Can Alexander Hamilton once again ride to the rescue of America? This overblown claim deserves a second look. In previous posts, I examined the impact of the new musical Hamilton in an America with a desperate need for a We the People story that transcends the hyphenization now running rampart in our society.

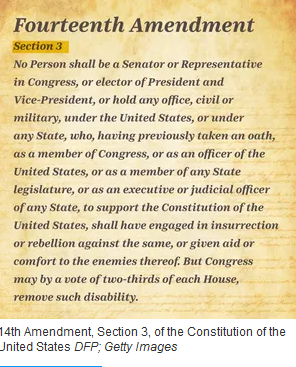

For Americans, authenticity means being true to the Constitution, an evolving document which was amended in the beginning, throughout American history, and which can be amended again.

I ended my last post with a query imagining if high school students would perform Hamilton instead of (or in addition to) Grease (West Side Story and the other teenager-based musicals).

As it turns out, that process may already be underway. Rand Scholet, president of The Alexander Hamilton Awareness Society, recently attended a special performance of Hamilton. In an email to the Society, he reported that:

“the “Hamilton” cast & crew did a matinee show for students from a number of high schools. The response was thunderous and even moved the performers more than usual. We know this because a talk-back session with “Hamilton” creator Lin-Manuel Miranda, musical director Alex Lacamoire, and key cast figures was held after the show. High schools across the nation are already asking for a version of the show for their high school musicals.”

Two authors participated in that event: Ron Chernow, author of the biography Alexander Hamilton that inspired the musical and Richard Brookhiser, author of Alexander Hamilton, American, who was in the audience doing a review on the musical for a national magazine.

In a book review on Chernow’s George Washington, Gordon Wood wrote:

“Chernow is an outstanding member of the new breed of popular historians who dominate narrative history-writing in the United States today. Independent scholars such as Chernow, David McCullough, Walter Isaacson, Jon Meacham, Thomas Fleming, Stacy Schiff, Richard Brookhiser, David O. Stewart, James Grant, Eric Jay Dolin, Barnet Schecter, and others do not have Ph.D.s in history and possess no academic appointment. They are not engaged in the conversations and debates that academic historians have with one another, and they write their history not for academic historians but for educated general readers interested in history. This gap between popular and academic historians has probably existed since the beginning of scientific history-writing at the end of the nineteenth century, but it has considerably widened over the past half-century or so.”

For a current example of this phenomenon consider Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania by Erik Larson. In an interview he commented:

“It is my goal to create a historical experience with my books. My dream, my ideal, is that someone picks up a book of mine, starts reading it. And just lets themselves sink into the past and then read the thing straight through, and emerge at the end feeling as though they’ve lived in another world entirely.”

To accomplish this non-academic goal, Larson engaged in some academic activities. He read through the archives, the primary source materials in multiple countries but he modeled his narrative arcs and prose style on fiction. The results have been books that have been best sellers and part of school curriculum.

Add Lin-Manuel Miranda to this list of popular historians as he did what these authors did only to create a product in another medium: He read the primary source documents, he visited the historic sites, he researched the subject. As he said, “I want the historians to respect this.”

The issue of academics writing narrowly-defined studies for other academics results in narrative story-telling being left to others. And since we are a story-telling species, those narrative stories tend to be about individual people with larger-than life stories to tell. In my posts on the American Revolution Reborn conference in Philadelphia in 2013, I cited Annette Gordon-Reed, author of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy, saying that people want a narrative, that the story is what people respond to. I also wrote about the academic disdain expressed at the conference for “airport best-selling biographies”. I then raised the question that the American Revolution reborn story is needed but that the new national narrative has to be coherent and connect to the American people so they have a valid stake in the story. Is the academy up to the challenge?

The answer would appear to be “No.” Lin-Manuel Miranda, however, is up to the challenge.

As it turns out, Miranda first graced the pages of my posts to New York History nearly three years ago, when I wrote:

Miranda asked: “Why hasn’t anyone done a hip-hop version of Alexander Hamilton’s life?” What sparked Miranda’s interest in Hamilton, a Caribbean immigrant to New York who established the economic foundation for this country and not Jefferson? A paper he wrote in high school about the duel with Burr. Later as an adult he read Ron Chernow’s biography of Hamilton while he was on vacation in Mexico. (What do you read when you travel?) Miranda then answered his own question by creating “The Hamilton Mixtape,” a hip-hop song cycle based on Hamilton’s life, excerpts of which were played at Lincoln Center. That’s America. That’s why education is so important. That is why the new social studies curriculum is so important for our future.

Interestingly, the articles about Miranda tend to mention his reading of the Chernow book without taking it back a step to ask why he chose that back. It turns out it was a high school assignment.

These issues of curriculum, citizenship and identity remain important three years later. Now that the mixtape is a musical, it addresses the issue of an American Revolution Reborn narrative in a way the conference could not. At Fraunces Tavern, the non-white Leslie Odom, Jr., who plays Aaron Burr, said: “When I think about what it would mean to me as a 13-, 14-year old, to get this album or see this show — it can make me very emotional.”

One may observe here the new national narrative being born. As The New York Times columnist David Brooks put it:

“[Hamilton] also left behind a spirit — the spirit of grand aspiration and national greatness. The cast … is mostly black and Latino, but exudes the same strong ambition as this dead white man from centuries ago. America changes color and shape, but the spirit Hamilton helped bring to the country still lives.”

Or as Rebecca Mead in The New Yorker wrote:

“Lin is telling the story of the founding of his country in such a way as to make everyone present feel they have a stake in the country….By telling the story of the founding of the country through the eyes of a bastard, immigrant orphan, told entirely by people of color, he is saying, ‘This is our country. We get to lay claim to it.’ [bold added]”

This was the message the academic American Revolution Reborn conference was not designed to deliver. This is a story for America’s youth, for America’s future. The American Revolution will be reborn for the 21st century and Hamilton will become a heroic Founding Father to Americans once again.

Excellent and thought provoking blog Peter, If you are suggesting, as you seem to in one part of your essay, that only academically credentialed historians can write true history, I believe the examples of the work of popular historians such as Ron Chernow and Rand Scholet on Hamilton you cite indicate that this is a significant error. I believe this is an

old argument and one which was rejected by no less a popular historian as Theodore

Roosevelt in his Presidential address to the American Historical Association on December 27, 1912,at its Boston convention (Roosevelt was apparently the only historian to serve as both President of the Unites States and then President of the AHA). To my knowledge, although he attended but did not graduate from Columbia Law School, he never held an academic history degree.

In any event an interesting question you also raise, which has increasingly fascinated me, is why certain historical figures such as Hamilton at this point in time receive such historical acclaim, while others are almost completely forgotten. For example, General Horatio Gates, hero of the Battle of Saratoga, Marinus Willett,

who among other things was a founder of the New York City Democratic Party

settled the Creek War in 1790, and rallied the New York militias in the War of 1812,

and Albert Gallatin, one of Hamilton’s longer serving successors as Secretary of the Treasury, are all buried within 100 feet of Hamilton in Trinity Churchyard, but very few if any New Yorkers know who they are. Perhaps if our schools in their social studies classes covered these individuals there will in the futureI be best selling popular plays and hip hop musicals about them.

James S. Kaplan

President, Lower Manhattan Historiacl Society