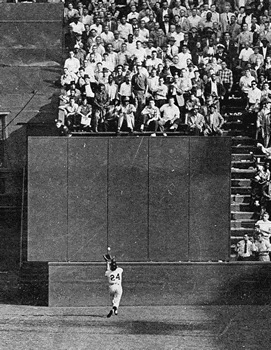

Willie Mays died last week and the celebration of his life continues. His place in Major League Baseball is firmly established. It seems unlikely that we will see another ballplayer like him at least in the foreseeable future. His comparatively injury-free longevity with a single team (even one that moved across country) will be difficult to replicate in this era of free agency and routine injury (Mike Trout).

But there is another facet to his career which deserves special attention. He began his playing career in the Negro Leagues. In my blog We Are Still Here: Negroes and Indians (July 21, 2023), I wrote:

“Remembering when Baseball Was His Calling: The Rev. William H. Greason, 98, aided Willie Mays and was in the last Negro World Series” (NYT 6/5/23/print)

This huge three-page article about the oldest living Negro leagues player obviously abounds in the use of the term “Negro.” It also refers to the Southern Negro League Museum in Birmingham, Alabama.

“In Homage to Mays and the Negro Leagues, M.L.B. Heads to Birmingham” (NYT 6/21/23 print)

Rickwood Field, believed to be the oldest professional baseball stadium in the United States, will host a Major League game on June 20, 2024. This action is part of the celebration by the M.L.B. of Negro League baseball. One hopes that Willie Mays, age 92 and born five miles away, and William Greason, age 98 will witness this stadium where they once played.

Now 11 months later, that blog can be updated. Greason survived and at age 99 was escorted onto the field on June 20. Mays, sadly, did not.

Today it is practically illegal to say the word “Negro.” Consider this example from Columbia University six years ago when it was in the frontlines of the culture wars.

History at Columbia University: Report from a Battle Front in the Culture Wars

April 10, 2018

On April 5, while doing research, I took a lunch-break and picked up a copy of the Columbia Daily Spectator, the Columbia University undergraduate newspaper.

The first article to catch my attention was the front page one entitled “When Professors Make Insensitive Comments, Who Speaks up?” The article recounted the experience of one of two nonwhite students in an American studies seminar last year (apparently the junior year of the student who spoke up). In that seminar the professor informed the class that when studying the 1960s, it was acceptable to use the word “Negroes” to refer to African Americans since that was the term even black people used then to refer themselves.

The student took offense to this usage and communicated it to the professor via email with associated links why the usage was offensive. There was no change in speaking by the professor according to the student and the student subsequently ceased paying attention in class. When contacted by the newspaper, the professor responded:

It is in fact true, as a matter of historical record, that African Americans in the ‘50s and ‘60s wanted to be called ‘Negroes.’ Denying that practice would be a falsification of history.

Willie Mays was born a Negro, raised as a Negro, and had a successful playing career as a Negro. Hence the word was frequently and routinely used in speaking about his life and the league where his career began. The word that frequently cannot be used in the classroom and that teachers (and historians) skip over was used without any sense of apologetic shame or capitulation to woke guidelines. It is not only Louisiana MAGAs with their Ten Commandments in very classroom who are trying to indoctrinate Americans.

As I also reported, on June 27, 2020, the message from Marc Lacey, the National editor of The New York Times, was:

My father was born a Negro. Then he was black. Late in life, much to his discomfort, he became an African-American.

Everyone in this country who traces their ancestors back to Africa has experienced a panoply of racial identifiers over their lives, with some terms imposed and others embraced. In the course of a single day in 2020, I might be called black, African-American or a person of color. I’m also labeled, in a way that makes my brown skin crawl, as diverse, ethnic or a minority.

How can you teach American history by banning the word Negro? For the first two hundreds of existence as a country, Negro was a word used to identify a group of people, none of who self-identified as African America. But while Negro Wall Street became Black Wall Street and the Negro National Anthem became the Black National Anthem, so far the Negro Leagues has been able to maintain its historically accurate name. I predict it will continue to be able to do so.

Is this a contributing factor to the decline in popularity of baseball among African Americans? Of course the usual reasons are given. The game is too slow. The game is too expensive for kids. But somehow these reasons for the lack of popularity of sport ignore its international appeal. Obviously it is popular in Japan. Consider the number of Hispanics in Major League Baseball who can be of any race. The Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Panama, Mexico, and Columbia all participate in the World Baseball Classic along with Puerto Rico. Somehow the reasons for the lack of popularity in mainland United States do not seem to apply to these other countries.

There has to be another reason for the declining popularity among American Blacks. I suggest one reason is that baseball was your grandfather’s game from the time of Negroes. It is a game yesterday best forgotten save for special occasions, an archaic relic from the Negro past. I recall when I attended baseball conferences in Cooperstown, the attendees in the Jackie Robinson sessions for invariably white. It makes one wonder who are the people who are celebrating the Negro League and mourning the passing of Willie Mays.

There is a sense of history in baseball that it is lacking in football and basketball. Consider this title:

“Trying to Reconnect with a Black Fan Base by Celebrating the Past (NYT June 21, 2024 print).

According to the article, Mays grew up in a bygone era. In the 1940s, Sunday church let out early so parishioners could watch the afternoon game with the Birmingham Barons. Overflow crowds packed Rickwood Field, the 114 year old ballpark in Mays’ old West End neighborhood. For decades the field has been a gathering place for the Black community in Birmingham. Now, baseball’s slower pace and reliance on nostalgia seem less cool to younger American sports fans.

Here we may observe the division between Black and white in America. According to Gerald Watkins, the executive director of the non-profit Friends of Rickwood that manages the park:

This is a real field of dreams. It’s not a movie site. And I envision Willie Mays standing in the outfield with a big smile on his face, thinking “Maybe I can get to the big leagues someday.’

The contrast between the two fields tells the tale of America. The Iowa field wasn’t even a baseball field until Hollywood made it one. It was a story of the redemption of Shoeless Joe Jackson nearly a century earlier. More importantly is was a story of a father and son reunion as James Earl Jones memorably intoned on the wonder of baseball in American culture on the land of a picket-fence white American family. The father and son playing catch has been known to bring tears to adult males.

By contrast this real field of dreams has had its brush with Hollywood. It has served as the playing field for movies about Ty Cobb and Jackie Robinson. But it has not become the tourist site the fake Field of Dreams has become as a place where a father and son can have a catch.

Will things change now? Will football and basketball fans visit the site of living field of dreams from another sport even if it helped made modern professional sports possible? Unlikely. After all, what history sites attract the football and basketball fans today? Instead this somewhat decaying structure like so many historic sites in this country will continue on drawing the faithful without ever becoming a national destination site. Now imagine if LeBron James and other star athletes from the present had paid homage to the Negro past instead of not even being able to say that word.