casts of people who had known each other for centuries and who were meeting each other for the first time. The Iroquois and Algonquians were not strangers to each other when the Europeans arrived. The French and the English were long-standing rivals before they came to North America. In the 1600s, religious wars wreaked havoc on the European continent, especially in the land of the Palatines. New countries emerged as the Protestant Dutch wrested freedom from the Catholic Hapsburg. Irish, Scots, and Scotch-Irish were present as well. All these peoples would met, intermix, trade, fight, and negotiate in the world centered on the Mohawk (and Champlain) Valley in conflicts both local and global. Even as New Amsterdam/New York emerged as the unofficial capital of America, and then the world, upstate was engaged in its own effort to become a melting pot of a mixed multitude of peoples.

In the end, there were many losers. All the European colonizers, the British, the Dutch, and the French, with all their shifting alliances, intrigues, campaigns gave way to a new political entity. The jockeying of position from South Carolina to Canada, from the Mohawk Valley to the Ohio Valley by the Iroquois, Algonquians, and other Indian people was replaced by Trails of Tears, reservations and quasi-national status as a betwixt-and-between people who had been severed from their land.

Was another way possible? William Johnson liked to think so. We are more familiar with the literary world James Fenimore Cooper created than the actual world William Johnson lived. The Irish fur trader and merchant arrived in the region in 1738, served from 1746 to 1751 as New York’s Indian agent, and became Britain’s first Superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1755. He married Mary Brant, and opened his home to Indian people. Johnson has been described as “uniquely able to bridge the multiple cultures of the Mohawk Valley. His European-style household was an international crossroads for Irish, Dutch, German, English, and Native American travelers, politicians and settlers.”

That description comes from a brochure for the 2007 Western Frontier Symposium: Agents of Change in Colonial New York – Sir William Johnson’s World. One symposium presenter called him “our larger-than-life legend of the early American frontier,” while another castigates “scholarly infatuation with Johnson” at the expense of others.

Amidst the constant swirl of peoples, trade, diplomacy and war, Johnson loomed larger than others. His presence and diplomacy reached from Niagara to Lake George and beyond. Historian Timothy J. Shannon says, “Johnson spoke to the Indians in their own way in actions and appearances as well as words.” Shannon believes that Johnson understood that gifts, especially of clothing, were a tangible symbol of reciprocity and friendship between different peoples. Despite a frequent lack of financial support from the British political powers, Johnson recognized the importance of ceremonial presentations as a way to bridge the gap between two peoples. (See Timothy J. Shannon, “Dressing for Success on the Mohawk Frontier: Hendrick, William Johnson, and the Indian Fashion” William and Mary Quarterly 53 1996:13-42)

Ultimately, no matter how skillful he was, Johnson’s efforts were unsuccessful. The Iroquois struggle to preserve its land and way of life amidst competing colonial armies was was also unsuccessful. Eventually, the sheer numbers of new settlers made it impossible to remain viable as culturally distinct peoples in a comparatively small area.

There is much to be learned from the experiences of the mixed multitudes in the Mohawk Valley during the colonial era. The Salem Witch trials weren’t the only thing that happened between the settling of the colonies and the birth of the nation. Real people risked their lives in the real world that we overlook or minimize. The Mohawk Valley became part of a global battle for power when Europeans settled this land. The conflicts in that valley became part of New York, American, and global history.

The struggle of different peoples today to peacefully share a land, a region, a nation, and a planet continues to dominate the news. While New York’s youth may be more familiar with the history of Middle Earth than the Mohawk Valley, the challenges the people of the colonial era face remain part of our world. We would be wise to walk in the ways of the peoples of the Mohawk Valley, to remember their actions, and to learn from our history.

I think it is also important to note that Sir William Johnson, as demonstrated by Gregory Evans Dowd in his WAR UNDER HEAVEN: PONTIAC, THE INDIAN NATIONS & THE BRITISH EMPIRE (2002), amassed a huge land empire in the Mohawk Valley at the expense of the Six Nations while purporting to be their friend and patron. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix stands out as an example of his duplicity.

The Treaty of Stanwix will be covered in my post on “The Birth of the Nation (Part I).