Are you captain of your fate, master of your destiny?

Are you a victim of your hyphen?

Way back in September, The New York Times had on the front page of its Arts section, an article entitled, “Book Aims to Recast the Native Narrative: A Finnish historian argues against the American trope of the ‘doomed Indian.’”

That provocative title was for the just published book Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America by Pekka Hämäläinen, University of Oxford. The goal of the book is to transform the story of the four-hundred years war between Europeans and Americans versus Indians from one where the latter are victims to one where they powerful actors who profoundly shaped the course of events.

Hämäläinen’s goal is to re-envision the American grand narrative at least for the early years. According to the article, his “first book, “The Comanche Empire,” offered an exhaustively researched and strikingly new interpretation of the nomadic group that dominated the Southwest from about 1750 to 1850 (and Hollywood westerns for much of the 20th century), but remained relatively unstudied by scholars.”

To do so, he drew on his own books on the Lakota and Comanche including “hoof-pounding accounts of battles on horseback.”

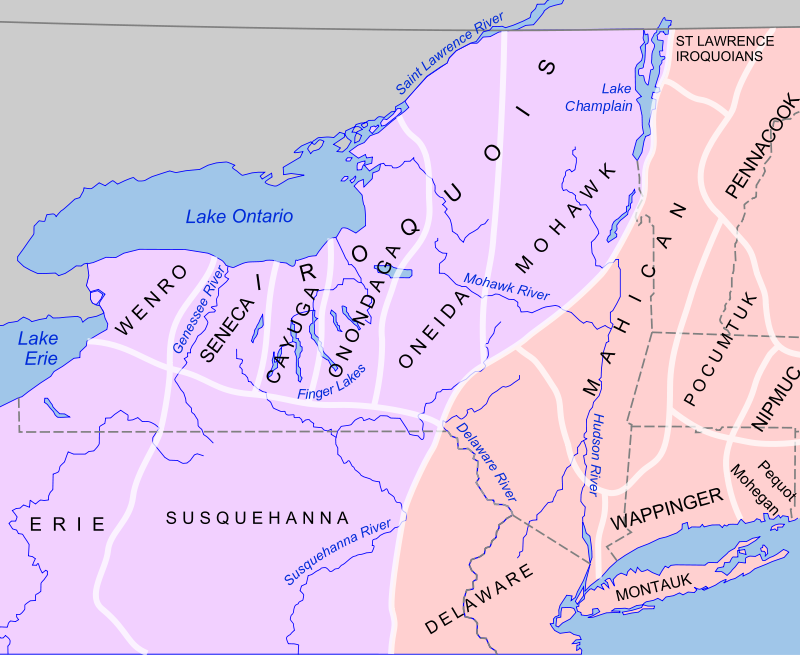

Hämäläinen, notes the importance of Haudenosaunee not for their encounters with Europeans to the east as is typically done but with Indian nations to the west. “The Haudenosaunee launched assaults on neighboring groups, absorbing some but pushing others to the West in what he provocatively calls ‘the first large-scale westward expansion in early American history.’” Hämäläinen, states “Iroquois went to war to make other people Iroquois.”

Hämäläinen,’s previous books on the Comanche and the Lakota included the characterization of those nations as aggressively expansionist power who themselves pushed aside other peoples and often dominated European settlers.

The separate book review in The New York Times on the same book lauds it. The review states “(o)ne of his recurring themes is how limited the Europeans were in their range of action. Essentially, the English, French, and Spanish did nothing without the approval from one or another Native American tribe or confederation.” The Sioux expanded westward with the combination of musket and horse. They became a superpower dominating the Upper Mississippi Valley. The Comanche did the same in the Southwest. Everything changed with the discovery of gold. It brought people, trains, and the rifle which were deadly to the buffalo, the Sioux, and any local people who were in their way.

A precursor appeared in the article “The Shape of Power: Indians, Europeans, and North American Worlds from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century” in Contested Spaces of Early America (2014). In that article, Hämäläien bemoans the atomization of history with tightly focused monographs and the loss of continental vision for curiously one dimensional history. Interestingly, Hämäläien suggests a single master narrative for early American history “is irrevocably in the past.” The implication is that a master narrative for American history folly.

He states that “Indians held sway over much of the continental interior during the so-called colonial era” lasting until the late 19th century. The Apaches and Comanche on the short-grass plains relied on raiding and nomadic mobility to protect them and to expand their territories into regions claimed by Spain. The Comanche, who were not indigenous to the Southwest, relied on overpowering equestrian mobility in a five-decade war with the Apache. The Apache then retreated to into southern Texas and northern Mexico where they were not indigenous either.

The Lakota, too, expanded westward and southwestward. Guns and horses gave them an edge over village farmers and hunter nomads into the plains.

A century before the American Revolution, the Iroquois was the dominant territorial power in the eastern woodlands. Along with the Comanche and Lakota, they carved out vast domains by projecting overwhelming violence. The famed Covenant Chain with the English “bestowed the Iroquois with unparalleled political clout, which they leveraged on other fronts to pacify their borders and reduce their rivals to security buffers. Their war parties ranged from the Ottawa Valley to the Upper Great Lakes and the Carolina Piedmont. The unity of their multi-ethnic tribal confederacy was maintained through councils.

One should distinguish between French maps extending west of the Mississippi and the reality of multiple confederations and nations boxing France in.

Overall, colonial control was limited to relatively small coastal and riverine outposts. The great interior remained closed to the European settlement. Much of North America remained unknown to Europeans in the 1760s. As late as he 1780s more than three quarters of the continent was outside European/American control. A book reviewer of Lakota America A New History of Indigenous Power wrote “as Meriwether Lewis and William Clark discovered, the Missouri River valley was in actuality Lakota, not United States territory” which is not how their expedition is taught (American Historical Review March 2021:6).

The Iroquois, Comanche, and Lakota were all the beneficiaries of geography. They were removed from the colonial rim of European without being isolated from it. They all were adaptive of new technologies and to the changes from European settlement.

The purpose here is not to review the entire scholarship of Hämäläien or even to judge it. Instead it is to note it as an alternative voice to the traditional views of Indians as two-dimensional beings, either as victims or as woke. As Hämäläien portrays them, there is a story to be told in the centuries from Pocahontas to Geronimo over control of the land. Although the level of violence has decreased today, we can see that there are many unresolved issues regarding land and the relationship of Indian nations to the American nation.

AFRICAN AGENCY

Reading these articles about Indian agency in the United States made me think of the issue of African agency expressed in “Africa’s Revolutionary Nineteenth Century and the Idea of the ‘Scramble’” by Richard Reed (AHR 126:4, 2021). The article covers the period mainly from the 1870s through World War I in Africa. The “Scramble” refers to the European carving up the continent into colonial possessions that lasted until the 1950s and later. Indeed, many of the headlines about crises in Africa today derive from the artificial boundaries created by European powers roughly 150 years ago. Interestingly, by chance or design, the word “scramble” was just used in a newspaper article about the current African conference in Washington to describe the actions of Russia, China, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and the United States (“Biden Is Bringing Africa’s Leaders to Washington, Hoping to Make Deals,” NYT 12/12/22 print).

Reed’s goal is not to diminish or deny the “brutal efficiency” by the Europeans. Instead his goal is to recognize that Africans themselves already had initiated a partition and thorough going reformation of Africa long before the Europeans intervened. In other words, the Scramble did not occur in a vacuum.

Reed takes his discipline to task. He claims that historians of empire and imperialism rarely converse with their Africanist colleagues. He states that interest in the Scramble has declined markedly while decolonization has become much more fashionable. He provocatively asks why Ethiopia survived the Scramble as an independent state.

In effect, Reed posits that the 1870s-1880s has become a chronological cutoff point for scholars studying Africa. A rupture occurred then that segregated African history prior to the Scramble. He asserts the need to recognize that “the deleterious effects of the slave trade does not preclude acknowledging that African agency was extraordinarily important in shaping the Atlantic world on both sides of the ocean. “ Furthermore, there were a “multitude of African societies and cultures engaged in the slave trade with vigor, leading to some of the most remarkable, enduring, and globally connected political systems anywhere on the continent, or indeed anywhere at all.”

Reed champions what the Africans were achieving on their own independent of and prior to the Scramble. He writes:

In practical terms, the partition can only be understood as an Afro-European affair: African agency was not simply supportive of but essential to empire-building projects designed in European capitals.

Rather than focus on the traditional idea of European advantage in military technology at the end of the 19th century, Reed suggests “the Scramble was only made possible through a concoction of local alliances and a generous dollop of good fortune.” There was European imperialism and African imperialism. Reed examines the role of different entities within Africa and the growing importance of the Indian Ocean exchange networks.

For Reed, “Africans rather than foreigners were the primary agents of change over a somewhat longer durée than the conventional time frame that the Scramble itself allows.” He thinks “an increasingly presentist interpretation of the continent’s ‘condition’” has led to the African achievements of the dramatic nineteenth century to be overlooked:

The long nineteenth century, a remarkably transformative episode in Africa’s modern history, would in time become lost in transition.

I don’t know what Reed’s standing is within the academic community but he did get his article published in the peer-reviewed journal of the American Historical Association.

By coincidence, I happen to be reading the book Wretched Kush: Ethnic Identities and Boundaries in Egypt’s Nubian Empire by Stuart Tyson Smith. “Wretched” is the identifier the ancient Egyptians routinely used when referring to Nubians. Smith writes about Egyptian imperialism: “This classical model of core dominance and peripheral domination downplays native agency.” What has changed?

AGENCY

Just because bad things happen to a people does not mean they should be defined by their victimhood. I doubt that will happen to Ukrainians. It did not happen to Armenians. It has not happened to Jews who are facing a new round of assaults in the United States.

One of the differences is that Ukrainians, Armenians, and Jews are specific peoples. By contrast, Indians and Africans frequently are thought of continentally, meaning you’ve seen one of them you seen them all. Europeans are thought of as individual peoples. They have their own names. They have their own flags. They have their own World Cup teams. They know about their role in the slave trade. This suggests that potentially, African nations can be thought of as separate entities with their own story to tell.

For Indians, the road is much more difficult. Of course, they have their own names. Of course they have their own histories which includes rivalries amongst themselves. The traditional view that their story begins with the arrival of the European is simply untrue. But to make the switch from lumping all Indians together as “”Indigenous” to they are peoples each with their own name and history will be a challenge. To do so requires recognizing that they had agency and should not be defined by victimhood.