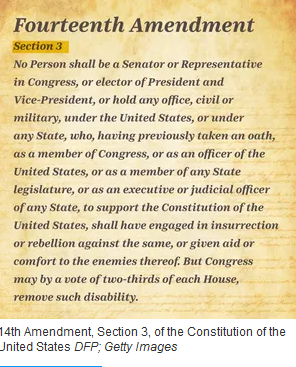

This blog addresses the third of the three historian briefs submitted to the Supreme Court in support of the decision by the Colorado Supreme Court to disqualify Donald Trump from running for President of the United States under Amendment 14 Section 3.

JILL LEPORE

Before turning to the brief itself, Jill Lepore, one of the historians, wrote an article “What Happened When the U.S. Failed to Prosecute an Insurrectionist Ex-President (New Yorker, December 4, 2023, online). The subject is Jefferson Davis, the ex-President of the Confederate States of America. Almost the entire article is about the failed effort to try Davis either for treason or under Section 3.

Amidst that recapitulation she raises some questions about today.

Can Donald Trump get a fair trial? Is trying Trump the best thing for the nation? Is the possibility of an acquittal worth the risk?… But the failure to try him is an affront not only to democracy but to decency…

Several times she expresses her awareness that no what verdict is rendered about half the country would not accept it. In these small digressions scattered throughout the article she has touched upon the core truth of the effort to disqualify Trump – the country is too divided for the issue to be resolved legally. Ultimately one should note it is a political problem and fortunately, not yet, a military one.

AMICI CURIAE: LEPORE, BLIGHT, FAUST, WITT

The reason for the filing of the brief is due to its gravity and “the necessity of grounding any decision in a proper historical understanding of Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment” (Page 2). To do so requires “establishing the original intent, meaning, and public under understanding of the Disqualification Clause” (Page 2). Here they are using one of the jargon terms favored by the Trump judges on the Supreme Court.

They state the concern in the aftermath of the Civil War was:

That office-holders who had violated their oaths to the Constitution would reassume positions of authority, destabilize state and federal governments, and suppress freedom of speech. The Republican framers of the Amendment believed that anything short of the disqualification of insurrectionists risked surrendering the government to anti-Constitutionalists rebels (Page 2).

Considering the fact that an election-denier is the Speaker of House, this concern should be applied to a wide swath of people and not just to Donald Trump.

According to these historians, the framers “hoped not only to prevent a resurgence of secessionism but also to protect future generations against insurrectionism” (Page 3). Given the actions of Texas on its border with support of 25 governors and the state of Utah ratifying a nullification act, it would seem that banishing one and only one individual from the ballot seems like avoiding the issue. The intention was not that the amendment only would apply to Jefferson Davis and no one else. It was intended to apply to all Confederates including those who had run for the House and Senate.

Much of the remainder of the brief recounts the history leading up to the ratification leading up to the disqualification section. Sometimes they show that the circumstances involving the MAGAs and the Confederates are quite different without saying so. For example:

Northerners undertook to purge Confederate sympathizers from positions of authority both inside and outside of government and, in mass meetings called upon Congress to do the same (Page 6).

No such purge has occurred today. In fact, the exact opposite has occurred. Real Republicans who know the election was not stolen are the ones who have been purged from Congress or chosen to retire. The historians refer to Frederick Douglass who charged that many Confederate sympathizers remained within the federal government (Pages 6-7). In fact that is the exact situation now where the insurrectionists remain in Congress today and do so quite openly.

With this background in mind, the historians move on to the drafting and ratification of Section Three (Pages 15-26).

Lo and behold! Congress discovered continuing hostility in the southern states (Page 15). This realization strengthened the determination of the winning side to prevent representatives from the losing side being elected to office.

Sounds like MAGA.

In testimony before Congress J.W. Alvord of the Freedman’s Bureau was asked about the rebel feeling towards the government of the United States. His reply was:

There is evidently no regret for the rebellion, but rather a defence of it (Page 16).

Sounds like MAGA.

He was then asked about what the Confederates sought to achieve by their readmittance to Congress. He replied:

They seem to suppose that by re-admission they can get political power and obtain again the supremacy which they once had, with the exception of slavery.

Sounds like MAGA.

A tax examiner said:

No. I think they have a stronger aversion and dislike of the Union than when they seceded (Page 17).

Sounds like MAGA.

The initial ratification attempt failed. The Southern states as one might expect, opposed it. This action:

…reflected the emerging ideology of the Lost Cause, a tenet of which was the argument by ex-Confederates that they never had engaged in “rebellion,” should never be considered “rebels,” and had merely exercised legitimate rights of “sovereignty” with secession and war [it was legitimate political discourse] (Page 25).

Sounds like MAGA.

Matters came to a head in March 1867 when over a Presidential veto, Congress passed the Military Reconstruction Act. That Act stipulated that no state could be re-admitted without first ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment (Pages 25-26). In other words, it was the military power of the victorious Union which made the Disqualification section the law of the land.

In the final section, the historians turn to the persistence of Section Three. The story returns to Jefferson Davis and the inability to try him for treason. They call Davis a “cautionary tale” on the danger facing the nation if the leader of an insurrection could run for President (Page 30). They note by 1872, the number of petitioners requesting amnesty under Section 3 at between 15,000 to 16,000 people (Page 31). They also note that ex-Confederates would be elected governor and to other offices across the South (Page 32).

CONCLUSION

These historians have made a very strong case for the applicability of the 14th Amendment Section 3 … only not the one they think they made. They constantly refer to Jefferson Davis and his potential run for President. The implication is that the amendment was designed with someone like Donald Trump in mind.

But they acknowledge the widespread antipathy towards the Union by the defeated Confederates.

They acknowledge that it required the Military Reconstruction Act to implement disqualification in practice.

They acknowledge that thousands of people sought re-instatement from Congress.

As much as they focus on one individual, Jefferson Davis, they actually are making a case why all Confederates were disqualified. The current parallel is that all the MAGA who are election-deniers should be disqualified as well. But they can’t call for such a blanket consolidation because they know the war is not yet over and MAGAs could yet triumph. It is hard to see how this brief would persuade the Supreme Court to remove Donald trump from the ballot.