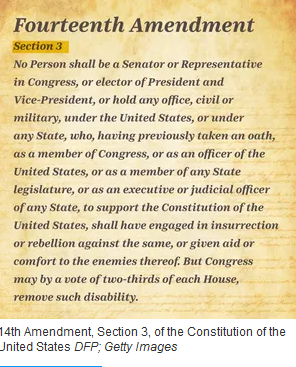

The current issue of Biblische Notizen (193, 2022) contains a series of articles about the confrontation in biblical scholarship between the biblical “minimalists” and the “maximalists.” The opening article by Lester Grabbe is entitled “How the Minimalists Won! A Discussion of Historical Method in Biblical Studies.” In it he claims not be a minimalist himself but declares in the opening paragraph:

Some will be surprised to hear that the Minimalists have won the battle in the struggle over history and the Bible….This paper discusses how, and especially why we are presently (almost) all minimalist, and why they should now cease to fight that battle.

In this article, Grabbe mentions two historical events to illustrate his points: the Mesha Stele and Sennacherib’s invasion of Judah in 701 BCE.

In his own work, the Exodus that has been a topic of great interest to him. A partial list includes:

2000 “Adde Praeputium Praeputio Magnes Acervus Erit: If the Exodus and Conquest Had Really Happened…” in Virtual History and the Bible, ed. J. Cheryl Exum

2010 “From Merneptah to Shosheng: If We Had Only the Bible…” in Israel in transition: From Late Bronze II to Iron IIA (C. 1250-850 BCE) Volume 2 The Text which he edited along with Volume 1 The Archaeology (2008)

2014 “The Exodus and Historicity” in The Book of Exodus: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation, eds. Thomas Dozeman, Craig Evans, and Joel Lohr

2016 “Late Bronze Age Palestine: If we had only the Bible…” and “Canaan under the Rule of the Egyptian New Kingdom: From the Hyksos to the Sea Peoples” in The Land of Canaan in the Late Bronze Age ed. Lester Grabbe

In the first publication, Grabbe (2000) has a great deal of fun imagining what would have happened if an Exodus of 600,000 men had occurred. He continually mocks the biblical story by presenting the absurdities which would have resulted in an Exodus of millions of people, their animals, and the loot from despoiling the Egyptians. How could tiny Edom think of refusing such an enormous force passage through the land? How could the Canaanites have resisted such an occupying army? Think of the mighty empire, Israel could have created long before Assyria, Babylonia, Persia, Alexander, and Rome with a population of that size!

What if Grabbe had decided to be a scholar instead of being content to ridicule the physically-literal interpretation of the biblical text? For example, Grabbe writes about the reputation this massive force of 600,000 would have had. It would have overwhelmed any who dared to stand it its way. Suppose instead, he had mentioned:

And when the Philistines heard the noise of the shouting, they said, “What does this great shouting in the camp of the Hebrews mean?” And when they learned that the ark of Yahweh had come to the camp, the Philistines were afraid; for they said, “A god has come into the camp.” And they said, “Woe to us! For nothing like this has happened before. Woe to us! Who can deliver us from the power of these mighty gods? These are the gods who smote the Egyptians with every sort of plague in the wilderness. Take courage, and acquit yourselves like men, O Philistines, lest you become slaves to the Hebrews as they have been to you; acquit yourselves like men and fight” (I Sam. 4:6-9).

Then he might have pursued the issue of how did this reputation arise and what is the (military) meaning of the word Hebrew in this context.

He might have explored the violence of Levi and Simeon and inquired as to the origin of that tradition.

He might have explored the more reasonably-sized military forces of Gideon and David.

He might have explored the use of numbers and what the “thousands” mean in non-Exodus stories.

But Grabbe does not pursue these avenues of scholarship. Instead he just had fun at the expense of the physically-literal interpretation of the biblical text.

Even when the opportunity to investigate the Exodus is staring him right in the face, he is Balaam and cannot see it. Grabbe writes that if Israel had been as strong as implied by the numbers of fighting men, it could have taken control of at least Lower Egypt? Isn’t that what the Hyksos did? Grabbe’s comment that nothing in the Hyksos account by Josephus evokes Israel omits an analysis of the Hyksos in the 19th Dynasty (2014:81). If Grabbe had realized that there was a connection between the Hyksos and the Exodus, he also would have realized that there were references in the Egyptian records from the time of Ramses and Merneptah that should be explored in an historical reconstruction of the Exodus.

Grabbe (2014) subsequently states that there is nothing in the Egyptian texts that could be related to the story of the Exodus. Nothing in the second millennium BCE suggests a series of plagues, death of children, physical disruption of the country, and loss of huge numbers of its inhabitants. He neglects to mention that it is unlikely that a bellowing hippopotamus in Thebes disturbed the sleep of Apophis in Avaris hundreds of miles away and that therefore the story of it happening also is of zero historical value. Disproving the physically-literal interpretation of biblical texts is irrelevant to determining if Moses led people out of Egypt against the will of Ramses and constituted them in the wilderness as Israel or not. Grabbe knows that the search for naturalistic explanations for the plagues misses the point because he says so himself (2010:67). He knows the plague stories are to deliver a message. So why raise that point that plagues can’t be found in Egypt as part of a proof that the Exodus could not have occurred?

Grabbe considers it strange that there is not even a hint in Egyptian literature, iconography or legend of the Egypt stories in the Books of Genesis and Exodus. This is the precise dilemma I avoided in my book The Exodus: An Egyptian Story. Any attempt to create a historical reconstruction of the Exodus as an event of people leaving Egypt in open defiance of Ramses or any other Pharaoh inevitably leads to issues of biblical exegesis – when were texts written? By whom? For what purpose? Grabbe brings his biblical preconceptions to his analysis that undermines his effort to reconstruct the historical Exodus without his being aware of it. For example, to continue with his plague example, what are the cosmological plague traditions in Egypt, meaning what message did the Egyptians deliver through their plague myths? Based on that analysis one would then try to understand what message Israel sought to deliver through its version of the plague myths in rebuttal to the Egyptian cultural construct. The physical historicity of the ten plagues (except the last one) is not the issue. Grabbe’s search for the physical plagues in the Egypt record is comparable to the search for them by evangelicals. He is as much a literalist in disproving the Exodus as they are in proving it.

Grabbe (2016) here spends 46 pages on an analysis of the Exodus as an event in history. He covers a great deal of ground both physically and topically. Many peoples, places, (time)periods, scholars, and definition of terms like nomads and tribes are included. His effort suggests a person who is trying to be fair, comprehensive, and thorough into his investigation into whether or not an historical Exodus occurred. Still one does wonder how many people would have to have left Egypt in open defiance of Ramses or any other Pharaoh to constitute an Exodus. More than two? Less than 600,000?

Grabbe opines that no event of the size and extent to the Exodus could have failed to leave significant archaeological remains. One might also ask what are the archaeological remains in Canaan and Syria of Ramses’s army of 20,000? What is the archaeological evidence of the Shasu in the wilderness for centuries beyond Egyptian Pharaoh’s mentioning their existence? Without the texts, how would know that the Shasu existed or the large-scale Battle of Kadesh had been fought?

He concludes his analysis by organizing the data into the following sections:

Biblical data confirmed

Biblical data not confirmed though they may be correct

Biblical picture incorrect

Biblical picture omits/has gaps.

Grabbe employs a similar schematic in other publications as well as an illustration of his thoroughness and fairness in dealing with the question of the Exodus and biblical texts. His analyses always led him to believe based on the evidence that an historical Exodus did not occur: people did not leave Egypt in defiance of Pharaoh.

One critical question is given the assumption of no historical Exodus, how did it come to be that there is such an extensive story of the Exodus in the biblical narrative? How come it shows signs of being revised on multiple occasions delivering multiple messages?

Grabbe is enamored of the speculative hypothesis that Merneptah took Israelites captives in his 1207 BCE campaign. These slaves in Egypt were the source of the Exodus story whenever they returned to Canaan after Egyptian imperial rule collapsed or in the Iron Age. This speculative historical reconstruction is based on the premise that the Exodus did not occur, the biblical story does, therefore there has to be an explanation for how that happened.

A more popular explanation is a speculative historical reconstruction by Nadav Na’aman, “The Exodus Story: Between Historical Memory and Historiographical Composition” (JANER 11 2011:39-69). His theory, later supported by Ron Hendel, posits a reverse exodus. Instead of Israel going forth from Egypt, Egypt left Canaan. Na’aman is referring to the departure of Egypt after centuries of rule in the New Kingdom generally ending somewhere around 1139 BCE in the reign of Ramses VI. During that time people in the land of Canaan thought of themselves as slaves of Egypt and not slaves in Egypt. After Egypt withdrew, the people left in the land transformed the memory of that occurrence into the story of the Exodus from Egypt we know today.

Here is an example of another speculative historical reconstruction from a different perspective: the Song of the Sea (Ex. 15) was not composed as a single song. Instead it grew by stanza in response to different encounters between Israel and Egypt

Stanza 1 the Exodus showdown in the time of Moses and Ramses also known as the Song of Miriam

Stanza 2 Merneptah’s failure to destroy the seed of Israel in the time of Joshua and added at Mt. Ebal

Stanza 3 the defeat of the forces of Ramses III (Se-sera, Sisera) in the time of Deborah probably added at Mt. Ebal

Stanza 4 celebrating the withdrawal of Egypt by Ramses VI added at Shiloh.

This composite song was part of the Book/Scroll of the Wars of Yahweh (against Egypt) which served as a source document when the alphabet narrative prose account was written.

I submit that this speculative historical reconstruction is more plausible, more reasonable, more comprehensive, and more coherent than the reverse exodus hypothesis of Na’aman. It also addresses some on the concerns raised by Grabbe about the maintenance of the memory of the Exodus and the continuity of the Israel/Egypt relationship from the end of the Late Bronze Age into the Iron I period before becoming part of a prose narrative in Iron II.

Speaking of the Song of the Sea, now consider Joshua Berman’s scholarship on it in relation to Ramses II at Kadesh. Berman has carved out a niche for himself over the years in asserting the interrelationship between Ramses and the Song of the Sea.

2014 SBL Conference “The Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses II and the Song of the Sea”

2015 SBL Conference “Juxtaposed Conflicting Compositions: A New Kingdom Egyptian Parallel”

2015 Mosaic article “Was there an Exodus?”

2016 JNSL article “Juxtapose Conflicting Compositions: A New Kingdom Egyptian Parallel”

2016 Book chapter “The Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses II and the Song of the Sea Account (Exodus 13:17-15:19) in “Did I Not Bring Israel Out of Egypt?”: Biblical, Archaeological, and Egyptological Perspectives on the Exodus Narratives (James K. Hoffmeier, Alan R. Millard, and Gary A. Rendsburg, ed.)

2017 Book chapter “The Exodus Sea Account (Exod 13:17-15:19) in Light of the Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses II” in his book Inconsistency in the Torah: Ancient Literary Convention and the Limits of Source Criticism

2017 Book chapter “Diverging Accounts within the Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses II” in his book Inconsistency in the Torah: Ancient Literary Convention and the Limits of Source Criticism.

The details of this proposed relationship between the Song of the Sea and the Kadesh Inscriptions are not the issue here. The relevance is in the use of the Egyptian literary texts and reliefs as part of the discussion about the historicity of the Exodus which Grabbe does not do. The typical approach to examining the archaeology omits this area of study. If minimalists wish to deny a connection by postulating a late date for the composition of the Song of Sea that somehow by chance is consistent with imagery and motifs used by Ramses II, they are, of course, free to do so. They also can reject the alleged parallelisms proposed by Berman.

Suppose now one were to take Berman’s analysis one step further. Suppose instead of simply postulating a borrowing from Ramses by Israel, consider applying a “Na’aman” reversal to the process: did Ramses borrow from or respond to the Exodus in his portrayal of the Battle of Kadesh?

I submit the following portions of Ramses’s song of victory at the waters of Kadesh derive from his recent failure in the Exodus following shortly after his failure at Kadesh.

1. he was led astray by the Yahweh-worshipping Shasu – Thutmose III made a bold decision at Megiddo and was successful. He was a great leader. By contrast, Ramses’s bold decision at Kadesh did not work out so well. But he was not responsible for the failure. How better to explain his failure than to blame a wilderness people of chaos? Why should scholars assume this event occurred?

2. he was deserted by his troops – Seriously!!!! People who had fought under the command of Seti and in his own earlier campaigns, now deserted Ramses after marching with him for hundreds of miles away from home! Why take this claim seriously? This charge raises a topic typically ignored by biblical scholars: the role of the military in Egypt during the 19th Dynasty particularly in the time of Ramses.

His capital city was a military one. Power had shifted from the priests in Thebes to the generals in Avaris. The military was in ascendancy. The 19th Dynasty royal family was from the northeast Delta; its precise connection to the Hyksos whom Seti honored at an event and Ramses later commemorated remains unknown. The armed forces were multi-racial and multi-ethnic. The young king needed to earn their loyalty especially if there was an alternative to his leadership. The military knew it had not deserted the king in battle, yet he publicly claimed they had. Ramses’s accusation of a great crime by the military was a post-Kadesh effort to install loyalty as was his 400 Year Stela. He was not deserted at Kadesh, he was deserted at Goshen when the charismatic, popular, and superior military-leader Moses led people out of Egypt and the army stood down and did not interfere.

3. he prayed to Amun – his lengthy well-crafted prayer to his father deity did not occur on the field of battle; this expression personal piety would have been well-known to the audience he was trying to con. Ramses stood alone, triumphing over the enemy while his supposed supporters watched. One can almost hear him saying:

Stand still, and see the salvation of the Amun, which he will shew to you to day: for the Hittites whom ye have seen to day, ye shall see them again no more for ever (based on Ex. 14:13).

4. how did the naar feel after rescuing their king and not getting the recognition they deserved since Ramses triumphed on the battle field all by himself?

Muwatillis knew where the battle would be fought. He arrived there first.

Muwatillis knew where the waters were.

Muwatillis knew the route Ramses would take.

Muwatillis baited Ramses to charge into a trap.

The same strategy would work when leaving Egypt in defiance of the king.

Ramses’s versions of the Battle of Kadesh is a prime example where an ancient source should not be taken as gospel. I submit, it is possible not only to examine the Song of the Sea based on the Battle of Kadesh poems, bulletins, and reliefs, but possible to examine them as part Ramses’s response to a second failure following shortly after his first failure. In fact that is the speculative historical reconstruction I propose in my book The Exodus: An Egyptian Story.

Grabbe is dismissive of an historical Exodus in the time of Ramses. His analysis of the reign of Ramses itself is his comment that identifying him as the Pharaoh of the exodus “is rather strange considering that far from being destroyed, Egypt was at its height under his reign!” (2016:55; also used in Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? 2007:59). In a table of Egyptian kings at the end of his chapter “Canaan under the Rule of the Egyptian New Kingdom,” Grabbe lists Ramses with the description “one of the greatest Pharaohs; an unlikely ruler for the exodus! (2016:101)” But does that perception accurately reflect the conditions which existed after the young ruler failed at Kadesh?

Strangely, Grabbe himself provides the information for an Exodus in the time of Ramses without realizing it. He writes that there were very few periods in during the Late Bronze Age when Palestine (meaning Canaan) was not firmly under Egyptian control (2016:99). He claims his survey indicates one of the main difficulties with the concept of an historical Exodus: “THERE IS NO ROOM FOR SUCH AN EVENT DURING THIS TIME” (2016:99; capitalization added). Furthermore, as he stated the page before:

Strangely, though, it is often proposed that the exodus and/or conquest of Canaan by the Israelites took place under his reign – apparently overlooking that he was one of the strongest of the Pharaohs who had firm hold of the whole region well into the Syria and reigned for so much of the thirteenth century (2016:98).

Yet a few sentences earlier he had written that following the failure of the strong Pharaoh, the “result was that Palestine (meaning Canaan) rebelled against Egyptian rule” (2016:98).

Why didn’t red lights blare, sirens shriek, and bells ring when he wrote that? Canaanites in the land of Canaan saw the weakness of “strong” Pharaoh and rebelled while Canaanites in the land of Goshen remained silent! Egyptologists recognize that the very people who fought at Kadesh knew the truth of the battle. Ramses could not deceive them with his account. Canaanites in the military including Hyksos knew what Canaanites in the land of Canaan knew. This was the moment to rebel. This was the moment for a charismatic military leader popular with the troops to seize the opportunity to confront Ramses the failure and lead the Exodus.

Ramses after the Battle of Kadesh was not yet the ultimate Pharaoh, to borrow the title of Egyptologist Peter Brand’s forthcoming book. The time between his failure at Kadesh in year 5 and his royal proclamations of Kadesh glory and his crackdown in Canaan beginning in year 8 provided a window of opportunity for a military figure to challenge the vulnerable and exposed king.

Here are some questions Grabbe might have asked if he was seriously interested in pursuing the possibility of an historical Exodus in the time of Ramses.

Why did the adult Ramses insert himself as child accompanying his father on his campaigns? Why did he erase or “cancel” the person who actually had? This action was not standard operating procedure. It was personal.

What happened to the person Ramses erased? Did he disappear from history or discover a God in history?

Why did Ramses need to create so many portrayals of his battle at Kadesh? How many duplicate copies did Thutmose III, Seti, and Ramses III make of their battles? Is there anyone in the ancient world who made a greater effort to make his name great than did Ramses II at the Battle of Kadesh? Archaeologists love it when kings make their names great, but that was not the religion Moses created as part of his rejection of the Egyptian cultural construct.

Why did Ramses add the non-historical elements to his Battle of Kadesh reports noted above?

Why did Ramses need to gain the loyalty of the Hyksos who remained in the land of Goshen with the 400 Year Stele?

Grabbe should follow his own advice here.

The biblical text is indeed often unreliable, but so are primary sources in many cases.

Egyptologist Kara Cooney in The Good Kings: Absolute Power in Ancient Egypt and the Modern World (2021), takes Egyptologists to task for succumbing to the hype, spin, and propaganda of Egyptian rulers. In her opening chapter entitled “We Are all Pharaoh’s Groupies.” She states:

I work in a field of apologists who believe in an Egypt of truth, beauty, and power—and in many ways, I am still an adherent to my chosen faith…. I, myself, have been co-opted, unable to recognize the propaganda that the ancient Egyptians were creating.

She asserts that Ramses tried to convince the populace that he was truly what he said he was. Ramses appears to have successful not only with Egyptologists but with biblical scholars.

Cooney’s chapter about Ramses is subtitled “The Grand Illusion.” A subsection is entitled “Ramses the Gaslighter.” She describes him as a figure of optics not substance, of spin not achievement, of hyperbole and not accomplishment except to gaslight Egyptologists and biblical scholars. She asks: “What kinds of insecurities was this king hiding?” The answer is the Sun King lived in the shadow of the man Moses all his life.

Grabbe writes, “Historicity can be determined only when all possibilities have been considered” (2014). I submit that he has not considered them all. To answer the question of whether or not an historical Exodus occurred, one needs to engage the reign of Ramses II especially following his failure at Kadesh.

Grabbe writes “The Moses story shows ‘growth rings’ which indicate a development that drew on the Jeroboam tradition in order to develop the biblical like of Moses (2010:228). The truth is the other way of around. The tree of the Exodus story began in the Exodus and it is the attempt to portray Jeroboam as a new Moses that drew on it.

The histories of Israel need to be rewritten.

The commentaries on the origin of the Hebrew Bible need to be rewritten.

That is the minimum of what needs to be done.

See previous blogs:

Passover and Pharaoh Smites the Enemy February 19, 2022

Egyptologists, Biblical Scholars, and The Exodus March 10, 2022