In May, a controversy over a college role-immersion game went public. The game is part of Reacting to the Past. The specific application is the Frederick Douglass game set in 1845. That game has now been pulled. At this point, I am not sure if the controversy has subsided or if it is simply the end of the semester and the Memorial Day holiday weekend when people have better things to do than blog.

MINDS ON FIRE: HOW ROLE IMMERSION GAMES TRANSFORM COLLEGE

Back in August 2014, I read a review by Steven Mintz, University of Texas, of this new book by Mark Carnes, Barnard College. I printed the review because of its storytelling basis. As a longtime proponent that we are a storytelling species and that history museums should use stories more to convey the history of their site, naturally I was intrigued by this collegiate approach. I never did get around to writing a blog about it and now I will do so.

The issue the games sought to address is the lack of engagement by college students in the history material being presented in class. The proposed solution was a collaborative game that immersed students in the historical situation being studied. The book reviewer began by reporting on problems being experienced in the undergraduate experience at that time. Specifically the failure to set students’ “minds on fire” was cited.

The proposed remedy from Carnes was to “tap the motivational power of play.” The reviewer noted the intensity, competitiveness, and subversive elements of play according to Carnes. The immersive games could “shock us out of sheep-like passivity.” Possibly his use of film in the classroom contributed to his undertaking this new application. In 1995, he launched “Reacting to the Past.” Students debated fundamental issues from pivotal historical episodes by assuming roles informed by classic texts. By 2014, over 350 institutions used the game.

For the game to succeed, faculty needed to step back from their traditional professorial persona and allow the classroom to be student-run. Instructors were guides on the side and not sages on the stage. They were umpires watching the game play out before them. The book presented Carnes’ proof that after nearly 20 years, the approach worked. Student engagement, motivation, and familiarity increased along with the development of empathy. Essentially, they were not simply walking a mile in someone’s shoes, they were speaking with someone’s mouth and therefore learning how that person thought.

The reviewer responded positively to the “promoting students’ affective development, interpersonal skills. Moral reasoning, and psychological maturation…in cultivating cognitive growth.” Empathy and community ranked high on the skills developed.

Yes, there were the issues of forcing students to speak publicly and to defend ideas contrary to their own. Overall, the reviewer accepted that rigorous external assessments indicated that gamification works for highly diverse subpopulations of students including recent immigrants and students struggling with the English language.

The review concluded with:

I hope that historians will carry away certain essential lessons from Carnes’s book: That students often learn more when instructors teach less; that classroom competitions can often instill a sense of community; that students better understand themselves when they assume the identity of historical actors; and that students’ moral reasoning strengthens most when they must wrestle with ethical dilemmas without a teacher’s intervention. Carnes’s most important message, however, is the one faculty find easiest to forget: That a college education is not about the instructor’s intelligence, insights, or eloquence; it should be about student learning.

Times were more innocent in 2014.

COLLEGE PROFESSORS DROP SLAVERY ROLE-PLAYING LESSON OVER CONCERNS IT UPSETS STUDENTS

In the May 14, 2022, print edition of the Wall Street Journal this article was published with the title “Slavery Role-Playing Lesson for Colleges Taken Off Market” (Douglas Belkin). The online version added the subtitle: “Reacting to the Past [the Company] removed its Frederick Douglass game from print after concerns at some of the 500 schools that use its historic debate series”.

The action was taken in response to concerns expressed by students and professors who objected to advocating for white supremacy in the playing of the game. I do not know what all the 30 available games are, but this one with Frederick Douglass is the one that sparked the controversy. This game has as many as 75 characters including Sojourner Truth and Robert E. Lee. About 1000 copies per year are sold making it one of the bestsellers. However, according to Nicolas Proctor, editorial board director, in an email to one of the game’s co-creators:

Racist speech can easily create an unsafe environment. It “can be demoralizing and triggering, particularly for African-American students.

The co-creators declined the request to make changes in response to the complaints:

They are scared to death of confronting racism in American history because it could blow up in their face. They want to rework it and take out all the controversy and leave it as a viable game but there is no way to do that.

This was the reply of Mark Higbee, history professor at Eastern Michigan University and co-creator of the game along with James Brewer Stewart, professor emeritus at Macalester College.

The article concludes with the example from the class of Mark Thompson, California State University. The student is David Castillo who describes himself as white, Mexican and Japanese. In the game, he portrays a New York City dockworker who disapproves of both slavery and Black people. His character also thinks women shouldn’t express an opinion. In the game, he interrupts classmates playing Black people by calling them animals. He urges women to shut up.

Castillo acknowledges that he was initially a little uncomfortable insulting his classmates but likes the game because he thinks it forces students to think about points of view that they may not have previously considered and with which they don’t agree.

The central question of the game is to ask yourself, ‘How can these characters believe what we can’t believe they believe?’”

One might add learning how one can believe the election was stolen, COVID is a hoax, and the vaccines are worse than the fake virus or vice versa depending on your point of view.

REACTING TO THE CANCELLATION OF REACTING TO THE PAST

Ironically, the first reaction I read was from a professor who had not used the game. Jack McKivigan, is the editor of the Frederick Douglass Papers at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis. He asked for student volunteers to read Douglass’ texts as part of the biannual Douglass symposium held on campus. He was met with a “well-organized and effective boycott.” He concluded,

There may be a growing discomfort to even acknowledge the embedded racism in our nation’s history that goes beyond current political correctness debates. Removing one-half of the history of racism as Reacting to the Past seems to be doing could very well lead to erasing the other-half in the interests of keeping our (white) students guilt-free and comfortable–or better, “comfortably numb.” (May 13, 2022)

As we know from the 1619 and CRT controversies, white people object to “divisive” curriculum that disparages them on the basis of their race.

McKivigan’s comment led to a response by co-creator of the Douglass game, James Stewart (May 14, 2022):

The final sentence of your disturbing post captures perfectly my deepest concern about the decision to cancel Mark Higbee’s and my FREDERICK DOUGLASS, THE CONSTITUTION AND THE PROBLEM OF SLAVERY– In this case the fact that fully credentialed historians unilaterally cancelled the scholarship and pedagogy of their colleagues and peers because, as one such censor put it, it addresses the problem of slavery (this is the literal quote) “too forthrightly”.—- .

How, one might ask, can historians stand strong against the likes like Ron DeSantis let alone enlighten “comfortably numb” students if they willingly censor themselves, or worse still, one another?

After another round of exchanges and the mass murder in Buffalo, Stewart wrote:

At the same time my approach to student Fragility/ Intractability has always been to stand my ground and insist that the “tough stuff” (quote from the late, much lamented James O. Horton) must be confronted as honestly and amply as possible. If I fail to convince them, it’s on them, not me to defend their beliefs right there, on the spot, in class. And if that leads to complaints to higher ups, that’s just fine by me. Serious change requires conflict that generates heat as well as light. Just as was the case for the original abolitionists, it’s controversy, not concessions, that moves us forward.

At this point, Mark Carnes chimed in (May 20, 2022):

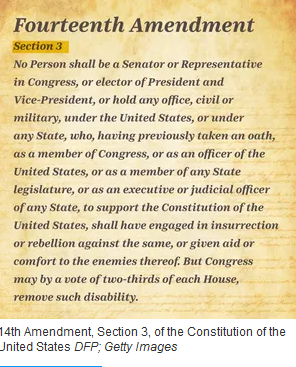

Proctor explained that the chief issue for the REB concerned the voicing of pro-slavery positions by students. “Racist opinions must figure in any historical account of the antebellum era,” he observed, “but the Board maintained that we should not require students to voice the idea that slavery benefited enslaved peoples, or that people of African descent are inherently inferior to whites.”

“The Reacting pedagogy seeks to put students in the shoes of historical figures, even those whose views students may find disagreeable or even repugnant. This sharpens critical thinking skills and promotes historical empathy,” Proctor added. “The editorial board believes that the Douglass game is powerful, but that it needs to provide more scaffolding and more options so that instructors and students can engage with these ideas in ways that do not have the potential for serious harm.”

The co-creators replied to this explanation. Be warned that they pulled no punches.

That’s because (much to our surprise) it [your explanation] buttresses our conclusion that your decision was driven by fears of White fragility, Black backlash and White supremacist manipulation.

Cut through your explanations of bureaucratic decision making (and the promotion of your Reacting book series) and your account confirms what we already know…You cancellers were to become our peer reviewers! Predictably, we walked away from your offer.

Why such adamancy and inflexibility on your part? Because, as messages to us from your close colleague Nick Proctor make clear, you feared that our book’s antiracist pedagogy “can create an unsafe environment…[be] demoralizing and triggering particularly for African American students…. May provide an avenue of attack by racist revisionists….” In short, you silenced us because our pedagogy is, in your “politically correct” view, excessively antiracist.

Finally, in your post you quote your associate Nick Proctor’s statement that “The [Reacting to the Past Editorial ] Board maintained that we should NOT REQUIRE STUDENTS to voice the idea that slavery benefited enslaved peoples, or that people of African descent are inherently inferior to whites.”

We state categorically that our pedagogy DOES NOT REQUIRE students to voice proslavery opinions. Those who elect do so are volunteers, not conscripts. Proctor’s claim to the contrary is patently untrue. You can consult our book to confirm this for yourself.

The exchange ends (for now) with a zinger from co-creator Mark Higbee (May 23, 2022):

But the RTTP bureaucracy lacks transparency and accountability to anyone outside of its little circle.

These are facts:

1. This decision to cancel the very successful Douglass book was NOT based on any data, but on fears of what “may” happen when students & instructors use the book. (If Drs. Carnes & Proctor had data, they would have provided it when Jim and I asked for it.).

2. The RTTP leadership’s decision to cancel Douglass is arrogantly meant to violate the academic freedom of Reacting instructors, because it’s meant to deny them the opportunity to use the book in class.

3. Jim and I will update the book, with another, braver publisher. This will take time! Meanwhile, instructors have our permission to photocopy the book for their students! Email me for Characters/roles for your class, at mhigbee@emich.edu. (Or even for a copy of the existing book). …

5. All that has changed [since 2019] is that some in academia are more cowardly when it comes to confronting racism in classrooms on campus. Sadly RTTP is now controlled by such people, who oppose anti-racist pedagogy.

6. Lastly, please know that this cancellation of a successful book is an extraordinary act by the sponsors of an academic book series. It was unexpected, out of the blue. No complaints about the book had been expressed to Jim or me since its publication in 2019, until Feb. 15, 2022. Not by RTTP leaders or the book’s users in classrooms across the country. Reacting instructors defended the book, but were ignored.

Frederick Douglass will continue to advance the cause of equality and education!

On this defiant none, the exchanges ceases. The story is not yet over.

The fight over the teaching of history has not ceased. It will continue to grow and fester as we approach the 250th anniversary of the birth of this country. Of course by the time that date arrives, the two sides may have withdrawn to their separate corners, i.e., countries.

I retired in May of 2019, so have escaped the worst of such so-called “controversies” (as if there are two sides). Many years ago, in “more innocent times,” I had classroom debates over slavery, and to my surprise a young black woman took on the pro-slavery role. She did a very good job — in my later letter of recommendation I described as attesting to her character, courage, and flexible mind. Also, in my Civil War and Reconstruction course I routinely assumed pro-slavery literature (the kind that justified slavery on how kind the masters were), avoiding the insulting type that, as far as I know, was not reproduced for classroom use. College education is supposed to confront students and make them think, removing teaching devices because of fear that either black or white students will be insulted or made to feel guilty is a surrender of education itself.

You were operating out of a come-let-us-reason together environment where understanding the “other” was crucial to the development of critical thinking skills. Today people are more sensitive and function in a zero-sum universe where the enemy “other” is not fully human and must be destroyed just as people tried to do in real wars.

“students often learn more when instructors teach less”

I’m skeptical about that. When I’ve encountered that philosophy in classrooms, it was from instructors who didn’t like teaching and/or weren’t any good at it, and it gave them an excuse to do little or nothing while pretending to do something. Such instructors should be paid accordingly, and students (and whomever is paying for their education – parents, grant agencies, etc.) forewarned before registering for such a class – which should never be a class that is required.

Sometimes “proof” in favor of such methods collapses under examination, not surprising when what’s offered as proof comes from the creators themselves tooting their own horns. The proprietary “Team-Based Learning” boasted how the group Team Readiness Assurance Test scores being higher than Individual Readiness Assurance Test (IRAT) scores helped demonstrate its effectiveness. But group scores could be increased by (1) people agreeing to go with the answer of the best-prepared/smartest student, (2) getting partial credit if their second or third guess on a scratch-off card as to the correct answer turned out to be the right one, (3) someone in the group making a good case as to why their “wrong” answer should be considered acceptable. Since those options weren’t available in the individual tests, then of course the group scores would tend to be higher, regardless of whether people were really learning better as a group or not. (Also, if students read the book about TBL they’d know they could shine an ordinary laser pointer through the card to determine the correct answer, scratch just that one, and thus get full credit by getting the correct answer on the first try.)

With respect to the role-playing game specifically, though – I have trouble seeing that really working. How many students go into acting, or active role playing games (as opposed to passive ones like video game RPGs), or clubs like the Model United Nations. Relatively few. Even as someone who has in the past played some of those games, had been in the Model UN, and has been a film extra occasionally, I wouldn’t care to essentially have a starring role acting by playing Reacting to the Past. Instructors are really prepared to teach acting, and act as directors? Nuanced characters will exist in addition to cartoonish, stereotyped ones? Severely shy, socially phobic, or autistic students will be just fine? I have my doubts.

You raise a number of important points. First, the key to good teaching is the teacher so results may vary. Second, the differences between those who do participate and those who don’t need to be accounted for. Third, people quickly learn how to game the system. Thanks for writing.

I find story telling works really well and is appreciated in place of s names and dates drop !

This game also was about role-playing and voicing opinions in contradiction to a personal belief.

I really appreciate your emailing this last blog, and of course Frederick Douglass caught my eye, as I so respect and admire everything about him!

This college form of “role playing” (my interpretation) seems most valuable to that age group as in a “You are THERE” imaginary situation. Do “resistors” believe that young adults “can’t handle this”? Whatever happened to using one’s personal and community imagination to discover history?

Let me know how this turns out, and THANKS for fighting the “water-down history crowd” as I see it.