We are a storytelling species. In this post I would like to share one example of the potential for storytelling in our communities using primary source documents. In subsequent posts, I intended to share other examples from different formats and venues showing how different history organizations and people are reaching out to audiences in different ways from the standard house tour.

In my post on the recent Stockbridge Indian conference held in Stockbridge, MA, I wrote:

In this year’s conference, one of the most moving and poignant sessions was the “Words of Our Ancestors. “ There was a series of ten readings from what would be deemed primary source documents in educational parlance. These readings stretched from 1735 to 1864. They consisted of letters, petitions, deeds, speeches, and personal memories. What made the readings extraordinary is that the readers were the descendants of the writers. It wasn’t simply me reciting the Gettysburg Address as a classroom exercise, but people with a direct biological tie to the creators of the words. If one were to combine these words into a unit, one would tell the story of a people and a community for over one hundred years. It would work even with students who were not descendants such as the residents of Stockbridge today. These words are part of the local history, part of the history of the place.

In response to that post, I received a comment about those documents:

I am a historian in Black Rock, CT working on various projects and wonder if I could learn more about the primary source documents which you mentioned in the lovely email posting. One of the aspects of projects which I work on involve digitizing and transcribing historic documents which preserve them and make them understandable to both students and scholars.

Thanks so much.

Robert Foley

Black Rock history

I thereupon contacted the Stockbridge Indians and received this reply:

“Words of our Ancestors” presentation is now uploaded to Stockbridge Munsee Community’s website, you can find it here: http://mohican.com/mt-content/uploads/2018/06/words-of-our-ancestors.pdf

Bonney Hartley

Tribal Historic Preservation Officer

Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Tribal Historic Preservation

Extension office

65 1st Street

Troy, NY 12180

(518) 244-3164

Bonney.Hartley@mohican-nsn.gov

www.mohican-nsn.gov

I then did download the PDF.

My suggestion at the conference was that the Stockbridge Indians work with the Stockbridge teachers to create lesson plans based on these documents. Combining them and the walking tour of Stockbridge would create a professional development program for teachers, an adult education experience, and template for what could be done elsewhere. I suspect that every municipal historical organization could identify ten or so documents that highlight the history of their community. In fact the same documents could be taught at different grade levels at different depths and with different related materials to provide on ongoing connection between the student and the community throughout the k-12 years.

Here are a sample of the documents to illustrate the point.

1735 Letter from Konapot and Umpachenee.

A conference was held on January 19, 1735, among 150-200 Mohicans to weigh the decision to move to Stockbridge and to accept the missionary John Sergeant. The decision to approve this was not unanimously supported. Shortly after the meeting, two Mohican men died and many others lay ill. To the opponents of the mission, the deaths revealed the dangers of associating too closely with the English.

An excerpt from the letter in February to Reverend Nehemiah Bull follows which I will not include here.

Think of the questions of facts and discussion which could be generated from this one source and these few sentences. Imagine if the student portfolio contained the comments on the letter as a fourth grade student, middle school student, and high school student. Consider also how such a document and discussion would connect the student to the community. The impact of that decision still affects people today.

1750 King David, Ben Naunauneekanuck and others

The petition is accompanied by a map showing the allocation of the land in the community. The petitioners raise several questions about the way in which the land was granted to the two different peoples sharing the same geographical community. The language of the petitioners isn’t simply in English but in legalese English, meaning the Mohicans had learned how to communicate in the language and ways of the English culture. The map showing the plots means students could identify those lands and determine what is on them today. It is even conceivable that one of plots has remained in the hands of a single family for almost 270 years. Descendants of the original grantees may still be around. Remember the petition was read at the conference by a Stockbridge Indian descendant so there should be Stockbridge English descendants around somewhere as well. The circumstances will vary in the different communities throughout the state, but similar type documents provide a much more “hands-on” connection to one’s community than a state or national curriculum would.

1763 Petition from Konapot and others

This petition held in the Massachusetts archives was the subject of an unfinished painting by Norman Rockwell of Konapot, the same person from the first document, and John Sargeant. I had the opportunity during the afternoon of the conference to view the painting at the Norman Rockwell Museum. While every community might not have a Norman Rockwell or perhaps any artist who depicted scenes from colonial times or other times in the community’s history, the painting in addition to the map in the previous document demonstrates other skills besides reading which can be brought to bear in the presentation of these documents to students.

The petition calls to question the possible shenanigans involved in the calling of a community meeting, the communicating of the date of the meeting to the Mohicans, and the illegitimacy of the person elected at the meeting when one segment of the population was effectively prevented from voting. It should not be too difficult to relate this dispute to issues today.

1783 Letter from John Mtohksin and Others

While I am not going to review each of the documents, this one begins to have national importance. The Stockbridge Indians were allies of the Americans in the war for independence. Their military contribution extended as far south as the Bronx in what is now Van Cortlandt Park. They are part of the story on the American victory in the war. This letter at the conclusion of the war refers to an invitation from the Oneida in New York, another American ally, to relocate there from Stockbridge, MA. That’s how the winning side treated its allies. Move out.

As we begin to gear up for the celebration of the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, one would expect there to be ample opportunity to celebrate all the peoples who contributed in helping the United States prevail. In the meantime, source material such as this letter provides a shift from a more local focus to a more national story yet still told through local materials.

The next document is the more personal memoir of an individual who fought in that war on our behalf. This memoir read by a descendant of her ancestor who felt friendship for his American allies and neglected by them is part of what made this conference session such a moving one. I am sure there are drama clubs in the high schools that could convey the feelings of abandonment and disappointment by this avowed friend of America who risked his life on our behalf. So one can add theater to painting, map reading, and reading to the skills which can be taught through these source documents.

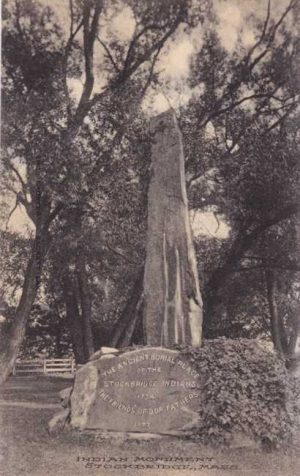

This glimpse into the documents presented is not meant to be all-inclusive history of the community of Stockbridge, MA. Nor is it meant to be an all-inclusive history of the Stockbridge Indians. Their story continues on in New Stockbridge, NY, near the Oneida and onto Wisconsin. But the Stockbridge Indians are proud that they never left the land. One of the documents and one of the stops on the walking tour was of their cemetery and the monument that now stands there. It is located near the municipal cemetery which contains the marked graves of some of the English people in the source documents. Field trips aren’t a frill. They are part of the civic process of connecting people to the land where they live. Every municipality should be able to create such an experience to develop a sense of place, a sense of belonging, a sense of community for its residents.