The Battle of Kadesh:

Meaning for Israel and the Bible

Paper presented November 16, 2023

Annual Conference of ASOR

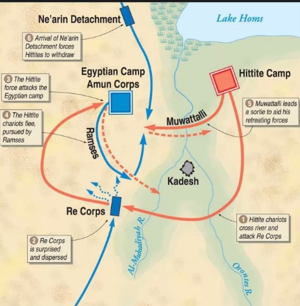

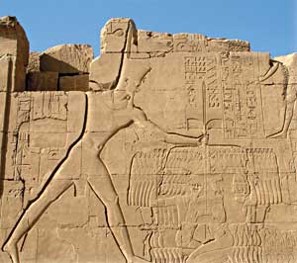

The Battle of Kadesh in year 5 of Ramses II between Egypt and the Hittites is one of the best documented battles in the ancient Near East. Records of the battle exist in multiple copies and formats throughout the land of Egypt including in giant billboard color. By now Egyptologists know that these accounts should not be taken as gospel. Instead they are royal propaganda by a king who did not win the confrontation.

This paper takes the position that there are specific elements in the Kadesh battle report that can be identified as contributing to the royal spin. These elements do not reflect historical events even though they give appearance of doing so. By examining these incidents and motifs, it is possible to determine if there is a pattern to them or their message. In other words, they do not exist by chance. Quite the contrary, they reflect a conscious decision by Ramses and are directed towards the audience who would read, see, and hear, about the battle in these reliefs distributed nationwide. They reveal the historical context not in which the battle was fought in year 5, but the subsequent context in which that battle was spun. Some of the incidents and motifs in these versions have direct bearing on both the history of Israel and the writing of the Hebrew Bible.

SLIDE Question #1: How Do We Know the Battle of Kadesh Occurred?

What is the archaeological evidence that proves that the Battle of Kadesh occurred?

Is there a destruction level at Kadesh that can be definitively attributed to this confrontation between these two ancient superpowers, the Hittites and the Egyptians?

Are there battlefield artifacts that can be assigned to both sides? A mound of chariots?

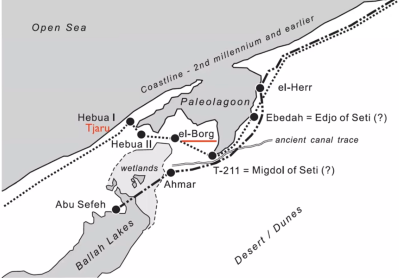

There is archaeological evidence for a campaign route from Egypt part of the way to Kadesh, the Way of Horus, but not the entire way. Is there evidence of a comparable route for the Hittites and their presumed allies? Let’s put this in context. Suppose over three thousand years from now there was proof of an airport in this city and an Interstate highway with rest stops to this location. Would that prove that on a specific date, you travelled it to attend this specific conference?

The general answer is “No.” There is no archaeological proof that a battle occurred in Ramses Year 5 between Egypt and the Hittites at Kadesh. Somehow an armed force of 20,000 plus support people and including horse and chariot marched hundreds of miles across Sinai and Canaan into Syria where it confronted a roughly comparably sized Hittite foe with both sides leaving no artefactual trace for archaeologists to discover. Good thing the only record of the battle wasn’t in the Hebrew Bible otherwise who would believe it happened.

SLIDE Question #2: Why Are there so many textual and relief records of the battle in Egypt?

No incident in Egyptian history is so impressed upon the mind of the traveler in Egypt as this battle between the forces of Ramses II and those of the Hittites at Kadesh on the Orontes, in the fourteenth century before Christ [now dated to the thirteenth century]. The young king’s supreme effort to save himself and his army from destruction is so often depicted and in such graph pictures upon the walls of the great temples, that no visitor, not even the most blasé “globe-trotter” can ever forget it (James Henry Breasted, The Battle of Kadesh: A Study in the Earliest Known Military Strategy, 1903 4).

The main source of information for the Battle of Kadesh consists of texts and reliefs found in Egypt. There are a plethora of such sources to be found throughout the country. These locations include: Abu Simbel, Abydos, Karnak, Luxor, and the Ramesseum. There are so many records that Egyptologists differentiate them into the Poem and the Bulletin, two sources about the same event with the relief captions providing another source. Egyptologists examine these different versions the way Biblical scholars investigate different textual versions of the same passage.

Instead of wrestling with the multiple versions of the Battle of Kadesh to create an historical reconstruction, let’s pause, take a deep breath and stand back and ask why are there so many versions of precisely the same battle?

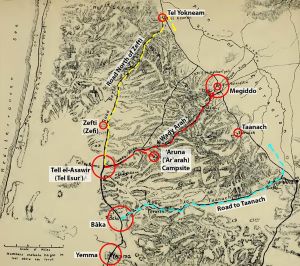

For example, how many records of Thutmose III at the Battle of Megiddo in the 15th century BCE are there?

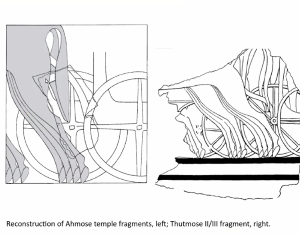

The legacy of battle reliefs can be pushed back to Pharaoh Ahmose against the Hyksos in the 16th century BCE from the excavations at Abydos by Steve Harvey.

Almost all the great warrior kings of the 18th, 19th, and 20th Dynasties, are consistent in the campaign reliefs they created for their battles – one set of reliefs at one location. Ramses is the anomaly. So even without delving into the weeds to historically recreate the Battle of Kadesh based on multiple texts and reliefs in the first place, it is legitimate to wonder why there are so many versions of the one battle and why are scattered throughout the land?

Question #3: What Does It Mean to Call the Ramses II record royal propaganda?

Given this abundance of textual and visual evidence, what does it mean to call it royal propaganda? What are the elements, motifs, and portions of the record that would cause one to identify the record as propaganda? I am using the term in the sense of spin. Spoiler alert. I hope I am not disclosing any information not already known to you.

The crux of the matter appears to be in a society of Pharaoh smites the enemy, when an Egyptian king actually did fight an enemy king, and not just some mayor of a Canaanite city, he did not smite the enemy. In fact, Ramses did not even win the confrontation with the Hittites.

Furthermore everyone who participated in the battle knew that Ramses did not smite the enemy. I suggest, based on the nationwide distribution of reliefs, that knowledge of this failure by Ramses similarly was widespread as well. Hence the need to spin the story and to ensure the spin was made known throughout the kingdom.

In this paper, I wish to suggest three ways in which Ramses spun the story. There are three events in the Battle of Kadesh inscriptions that look like they could be historical but which never happened. They are:

1. he was led astray by the Yahweh-worshipping Shasu – Thutmose III made a bold decision at Megiddo and was successful. He was a great leader. By contrast, Ramses’s bold decision before he arrived at Kadesh did not work out so well. But he was not responsible for the failure. How better to explain his failure than to blame a wilderness people of chaos? Isn’t the failure to restore or maintain ma’at normally attributed to these forces of chaos? Why should scholars even assume this event occurred? Would you with a biblical spy story? When Seti fought the Shasu were they in Syria? Shouldn’t the Shasu be in wilderness east of Egypt?

2. he was deserted by his troops – Seriously!!!! People who had fought under the command of Seti and in his own earlier campaigns, now deserted Ramses after marching with him for hundreds of miles away from home! Why take this claim seriously? This charge raises a topic typically ignored by biblical scholars: the role of the military in Egypt during the 19th Dynasty particularly in the time of Ramses.

His capital city was a military one. Power had shifted from the priests in Thebes to the generals in Avaris. The military was in ascendancy. The capital culture was mixed or hybrid. The 19th Dynasty royal family was from the northeast Delta; its precise connection to the Hyksos whom Seti honored at an event and Ramses later commemorated remains unknown. The armed forces were multi-racial and multi-ethnic. The young king needed to earn their loyalty especially if there was an alternative to his leadership. The military knew it had not deserted the king in battle, yet he publicly claimed they had. Ramses’s accusation of a great crime by the military was a post-Kadesh effort to assign blame later offset by his attempt instill loyalty in them with his 400 Year Stela. He was not deserted at Kadesh. Perhaps he had been deserted later somewhere later when the army stood down and did not interfere with a challenge to him.

3. he prayed to Amun – his lengthy well-crafted prayer to his father deity did not occur on the field of battle; this expression of personal piety would have been well-known to the audience he was trying to con. Ramses stood alone, triumphing over the enemy while his supposed supporters watched. One can almost hear him saying:

Stand still, and see the salvation of the Amun, which he will shew to you to day: for the Hittites whom ye have seen to day, ye shall see them again no more for ever (based on Ex. 14:13).

Neither Thutmose III nor Seti I ever seemed to have needed such a prayer when in combat.

One may add, how did the naar feel after rescuing their king and not getting the recognition they deserved since Ramses triumphed on the battle field all by himself?

I suggest that these items are not historical from the Battle of Kadesh inscriptions. Nor are they simply spin conjured up out of thin air. Instead they reflect the needs of the king in the aftermath of the Battle he had lost. They derive from another confrontation where he had to explain his defeat where the military did not support him, where his foe was allied with Yahweh-worshiping wilderness people, and his foe had prayed for his father deity to divinely intervene in history.

Question #4 The Song of the Sea and the Battle of Kadesh

Speaking of the Song of the Sea, now consider Joshua Berman’s scholarship on it in relation to Ramses II at Kadesh. Berman has carved out a niche for himself over the years in asserting the interrelationship between Ramses and the Song of the Sea as shown here.

2014 SBL Conference “The Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses II and the Song of the Sea”

2015 SBL Conference “Juxtaposed Conflicting Compositions: A New Kingdom Egyptian Parallel”

2015 Mosaic article “Was there an Exodus?”

2016 JNSL article “Juxtapose Conflicting Compositions: A New Kingdom Egyptian Parallel”

2016 Book chapter “The Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses II and the Song of the Sea Account (Exodus 13:17-15:19) in “Did I Not Bring Israel Out of Egypt?”: Biblical, Archaeological, and Egyptological Perspectives on the Exodus Narratives (James K. Hoffmeier, Alan R. Millard, and Gary A. Rendsburg, ed.)

2017 Book chapter “The Exodus Sea Account (Exod 13:17-15:19) in Light of the Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses II” in his book Inconsistency in the Torah: Ancient Literary Convention and the Limits of Source Criticism

2017 Book chapter “Diverging Accounts within the Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses II” in his book Inconsistency in the Torah: Ancient Literary Convention and the Limits of Source Criticism.

The details of this proposed relationship between the Song of the Sea and the Kadesh Inscriptions are not the issue here. The methodology is. The relevance is in the use of the Egyptian literary texts and reliefs as part of the discussion about the historicity of the Exodus. The typical approach to examining the archaeology of the Exodus omits this area of study. If minimalists wish to deny a connection by postulating a late date for the composition of the Song of Sea that somehow by chance is consistent with imagery and motifs used by Ramses II, they are, of course, free to do so. They also can reject the alleged parallelisms proposed by Berman.

Suppose now one were to take Berman’s analysis one step further. Suppose instead of simply postulating a borrowing from Ramses by Israel, consider applying a “Na’aman” reversal to the process. He among others have proposed that Canaanites in Canaan experiencing Egyptian imperialism and slavery celebrated the Egyptian departure from Canaan at the end of the Late Bronze Age which subsequently was transformed into the Exodus story. Israel didn’t go forth, Egypt did. Let’s try a similar reversal here. Did Ramses borrow from or respond to the Exodus in his portrayal of the Battle of Kadesh? The question at least deserves to be explored as a legitimate alternative explanation for the Exodus.

I submit these portions of Ramses’s song of victory at the waters of Kadesh derive from his recent failure in the Exodus following shortly after his failure at Kadesh. Knowing that helps resolve the conundrum of determining of when a purported Exodus could have occurred given the Egyptian timeline.

Question #5 When Could the Exodus Have Occurred?

One approach to rejecting the validity of an historical Exodus is to document that there is no place in Egyptian history where it could have happened. This effort to demonstrate the absence of any such time has been critical to the work of Lester L. Grabbe.

2000 “Adde Praeputium Praeputio Magnes Acervus Erit: If the Exodus and Conquest Had Really Happened…” in Virtual History and the Bible, ed. J. Cheryl Exum

2010 “From Merneptah to Shoshenq: If We Had Only the Bible…” in Israel in transition: From Late Bronze II to Iron IIA (C. 1250-850 BCE) Volume 2 The Text which he edited along with Volume 1 The Archaeology (2008)

2014 “The Exodus and Historicity” in The Book of Exodus: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation, eds. Thomas Dozeman, Craig Evans, and Joel Lohr

2016 “Late Bronze Age Palestine: If we had only the Bible…” and “Canaan under the Rule of the Egyptian New Kingdom: From the Hyksos to the Sea Peoples” in The Land of Canaan in the Late Bronze Age, ed. Lester Grabbe

First he (2014) states that there is nothing in the Egyptian texts that could be related to the story of the Exodus. Nothing in the second millennium BCE suggests a series of plagues, death of children, physical disruption of the country, and loss of huge numbers of its inhabitants. By his reasoning since it is unlikely that a bellowing hippopotamus in Thebes disturbed the sleep of Apophis in Avaris hundreds of miles away that therefore the Quarrel Story of it happening must also be of zero historical value. Disproving the physically-literal interpretation of biblical texts is irrelevant to determining if the Exodus occurred. He knows that the search for naturalistic explanations for the plagues misses the point because he says so himself (2010:67). He knows the plague stories are to deliver a message. So why raise that point that plagues can’t be found in Egypt as part of a proof that the Exodus could not have occurred if you know they are symbolic?

Better to try to understand what message Sekhmet and the plagues delivered within the Egyptian cultural context than to debate the historicity of the goddess or the occurrence of the plagues.

He spends 46 pages (2016) on an analysis of the Exodus as an event in history. He covers a great deal of ground both physically and topically. Many peoples, places, (time)periods, scholars, and definition of terms are included. His effort suggests a person who is trying to be fair, comprehensive, and thorough into his investigation into whether or not an historical Exodus occurred. Still one does wonder how many people would have to have left Egypt in open defiance of Ramses or any other Pharaoh to constitute an Exodus. More than two? Less than 600,000?

He is dismissive of an historical Exodus in the time of Ramses. His analysis of the reign of Ramses itself is his comment that identifying him as the Pharaoh of the exodus “is rather strange considering that far from being destroyed, Egypt was at its height under his reign!” (2016:55) He had said the same in Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? 2007:59). In a table of Egyptian kings at the end of his chapter “Canaan under the Rule of the Egyptian New Kingdom,” he lists Ramses with the description “one of the greatest Pharaohs; an unlikely ruler for the exodus! (2016:101)” But does that perception accurately reflect the conditions which existed after the young ruler failed at Kadesh? He, like many Egyptologists, is a victim of the Ramses spin.

Consider this alternate view of Ramses II by the Egyptologist Kara Cooney.

Strangely, Grabbe himself provides the information for an Exodus in the time of Ramses without realizing it. He writes that there were very few periods during the Late Bronze Age when Canaan was not firmly under Egyptian control (2016:99). He claims his survey indicates one of the main difficulties with the concept of an historical Exodus: “THERE IS NO ROOM FOR SUCH AN EVENT DURING THIS TIME” (2016:99; capitalization added). Furthermore, as he stated the page before:

Strangely, though, it is often proposed that the exodus and/or conquest of Canaan by the Israelites took place under his reign – apparently overlooking that he was one of the strongest of the Pharaohs who had firm hold of the whole region well into the Syria and reigned for so much of the thirteenth century (2016:98).

Yet a few sentences earlier he had written that following the failure at Kadesh by the strong Pharaoh, the “result was that Palestine (meaning Canaan) rebelled against Egyptian rule” (2016:98).

Why didn’t red lights blare, sirens shriek, and bells ring when he wrote that? Canaanites in the land of Canaan saw the weakness of the “strong” Pharaoh after Kadesh and rebelled while Canaanites in the land of Goshen remained silent! Egyptologists recognize that the very people who fought at Kadesh knew the truth of the battle. Ramses could not deceive them with his account. Canaanites in the military including Hyksos knew what Canaanites in the land of Canaan knew. This was the moment to rebel. This was the moment for a charismatic military leader popular with the troops to seize the opportunity to confront Ramses the failure Pharaoh and lead the Exodus.

Ramses after the Battle of Kadesh was not yet the ultimate Pharaoh, to borrow the title of Egyptologist Peter Brand’s new book.

The time between his failure at Kadesh in year 5 and his royal proclamations of Kadesh glory and his crackdown in Canaan beginning in year 8 provided a window of opportunity for a military figure to challenge the vulnerable and exposed king. That’s when the Exodus occurred. There is room in the Egyptian timeline for an Exodus in the time of Ramses. Is there room in biblical scholarship?

Conclusion

Ramses’s versions of the Battle of Kadesh is a prime example where an ancient source should not be taken as gospel.

Grabbe writes, “Historicity can be determined only when all possibilities have been considered” (2014). I submit that he has not considered them all. To answer the question of whether or not an historical Exodus occurred, one needs to engage the reign of Ramses II especially following his failure at Kadesh.

Grabbe writes “The Moses story shows ‘growth rings’ which indicate a development that drew on the Jeroboam tradition in order to develop the biblical like of Moses” (2010:228). The truth is the other way of around. The tree of the Exodus story began in the Exodus and it is the attempt to portray Jeroboam as a new Moses that drew on it.

“Moses led people out of Egypt against the will of Ramses II (1279-1213 BC) on the seventh hour of New Year’s Eve at the end of Ramses’s seventh year of ruling. It is an Egyptian story.”

That is the speculative historical reconstruction I propose in the opening sentences to my book The Exodus: An Egyptian Story.

To understand Ramses’s records of the Battle of Kadesh, one must recognize that his failure there provided the opening for the Exodus to occur.