Judges 19:26 And as morning appeared, the woman came and fell down at the door of the man’s house where her master was, till it was light. 27 And her master rose up in the morning, and when he opened the doors of the house and went out to go on his way, behold, there was his concubine lying at the door of the house, with her hands on the threshold. 28 He said to her, “Get up, let us be going.” But there was no answer… 29 And when he entered his house, he took a knife, and laying hold of his concubine he divided her, limb by limb, into twelve pieces, and sent her throughout all the territory of Israel. 30 And all who saw it said, “Such a thing has never happened or been seen from the day that the people of Israel came up out of the land of Egypt until this day; consider it, take counsel, and speak.”

The story of the rape and dismembered concubine in Judges 19 has been deemed a text of terror.1 Indeed the brutal and horrific treatment of this woman is a story likely skipped over in Sunday School even as it is standard fare in many slasher movies. What is frequently overlooked is that as with the Hollywood movies, no person was hurt in the creation of this story. It was the response to the story that is the key to understanding it.

The story was supposed to be a text of terror. That was the intent of the author. Janet Leigh did not die in Psycho but the audience was supposed to be and was terrorized. Similarly her daughter Jamie Lee Curtis did not die in either versions of Halloween but the audiences were terrorized. So too in ancient times. While the biblical story was not written to be a box office smash, it was written to provoke a reaction by its audience. In some sense, it is related to the murder and dismemberment of Jamal Khashoggi at the instigation of the Saudi Arabian Crown Prince. There is a political dimension to the story in ancient Israel just as there is to the actions today.

The approach taken to understanding the story is critical. The story is a political one. It is not history. It is not theology. It is not religion. It is politics. Mario Liverani addresses the close connection between the writing of history and the validation of political order and political action in the ancient Near East by targeting Judges 19-21 as a possibly pro-Davidic, anti-Benjaminite story from the time of Saul.2 Yairah Amit declares:

Literature has always been susceptible to involvement in political struggle, so the political mobilization of biblical literature should occasion no surprise….I have chosen to discuss…the anti-Saul polemic hidden in chs. 19-21 in the book of Judges.3

…the confrontation between the house of Saul, whose origin is in Gibeah, and the house of David, whose origin is in Bethlehem Judah, is in fact the core of the story.4

Marc Brettler echoes Amit’s statement in seeing the alphabet prose narrative story as an anti-Saul polemic in the use of literature as politics. He wonders why what is seemingly so obvious is rejected by scholars. How can a story which mentions the homes of Samuel, Saul, and David not be a political polemic?5 The story is “a world of unrelenting terror” because that is the message the author wished to deliver in his polemic. But the story is a text of terror mainly for the supporters of Saul because it is a call to arms against them.

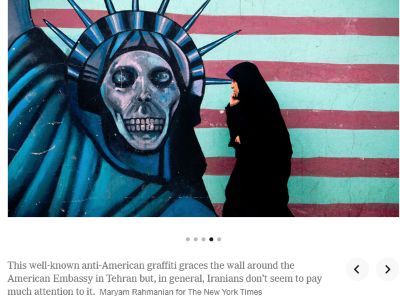

Let’s look at the individual characters in the story and who they represent. First there is the anonymous female just as there was in the preceding story of Jephthah’s Daughter, another text of terror. For this author, the anonymous female does not represent a specific individual in history. Like Lady Liberty, she is a symbolic figure representing We the People or in this case the Israelite people. Her fate is the fate of the Israelite people unless something happens to prevent it.

The figure of the anonymous female automatically raises the question of who is responsible for the safety of the people. As we have just been reminded through some home grown terrorist actions in the United States, the president is the political leader responsible for the safety of the people. In ancient Israel, one might expect the figure to be the king or Saul in these polemical texts of terror. That was true in the Jephthah story. In that story, he fails in this duty despite his military success and the people pay the price. He fails because he has crossed the line: as a warrior he does not have the right to initiate military action. Under the Israelite system of checks and balances that power is reserved to Yahweh acting directly or through his priestly representative.

In the second story, the call to arms is initiated by a Levite priest. He has the authority and now the obligation to do so. In these stories one may observe the ancient equivalent of the American Federalist Papers in the political battle with the Anti-Federalists over the ratification of the Constitution. Still to this very day, the political battle continues over the power of the President versus We the People through the House of Representatives to initiate war. Ancient Israel had a similar debate when kingship arose but expressed points of view through the story form rather than the essay or op-ed.

The stakes had ratcheted up since the Jephthah story. In that story, one individual was held accountable. Now it would be all then men of the city just as it would be in story in Gen. 19 with Sodom replacing Gibeah. Whereas in the story of Jephthah, his own family had disavowed him, in the sequel, all the men bear the responsibility for the crime which occurred. Now it was incumbent on the Levite to right the wrong which had occurred by the Benjamin violation of the Israelite people. To do so, he exercised his authority to call Israel to battle just as Deborah had done. However, it is one thing to call for the tribes to assemble for war, in the end there still needs to be a leader. Who would be the Barak?

The author is not subtle in who he had in mind. He did not need to designate the city of the concubine. He did not need to make that city Bethlehem. But just as Gibeah meant Saul so Bethlehem meant David. The author of this story was reaching out to David to be the leader to restore the order Saul and his Benjaminites had disturbed. David now had a responsibility to do so. Why did the author choose David? Why did he place Israel’s future in David’s hands? Why did he think David would accept this calling from the Levite?

Forget about hindsight. Forgot about people looking back at the establishment of the Davidic dynasty from Persian times. At the time when David emerged in history, no one knew that there would be a Davidic dynasty. This story is a call to action in the hope that David would accept that call. There was no certainty that he would. There was no certainty that if he did accept the call that he would succeed. To some extent, the story functions as a “Hail Mary” by the author if I may mix my metaphors. Then again, he was desperate.

What does that Levite call to David tell us about the Israel in the time before David became king?

First, it tells us that David was an Israelite. David’s ties to Bethlehem do not mean he was born a Judahite. Bethlehem and Ephratah are different names for the same location (Gen. 35:19 and 48:7). Mark Leuchter suggests that אפרתי in I Sam. 1:1 usually translated as “Ephraim” is better translated as “Ephrati” meaning a man of Ephratah. The pilgrimage of Elkanah and Hannah of Ephratah to Shiloh leading to the birth of Samuel therefore indicates a strong connection between the religious circles of Ephratah-Bethlehem and Shiloh.6 Sara Japhet suggests that David, the son of an Ephrathite of Bethlehem of the tribe of Judah (see I Sam. 17:12), belonged to an Ephraimite clan that had migrated south. There it came in contact with Calebites such as Nabal and his wife Abigail whom David later married (I Sam. 25) when he was creating the kingdom of Judah.7

These suggestions help tie together various biblical strands. Nadav Na’aman concurs with this identification. He furthermore suggests members of this Ephraimite clan may have migrated to Gilead across the Jordan River as well. He raises the issue of the connection between the ark and Ephratah (Ps. 132:6) and David’s connection to the priests of Shiloh and their most sacred object. He focuses on Rachel, the eponymous ancestress of the tribe of Ephraim and the clan of Ephrathites. She dies from hard labor when giving birth to Benjamin and is buried by what becomes David’s birthplace in what is known as Rachel’s tomb. Na’aman claims the memory of her death dates to the early Iron Age.8 Albright earlier had suggested that a colony of Ephrathites had established a settlement in the Bethlehem district and had subsequently built Rachel=s Tomb.9 Rachel=s prominent appearance in the third cycle of Genesis stories may be traced back to her importance to David’s Ephrathite clan in the Bethlehem district which had migrated from Ephraim where the Shiloh priesthood was based.

Second, David was an Israelite of some prominence. Whether he had made a name for himself though military exploits against the Amalekites, the Philistines, or both is not the issue here. I accept that he had acquired sufficient stature to warrant marriage to a daughter of the king. What is important is that he was not some unknown person who appeared out of nowhere. Quite the contrary, he already was a successful Israelite warrior with religious ties to Shiloh. The author of this text of terror felt quite comfortable reaching out to him in this time of need.

Third, the author of the story had reason to believe that David felt shortchanged by Saul in some way. Or if not by Saul himself, then certainly by the Benjaminites after Saul’s death who supported Ishbaal as the successor rather than the militarily superior David. In the real world, Saul undoubtedly expected Jonathan to be his successor as did David and there was no provision for both father and son dying in the same battle. Why support the weak surviving son and not the vibrant son in-law…other than the fact that he was Benjaminite and blood? The presence of David was less a threat to Saul as king than to Saul as dynasty founder. A successful story of David’s rise to power would need to show that David never had been such a threat.

We may never know that precise details of the political machinations which occurred at that time. What we do have are the texts of terror, Abiathar, the father of the alphabet prose narrative, wrote during the early part of his career when he first reached out to David.

References

1.The phrase comes from Phyllis Trible, Texts of Terror: Literary‑Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984).

2. Mario Liverani, Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004), 160-192.

3. Yairah Amit, “Literature in the Service of Politics: Studies in Judges 19-21,” in Henning Graf Reventlow, Yair Hoffman, and Benjamin Uffenheimer, ed., Politics and Theopolitics in the Bible and Postbiblical Literature (JSOT Sup Series 171; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994), 28-40, here 28.

4. Yairah Amit, “The Use of Analogy in the Study of the Book of Judges,” in Matthias Augustin and Klaus Dietrich Schunck, ed., Wünschet Jerusalem Frieden: Collected Communications to the XIIth Congress of the International Organization for the Study of the Old Testament, Jerusalem 1986 (Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang, 1988), 387-394, here 391.

5. Marc Z. Brettler, “The Book of Judges: Literature as Politics,” Journal of Biblical Literature 108 1989: 395–418, here 402.

6. Mark Leuchter, “Jeroboam the Ephraite,” Journal of Biblical Liteature 125 2006:51-72, here 60-61.

7. Sara Japhet, “Was David a Judahite or an Ephraimite? Light from the Genealogies,” in Iain Provan and Mark Boda, ed., Let us Go up to Zion: Essays in Honour of H. G. M. Williamson on the Occasion of his Sixty-Fifth Birthday (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 297-306.

8. Nadav Na’aman, “The Settlement of the Ephraites in Bethlehem and the Location of Rachel’s Tomb,” Revue Biblique 121 2014:516-539.

9. William F. Albright, “Appendix II Ramah of Samuel,” AASOR 4 1922-1923:112-123, here 118-119n.6.