South Carolina and slavery have been in the news. The former because the former governor of the state and now presidential candidate muffed a softball question where the latter was the answer. She may have been thinking she was campaigning in the Confederacy and not in the Union. One can’t help but wonder how many people from those small New Hampshire villages and hamlets died in the very war that was the subject of the question.

So instead of easily answering the question about the causes of the Civil War, she instead babbled. She ended up sounding like a college president from Harvard, MIT, and Penn having to answer a question about the call for genocide against Jews being an anti-Semitic act.

One should keep in mind that the very state she governed was the epicenter for slavery in the United States. Unfortunately, The New York Times 1619 Project has transformed a onetime comparatively minor event in Virginia into the starting point of America’s original sin and thus deprived South Carolina of its rightful place where systematic chattel slavery and racism began.

The other mainland British colonies stumbled into slavery. They were not founded by people who had the goal of creating a slave colony. The Carolinas were different. They may be why they are glossed over in the colonial founding stories. All the great tourist sites and stories for British and Dutch colonization here belong elsewhere.

As a reminder of the importance of South Carolina in the development of slavery in the British mainland colonies, below is the blog I wrote on Barbados, American Slavery and Racism. South Carolina was the colony of a colony and that colony was Barbados. We just celebrated the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party. The tea came from China.No civilized person could drink tea or coffee without sugar. When the American Revolution began, the mainland British colonies were not joined by their British counterparts. One reason is that those colonies were not settled for freedom of religion or any other kind of freedom. They were settled to produce sugar (rum and molasses). That meant constantly renewed slave labor force. When the American Revolution did occur, that meant the British Caribbean colonies were more valuable to the Crown than the mainland colonies were.

While becoming President of the United States does not require any expertise in American history — obviously — perhaps the former governor of South Carolina will spend some time and effort learning about the history of her own state especially if she wants to be President during the 250th anniversary of the birth of the country in 2026.

Barbados, American Slavery and Racism

August 1, 2023

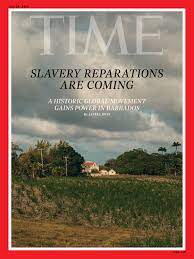

Barbados was the feature of a seven-page article in the July 24, 2023, issue of Time Magazine (print). That is a fairly substantial article for the mostly weekly magazine. The subject of the article as the subtitle stated was “How the tiny island of Barbados became a leader in the global push for reparations.” True to the subtitle, the article addressed precisely that issue. It traced the history of the island and the efforts of the people to obtain reparations. It was not about the United States slavery and racism.

That being said, there are several points of the article which nonetheless have direct bearing on the United States even without mentioning it.

1. British settlers first arrived in 1627.

To put that in American perspective, that is 20 years after the settlement at Jamestown, seven years after the arrival of the Pilgrims, three years after the Dutch settled New Amsterdam, three years before the Puritans arrived in Massachusetts Bay Colony, and 55 years before the Quakers arrived in Pennsylvania.

Barbados was then part of the British colonial settlement. In the 1600s. As Americans, we need to remove our geographical blinders and include the island in the study of early British colonialism here. It would be an island British Loyalists fled to at the end of the American Revolution because it was not one of the colonies which choose to rebel.

2. By the 1640s, Barbados was a sugar cane powerhouse.

Sugar production generated huge profits. The modern counterpart would not be oil in Saudi Arabia but cocaine. Barbados produced what Europeans had to have even though they had no biological need for it. Barbados was a drug powerhouse of the first order. And it was legal.

The economic dynamics of the island was vastly different from the mainland colonies mentioned above. None of them could match the economic importance of Barbados. One could try to cash in on it by supplying non-sugar products to the island since land was too precious to waste on them. Arguably, when Britain had to decide which was more important during the American Revolution the answer was Barbados.

3. The enormous profits inspired the world’s first slave codes, legislated in Barbados in 1661.

In 1619, there was no legally category of slaves in Virginia law or in British law. In 1626, the same was true in New Amsterdam under Dutch law. The Barbados slave code then became the model for slave codes throughout the British Atlantic colonies.

The demographic situation in Barbados was quite different from the mainland colonies. The trickle of Africans arriving in the latter paled in significance before the numerical need for workers in Barbados. Not only did this one small island dwarf the need for workers in the mainland colonies at any one time, due to disease and short-life spans, the need to steadily replenish the worker stock ensured a constant contact with Africa.

The numbers also told a different racial story. Yes, it was true that all the mainland colonies had African slaves but the differential in numbers was vast. In the northern colonies in particular, white people (somewhat of a historically inaccurate term in the 1600s) knew they were in the majority. In Barbados, the opposite was true. It was bluntly obvious to everyone that the number of people from African exceeded the number of people from Europe.

One may begin to glimpse here the racial divide that continues to this very day. The Africans, fresh off the boat, were black. They were not the wide range of hues encompassed by the term “Black” in the United States today. Today one may play guessing games with famous figures as to their racial background. There was no room for doubt in Barbados back in the 1600s. Everyone knew which side of the color line one was on, which color meant “slave,” and which person was bound by the slave codes.

SOUTH CAROLINA

At this point, one may be wondering what Barbados has to do with the United States. If you look again at the mainland colonies from the 1600s, you will notice one gaping absence – the Carolinas. The colony was founded in 1663 (not settled) under the direction of Charles II in the Restoration in Britain. It then became known as “the colony of a colony.” Barbados has been called “Little England” because it was so thoroughly English. That was true for white people. Those traditions carried over into South Carolina

While the other mainland colonies consisted of people who sailed here directly from Europe, many of the early settlers in South Carolina arrived via Barbados. People settling in the other mainland colonies did not arrive with the intention to create plantations of slaves producing sugar. … or any part of that description.

By contrast, people arriving in South Carolina were fully conversant with the plantation system where Africans were slaves, Europeans were free, and harsh slave codes were necessary to keep the peace. South Carolina, like Barbados, was an African-majority population.

One should keep in mind that it was not only White people who migrated to South Carolina. Some brought their African slaves with them. The latter too knew the plantation system.

Slavery was a significant part of the South Carolina economy right from the start. It was part of the colony’s DNA. The same cannot be said for the Chesapeake colonies or the north. Slavery took time to grow in numbers and never attained the percent of the population in South Carolina. Truly it may be said that Puritan New England and Little England Barbados belonged to two different cultural worlds, a difference that continues to divide the United States to this very day.

So whereas the settlers in Virginia 1619 or New Amsterdam in 1626 had to go through the process of deciding what exactly constituted a “slave,” the South Carolina settlers in the 1670s had no such issues. Everything had been worked out already in Barbados. It was simply a question of migrating the Barbadian way of life to the new colony.

CONCLUSION

In a blog, one cannot tell the full history of either Barbados or South Carolina or their connection in the 1600s. Yet it is enough to see that South Carolina was distinctly different than the other mainland British colonies in it its culture, demographics, racial values, and economy. With the other colonies, one traces their roots back to England of Holland. With South Carolina, one traces its roots to Barbados.

Even though in many ways, Barbados resembled Mother England, that was a Mother England without the vast drug profits from sugar and the constantly replenished African worker to harvest and process it and who were in the majority of the population. It is in Barbados that we find the development of race dividing people into Africans who were black and English who therefore must be white. It is in Barbados that we find the equation of black Africans with slavery. It is in Barbados that we find harsh slave codes to control the Africans and maintain the boundaries between the English and the African. And it is from Barbados that these values passed into the British mainland colonies to create the racial system that defined the Confederacy and the country to this very day.

SOURCES (Articles only)

Bull, Kinloch, “Barbadian Settlers in Early Carolina: Historiographical Notes” in South Carolina Historical Magazine 96/4 1995:329-339.

Burnard, Trevor, Games, Alison, ed., “Sugar and Slaves after Fifty Years,” in Early American Studies 20:4 2022:549-773 (multiple articles).

Dunn, Richard S., “The English Sugar Islands and the Founding of South Carolina,” in South Carolina Historical Magazine 72 1971:81-93.

Greene, Jack P., “Colonial South Carolina and the Caribbean Connection,” in South Carolina Historical Magazine 88/4 1987:192-210.

Greene, Jack P., “Changing Identity in the British Caribbean: Barbados as a Case Study,” in Colonial Identity in the Atlantic World, 1500-1800, Nicholas Canny and Anthony Pagden (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 213-266.

Harlow, Vincent T, A History of Barbados, 1625-1685, book review by Robert E. Park, The American Journal of Sociology 33 1928:669-670.

Harlow, Vincent T, A History of Barbados, 1625-1685, book review, unnamed, The Journal of Negro History 13 1928:102-103.

Harlow, Vincent T., A History of Barbados, 1625-1685, book review by Frank Pitman, The American Historical Review 33 1927:165-167.

Menard, Russell, “Slave Demography in the Lowcountry, 1670-1740: From Frontier Society to Plantation Regime in South Carolina Historical Magazine 96/4 1995:280-303.

O’Malley, George E., “Beyond the Middle Passage: Slave Migration from the Caribbean to North America, 1619-1807,” in William and Mary Quarterly 3rd Series 66/1 2009:125-172.

Roberts, Justin, “Surrendering Surinam: The Barbadian Diaspora and the Expansion of the English Sugar Frontier, 1670-75,” in William and Mary Quarterly 3rd Series 73/2 2016:225-256.

Roberts, Justin, and Beamish, Ian, “Venturing Out: The Barbadian Diaspora and the Carolina Colony, 1650-1685 in Creating and Contesting Carolina: proprietary era histories, Michelle LeMaster and Bradford J. Wood, ed. (Columbia: South Carolina: The University of South Carolina Press, 2013), 49-72.

Thomas, Jno. P. Jr., “The Barbadians in Early South Carolina,” in The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 31/2 1930 75-92.

Thompson, Peter, “Henry Drax’s Instruction on the Management of a Seventeenth-Century Barbadian Sugar Plantation,” in William and Mary Quarterly 3rd Series 66/3 2009:566-604.

Waterhouse, Richard, “England, the Caribbean and the Settlement of Carolina,” in Journal of American Studies 9/3 1975:259-281.