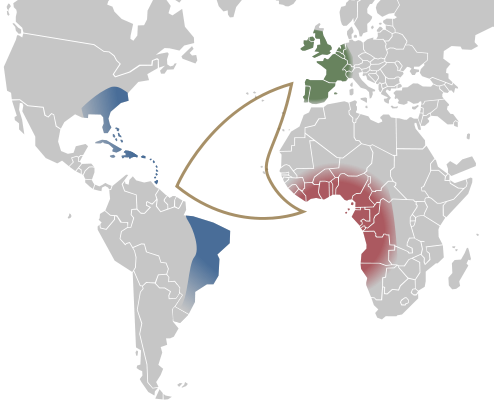

The destruction of Negro communities in the 20th century was not due to slavery. In some ways The New York Times 1619 Project has sucked the oxygen out of the room in its reframing of American history to address current issues. Quite the contrary, the origin of African American should be understood in its historical context which has more to do with racism than slavery.

The destruction of Negro communities was due to a series of racist decisions made in the 20th century. White people made these decisions mainly in the decades from the 1930s to the 1960s. They were in response to a slightly earlier event, the Great Migration, where millions of people migrated from the South to the North. That movement led to the North being faced with questions it had not had to address before, at least not to this magnitude. The response was series of decisions culminating in the 1960s with Negroes burning the very cities they had migrated to, followed by the birth of the African American.

In this blog, I would like to trace the trajectory of Negroes as immigrants to show what might have happened without racism. Then I will turn to what did happened with racism.

GREAT MIGRATION

It is often said that America is an immigrant country. It is a place people migrate to in order to live the American Dream. In the 19th century, waves of German and Irish immigrants followed this trajectory. They often arrived in Castle Garden in lower Manhattan.

Subsequently another wave of immigrants from Europe arrived in the United States also through New York. These Ellis Island immigrants are associated with the Statue of Liberty both of which can be visited. The geographical origin of the European immigrants shifted to southern and eastern Europe. It included most prominently Italians, Jews, and Slavic peoples. It was at this time that the “melting pot” image really developed along with the role of schools in educating the immigrant children in English, civics, and American history.

The Great Migration of Negroes from the South should be understood within this context. By that I mean the path these immigrant Negroes from the South took should be compared to the path the Ellis Island immigrants from Europe took in living the American Dream to determine where they coincided and where they differed.

In some ways, the Great Migration provides an opportunity for the concept of contrafactual that one hears about in historical studies. It refers to “what if?” What if a different decision had been made? What if a different action had been taken? What if you had never been born? Here the question is what if the Negro immigrants to the North had followed the same path as the Ellis Island immigrants who arrived in roughly the same locations at roughly the same time? That will be the subject for the rest of this blog. Since we know that the paths differed and often put the two groups at odds with each other, the next blog will examine the parting of the ways. At the beginning of this path neither Italians nor Jews were considered to be white either. Eventually, they did become white although anti-Semitism continues to this very day.

LIVING THE AMERICAN DREAM

When the Negroes migrated North such as to New York City, they seemed to be on the path to being accepted as Americans and living the American Dream. Earlier blogs touched on this subject.

Negroes and the American Dream: Hidden Figures, Open Dreams (March 11, 2018)

What Should You Call Middle Passage Descendants? (January 16, 2022)

Now, I wish to start with the article “The Privilege of Family History,” by Kendra T. Field, a self-identified descendant of African and Creek ancestors (American Historical Review 127 2022: 600-633). As part of her investigation, she notes in the 1800s that people who knew that their fathers had been born in Africa “often claimed their fathers quite loudly.” In an early version of Roots, Field cites Henry Highland Garnet’s family tracing its origin to a Mandingo chieftain and warrior. Knowledge of that African connection was something to be championed:

“Are there any survivors of the later importations from Africa, or are there any Negroes who can say today ‘My father or my mother was a native African?’” (Southern Workman, Hampton Folklore Society, 1893).

She contrasted these quests with people like Frederick Douglass who was the son of his white owner and similar people who were more reticent about their origin. Field uses that contrast to observe that white people were dismissive of the very idea of a family history anyway culminating in the book The Negro Family by Daniel Patrick Moynihan in 1965 (just before the Negro would be replaced by African American).

Perhaps not as well-known, Field reports on the controversy post-Emancipation of the public shame in admitting that one even had slave ancestors. By the end of the 19th century, Field reports on the necessity to actively collect stories, practices, and folklore from their elders.

“The America Negroes are rising so rapidly … that the time seems not far distant when they shall have cast off their past entirely … If within the next few years care is not taken to collect and preserve all traditions and customs peculiar to the Negroes, there will be little to reward the search of the future historian” (Southern Workman, Hampton Folklore Society, 1893).

Field notes a concern expressed by students, alumni, and teachers that the next generation was growing ignorant of what their ancestors had experienced. As W.E.B. Du Bois proclaimed in speech at Howard University:

“there are facts of Negro history unknown to most of us and destined to remain so unless unearthed and published by historians of our own race.”

Can you imagine the younger generation today asking parents and grandparents born before 1965, what is was like to be a Negro? That’s like asking to be fired as a professor.

But a century ago, Howard University had witnessed a growth in awareness of Negro culminating in a course on the Negro in American history. Soon there were a slew of bulletins, journals, and books about the Negro in American history.

In “America’s Second Sin: How an Overlooked era still shapes our world” by Henry Louis Gates Jr. (Time April 15, 2019), he writes about the post-1895 development of The New Negro. It arose as a counter to the avalanche of racist images proliferating throughout Gilded Age America. Gates refers to them as superheroes fighting the good fight against these supremacist images. That period from 1895 to the Harlem Renaissance witnessed a series of individuals championing the Negro cause through a variety of media in the battle for respectability. It perhaps culminated with the artistic anthology “The New Negro: An Interpretation” by Alain Locke (1925). It was during this time that James Weldon Johnson’s poem “Lift Every Voice and Sing” (1900) became the Negro National Anthem. But as with Negro Wall Street in Tulsa, it is no longer appropriate to use historically correct names when referring to anthem.

Negroes even had their own elites. For example, “Configuring Modernities: New Negro Womanhood in the Nation’s Capital, 1890,” by Treva Blaine Lindsey (2010). The dissertation subsequently was published as book Colored no more: reinventing black womanhood in Washington, D.C. (2017). As the titles suggests, the focus is fifty years in a single city, the nation’s capital.

Another publication drew on the author’s own experiences in Chicago, Negroland: A Memoir, an award-winning book by Margo Jefferson, formerly of The New York Times.

She writes:

Negroland is my name for a small region of Negro America where residents were sheltered by a certain amount of privilege and plenty. Children in Negroland were warned that few Negroes enjoyed privilege or plenty and that most whites would be glad to see them returned to indulgence, deference and subservience. Children there were taught that most other Negroes ought to be emulating us when too many of them (out of envy or ignorance) went on behaving in ways that encouraged racial prejudice.

Obviously, one cannot do full justice in a blog to the achievements during the Negro Century. Nor can one review all the differences in opinion held by historians about this era. The more important point is to recognize the American history did not simply jump from slavery and Jim Crow to the Civil Rights era and African America as if there was nothing in-between. There were great successes for Negroes during this period which placed them on the path to living the American Dream except for racism.

The name change in the 1920s is worthy of note. The New Negro built on the legacy, heritage, and history of the people as Negroes. By contrast, the term African American severed people from their own past something the Italians, Jews, and Slavs did not do just as it is unlikely Ukrainians will do. Now there are two gaps in the history of the Middle Passage people – their roots in Africa and their lives between slavery and Civil Rights. It’s as if their story begins in 1619 and resumes with Jim Crow.

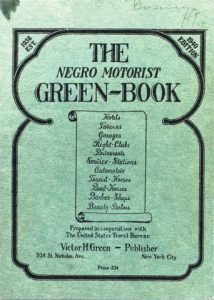

DOCUMENTING ALMOST LIVING THE DREAM

In the time between the Great Migration and the Civil Rights era, Negroes made significant progress towards living the American without actually matching the success of white people. The following information comes from a full page article in the Sunday News of the Week Review in The New York Times on December 6, 2020. It is by Shaylyn Romney Garrett and Robert Putnam, authors of The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again. They also can be viewed online on multiple websites talking about the book.

Their contention is:

In terms of material well-being, Black Americans were moving toward parity with white America well before the victories of the civil rights era. What’s more, after the passage of civil rights legislation, those trends towards racial parity slowed, stopped and even reversed.

They identify multiple measures reflecting this development. They include:

Life expectancy

High School graduation

K-12 school integration

Income

Voter registration.

They attribute a lot of the improvement to the Great Migration itself. Millions of people left the South, home of the Confederates and Jim Crow, for cities in the North. One may add that not only was it a geographical migration but also one from a rural agricultural-based economy and life to a urban and factory based one. As they write:

It was Black Americans’ undaunted faith in the promise of the American “we,” and their willingness to claim their place in it against all odds, that won them progress between the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s and the end of the civil rights movement in the 1970s.

Why this progress plateaued or reverse just when Negroes became African Americans is not the subject of this blog. Instead it is to chart the grounds for optimism that migrant Negroes could match the success of immigrant Italians and Jews in living the American Dream.

AMERICA’S TEAM

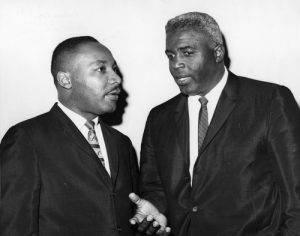

By now, most Americans, at least of a certain age, are familiar with the story of Jackie Robinson leaving the Negro League to become the first Negro to play in the Major Leagues.

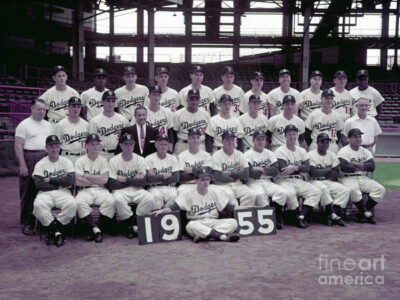

Prior to that, white and Negro baseball players played in parallel leagues, sometimes in the same ball parks but not, of course at the same time. Sometimes barnstorming Major League players, at a time when one could scarcely make a living playing baseball, would play teams from the various Negro Leagues. The crossover of Jackie Robinson quickly led to the demise of those leagues. On the other hand, what greater symbol could there be of Negro assimilation into America than playing for a Major League team? Soon, the cry of “Wait till next year” ended as 1955 became next year against the hated New York Yankees.

But the story does not end there. Brooklyn was an immigrant borough, a borough of ethnics. That carried over into the baseball team that represented them. Consider again the Italian and Jewish immigrants who arrived around the same time as the Great Migration. Already baseball had had its Irish players and managers like John McGraw. Then Germans Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig were added to the baseball mix. Jewish Hank Greenberg of Detroit and, most famously, Joe DiMaggio of the Yankees extended the ethnic range. But it was the Brooklyn Dodgers with Jackie Robinson, Carl Furillo, and then Sandy Koufax who touched the most bases. So back then before the Dodgers abandoned Brooklyn, the Dodgers were America’s team.

So to conclude this optimistic blog on the trajectory of Negroes in the Great Migration, the Brooklyn Dodgers of the 1950s best symbolize the path taken to living the American Dream. The team shows what was possible. Unfortunately for every Branch Rickey who made the decision to include Negroes in the American Dream there were many other white people who made the decision to exclude them.