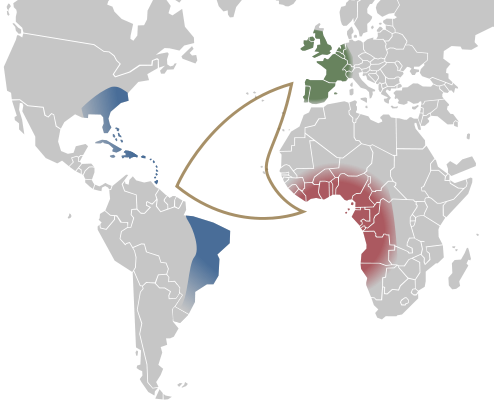

New York has experienced demographic change. There is a difference between between being the descendants of people who left Ghana centuries ago against their will to become slaves in New York and elsewhere in what became the middle passage and those who left Ghana recently by jet plane of their own free will to live the American Dream.

The catalyst for my personal odyssey about this topic occurred in January, 2016, when Whitesboro, NY, briefly held national attention. The reason for the notoriety was the municipal seal. It appeared to show an interaction between Hugh White, the founder of the community, and an Oneida chief that was derogatory towards the latter. A cable comedy-news show sent someone to Whitesboro to gather material for the show. In the course of a conversation between that person and a local resident the issue of race came up. The local resident replied using various terms including “Negro” to identify the race of the media person. At that point the person looked taken aback as if another word had been used. Truth be told, all the reactions of the media personality were over-the-top physical exaggerations who clearly was playing to the camera so it was difficult to determine if the response was genuine or not.

Nonetheless, the reaction whether real or faux suggests that there is a story to be told about the use of the word “Negro” for middle-passage blacks that is part of American history. When I was growing up in a naturally occurring [meaning not court-ordered] integrated [I did not know that word then] elementary school there were students who looked different than me called Negroes. To the best of my recollection there was no discrimination [another word I did not know] against them in the classroom or on the playground, the world I knew as an 8 year-old. The visible segregation [another word I didn’t know] was the unofficial one on the playground where the boys played kickball and the girls jumped rope or played hop scotch. If I had been asked my identification I probably would have said Jewish meaning not Italian or Irish and not have responded “white.” So when I was growing up Negro simply was the name of one group of people in the community.

The incident in Whitesboro caused me to pursue the history of this terminology further. Certainly I am aware that the term is not the one used today to refer to black people but in and of itself that change in terminology did not necessarily make the word a pejorative. It wasn’t one when I was growing up.

The term means “black” and refers to the black-skinned people in Africa the Portuguese and/or Spanish encountered during their explorations to Africa in the 16th century. It was descriptive in nature of an obvious physical characteristic that clearly differentiated the two peoples. In that sense it was not a derogatory term in its origin. That stark difference in colors between the white and black-skinned peoples very much was part of the historical context in which slavery began in this country.

These Negroes in America were a factor in the American Revolution on both sides. The British successfully recruited some of them to join their side against the Americans. Consider this excerpt from a recent July 4th article The Secret Black History of the Revolution

John Murray, Earl of Dunmore by Charles Harris.

Courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, VA.

From 1772 on, Royal Governor Dunmore of Virginia had threatened rebellious Patriots. “It is my fixed purpose,” he said, “to arm my own Negroes and accept all others whom I shall declare free… and I shall not hesitate at reducing [Patriots’] houses to ashes and spreading destruction wherever I can reach.” By the time he issued his Proclamation on Nov. 7, 1775, thousands of blacks had flocked to the British side to join his Royal Ethiopian Regiment. Because of Dunmore and the High Court’s 1772 Somersett decision that bondage was outlawed on English soil, the Southern states seceded from Britain to preserve slavery. In his 1775 “Taxation not Tyranny,” Samuel Johnson, the great English essayist, rightly quipped: “How come we hear the greatest yelps for liberty from the drivers of Negroes?” [Bold added]

While the white authors today employ the term “black,” the British then used the term “negroes.” It is reasonable to conclude that the British did not attempt to recruit people to their cause by referring to them in what they thought was a derogatory manner. It was a term both peoples used and the usage is consistent with the way I had been brought up.

By coincidence, just recently a slavery story made the news right where I live. The reason was the discovery of a note in the archives of the Rye Historical Society for the sale of “my Negro girl named Pegg” by prominent Greenwich property owner, Daniel Lyon, on July 7, 1790 to another major Greenwich property owner, Nathaniel Merritt Jr., whose family gave its name to the Merritt Parkway. [On a personal note I live on land that once belonged to Lyon and indeed the community is named after him as is the nearby village park.] She was freed in 1800 and has descendants who live in Westchester County. Indeed the genealogical research by one descendant investigating the family name “Merritt” that led to the discovery.

Daniel Lyon Jr.’s bill of sale — dated July 7, 1790 — of “my Negro girl named Pegg”

to Nathaniel Merritt Jr. of Greenwich, Conn. (Photo: Rye Historical Society)

The discovery serves as a reminder that black New Yorkers can trace or have ancestors from prior to the Great Migration from the South, prior to Ellis Island immigration, and prior to Castle Clinton (Irish) immigration. Just as New York ignores July 4, 1827, in its history so it ignores or minimizes the history of the blacks once they became free in the antebellum period. There is more to black history in New York than the discovery of burial grounds from colonial times or the underground railroad. The recently refurbished, then vandalized, and then cleaned-up African Cemetery owned by the Town of Rye since 1860 where I have been numerous times is one example of the effort to remember that history of free blacks from that time period.

(Left) Dennis Richmond Jr., 21, of Yonkers, and his uncle,

John Sherman Merritt, 75, of the Bronx, in the Rye Historical Society’s Knapp House.

The discovery also provides a teaching and civic opportunity to use local history to address state and national issues.

This post on the use of “Negro” is not intended to be comprehensive but there are additional illustrations which deserve to be revealed before concluding.

Professor Booker T.Washington, being politely interrogated … as to whether negroes ought to be called ‘negroes’ or ‘members of the colored race’ has replied that it has long been his own practice to write and speak of members of his race as negroes, and when using the term ‘negro’ as a race designation to employ the capital ‘N’ [“Harper’s Weekly,” June 2, 1906]

Calvin Coolidge in 1923 and again in 1925 urged the creation of a “Negro Industrial Commission” to promote a better policy of mutual understanding.” In 1929 in the waning months of his presidency, he signed legislation for a memorial celebrating “the Negro’s contribution to the achievements of America.”

JamesWeldon Johnson, the first black to head the NAACP, described a meeting he had with Coolidge brokered by Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.

I was expecting that he would make, at least, an inquiry or two about the state of mind and condition of the twelve million Negro citizens of the United States. I judged that curiosity, if not interest, would make for that much conversation. The pause was painful (for me at least) and I led off with some informational remarks; but it was clear that Mr. Coolidge knew absolutely nothing about colored people. I gathered that the only living Negro he had heard anything about was Major Moton (Booker T. Washington’s successor at Tuskegee). [Bold added]

Negro History Week was celebrated for the first time in 1926 during the second week in February. This month was chosen because Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln celebrated their birthdays during this month. Later it would be renamed and become a monthly dedication as it is now.

These examples attest the continued use of the term by both blacks and whites without any negative connotation into the opening decades of the 20th century. They are consistent with the usage from when I was growing up.

This era also was the time of the Negro Baseball League. For several decades it thrived as the major leagues for Negro baseball players. Its teams would barnstorm with players from the white Major League baseball teams. Some of those players have been installed at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. There also is a separate Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

Courtesy of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and Wikipedia

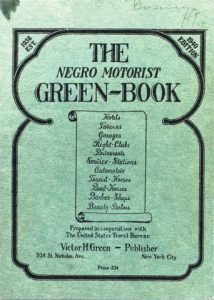

Traveling was a problem so in 1937, The Negro Motorist Green-Book was created to aid people in finding places to eat and sleep. It lasted from 1937 to 1967. The Smithsonian Magazine recently featured it with an article reporting that it is the subject of a documentary-in-progress by Ric Burns.

During World War II, the United States recruited middle-passage blacks to join the war effort by joining the military. This continued a pattern of their fighting on behalf of the United States in every war the country fought. One such recruiting effort was the Navy film in 1942, The Negro Sailor (available on YouTube). Again, it seems unlikely as with the British during the American Revolution that recruiting efforts would have been aided through the use of a derogatory term to refer to the people being targeted. It continued to be a term both races uses without a negative meaning into the 1940s.

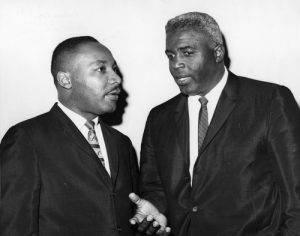

All the pieces came together after the war when Jackie Robinson, a war and Negro League veteran, became the first Negro to play for the Major Leagues and in 1962 was elected to the Hall of Fame.

Original caption: 9/19/1962-New York, NY: The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (L) and baseball Hall-of-Famer Jackie Robinson chat together before a press conference in New York, September 19th. Dr. King, who arrived to open a drive for funds and a northern “non-violent army” of clergymen and followers to battle segregation, said the “real showdown” in the segregation fight was the struggle to get negro James Meredith into the University of Mississippi.(Original caption). September 19, 1962 New York, New York, USA [bold added]

Following Robinson and even more famous Negro garnered national attention. Martin Luther King was a frequent user of the term “Negro.” He dreamed of what Negroes in the United States should have the opportunity to achieve. His use of the term may present challenges in teaching and in exhibits particularly with young students who are not familiar with the historical context and then suddenly hear a word it in a speech that they are not used to hearing.

The current issue of Time includes an excerpt from James Baldwin written in 1964 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. It is from a letter of a father to his son today:

…in every generation, ever since Negroes have been here, every Negro mother and father has had to face that child and try to create in that child some way of surviving this particular world… [Bold added]

Here again is an example about the continuing presence of terms from the past. We are confronted here not with changing a name from New Amsterdam to New York reflecting a political change. Rather the values and associations produced by the same word have changed over time. What the word meant to the black man who was alive in 1964 and what the word means to his son today to whom his letter was addressed are not the same. Readers of the magazine separated by time in when they grew up therefore may respond differently to the article depending on how they react to the same word.

In 1968, a biracial person wrote a letter to the biracial (actually bi-species) Mr. Spock of the Starship Enterprise. She wrote that her mother was Negro and her father was white and appealed to the half-Vulcan, half-human Spock because of the suffering he had endured. The human Leonard Nimoy, son of Jewish immigrants who had settled in Boston, wrote her a long letter in response. Little did this teen girl know that when she grew up, this self-reference itself would be an abomination to be cleansed from the maps and vocabulary of civilized people.

This survey ends in the mid-1960s. At that time Negro began to be unacceptable and was replaced by a new term to refer to the same people. My experience with name change may be different from that of blacks. As mentioned, I am Jewish. Part of my heritage are the memories of the ghettos, pogroms, and holocausts which have been perpetrated against Jews. If we were to change our name because of these actions, then I would consider that an act of surrender to anti-Semites. I oppose the bad and evil things which were done and to want them not to be repeated. I do not hold my name in contempt as a legacy of those bad and evil things. Being called a Jew is not a pejorative despite the harmful actions targeted against us. I bring my own traditions and experiences to my understanding of the name “Negro” both as a Jew and from when growing up. I remember how hard Kunta Kinte fought to keep his name.

Recently our government became involved in the issue. In May our president signed a bill which removed the word “Negro” from federal law and requires the use of African American instead. The rationale is that the older term causes people to cringe today as the performer in Whitesboro did. The law amending Section 211(f)(1) of the Department of Energy Organization Act (42 U.S.C. 7141(f)(1)) wasn’t in place then in January at the time of the Whitesboro interview. It only applies to laws not speech. Similarly there is an effort underway in Connecticut to change the name of the rock formation Negro Heads in Branford. According to State Senator Ted Kennedy, Jr., the name is anachronistic and offensive. In other words, a term used for centuries by both blacks and whites to refer to the same people now was officially designated as being offensive. Ironically the one individual American to have a federal holiday in his honor repeatedly used a word which the federal government now declares to be unacceptable as a matter of law.

As it tuns out, after this virtuous “whitewashing” of the word Negro, the banished term has refused to disappear. Despite the politically-correct effort to remove this stain from the American social fabric, it is not easily deleted. For example, the New York Comedy Festival in November, 2016, includes the show “The New Negroes.” The title derives from the 1920s Harlem Renaissance anthology book The New Negro by Alain Locke. In an interview on the show, rapper Open Mike Eagle said:

“[The] provocative nature [of the title] challenges the notions of what is conjured when people think of that name. I felt like I was allowing the politics around the N-word to affect something that was important to us culturally. I want us to protect that [the word Negro] and not let it go just because people have taken it and associated it with these terrible behaviors and attitudes.” (“Illuminating What It Means to be Black in America, via Comedy,” NYT 11/2/16)

Another change accelerating after the 1960s when Negro fell out of favor, was the composition of black people in the United States. Immigration laws changed. Since then especially more recently, the demographics of blacks in New York has changed in the city as well as in refuge cities upstate. Politicians campaigning in the boroughs of New York City know that all the black people don’t have a shared nearly 400-year history of being in the United States or the colonies. These newcomers aren’t simply from the South as the earlier migration last century but from other countries. Their presence in the city generates the question of what they should be called.

In a recent op-ed piece, Yaa Gyasi wrote “I’m Ghanian-American. Am I Black?” The author raises an important issue. Although Ghana served as a depot from which human cargo was transported to America as slaves in what is called the middle passage, Ghanaian-Americans today, like those from Nigeria, Senegal, Angola and elsewhere, are likely to have arrived by jet. The Mayflower, middle passage, Ellis Island, and JFK Airport arrivals present different models for how people came to this country. Again there is a civic and education opportunity to examine the different forms of arrival and to discuss what it means in a country defined as “We the People.” Times have changed, new circumstances have arisen, new contexts have developed, so it is reasonable to wonder if vocabulary changes are needed as well as indicated by the title of the Ghanian-American’s op-ed piece.

For example, typically Irish and Italian Americans are identified by their country of ancestry just as this Ghanaian seeks to be. In general, immigrants do identify themselves by their country of origin or ancestry. Two recent presidential candidates were Cuban-Americans and not Latin Americans. That option obviously is not available with middle-passage blacks. The new science of DNA testing is being used to identify the geographical range of origin for blacks and has been the subject of several TV shows with black celebrities. In a world of global migration sometimes through multiple countries and where people of multiple colors live on the same continent, the old binary black-white classification system in America may be too limiting.

So why was the name which middle-passage blacks brought to America were called by themselves and by others changed in the 1960s after centuries of use? What terminology should be used to differentiate those people who have been in America for centuries and who fought in the American Revolution from those who recently arrived as immigrants of their own free will?

These questions touch on the larger questions of great importance to our future beyond the immediate scope of this post. What do the concepts of “We the People” and e pluribus unum mean when people of the same and different colors have such different experiences as Americans? When Lincoln said “Four-score and seven-years ago, our fathers,” he knew that many people in the audience and in the Union did not have ancestors in America 77 years earlier when we declared our independence. He certainly knew the importance of names. As a result of Lincoln the United States changed from being a plural term (they are a country) to a singular one (it is a country). For Lincoln, those who stood for America in the present were one with those who stood for America at its founding. Now we are twelve-score and zero years from that moment. Who will be our Lincoln today?

The Journey continues