400 years is in the news. The time period has been the topic of some tweets and interviews by Kanye West in relation to slavery in the United States. Putting aside the Emancipation Proclamation, the 400 year time period of Middle-Passage blacks in America calls to mind other 400 year periods in American history.

- In 1893, America celebrated the Columbus quadricentennial one year late in a famous exposition in Chicago

- In 2007, Jamestown celebrated its quadricentennial including a royal visit from England

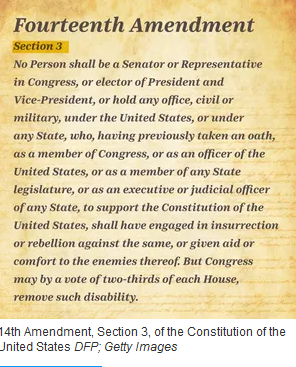

- In 2009, New York, Vermont, and Canada celebrated the quadricentennial of Henry Hudson and Samuel Champlain including a royal visit from the Netherlands

- In 2011, Protestants especially in the United States and the United Kingdom celebrated the quadricentennial of the publication off the King James Version of the Bible.

400 year anniversaries are a big deal. They involve long memories and cultural continuity.

In biblical terms, the 400 year time period is well known and for its connection to slavery:

Then the LORD said to Abram, “Know of a surety that your descendants will be sojourners in a land that is not theirs, and will be slaves there, and they will be oppressed for four hundred years (Genesis 15:13).

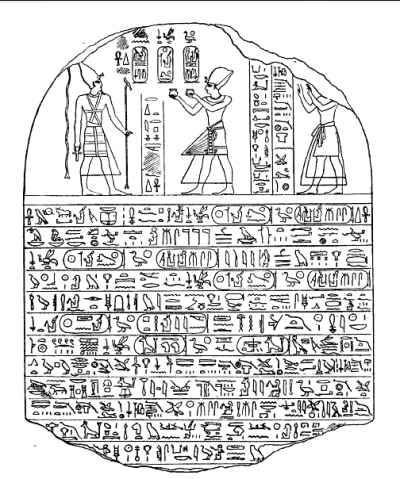

But is not the only 400-year period known from ancient times. As it turns out there is another memory of a 400-year period and from Pharaoh Ramses II, the traditional pharaoh of the Exodus. Ramses II honored the legacy of the Hyksos in Egypt commemorating their sojourn in the land in year 400, month 4, season 3, day 4 on an artifact appropriately called the Four Hundred Year Stele. The idea that there is a connection between these two 400-year traditions from the 17th to 13th centuries BCE involving West Semites in the Delta in the time of Ramses is not new. The connection between the two cultural memories was the subject of my paper last November at the annual conference of the American Schools of Oriental Research (to be published as “The Hyksos and the Exodus: Two 400-Year Stories,” in Richard Beal and Joann Scurlock, ed., What Difference Does Time Make? [Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns]).

Let’s examine the significance of the number and then turn to the issue of connections. To begin with there is the number four. Assyriologist Piotr Michalowski observes:

Not to be content to be kings of Sumer and Akkad, these [Akkadian] rulers added still another forceful epithet, “king of the four corners of the universe,” or, in Sumerian, “kings of the heaven’s four corners,” in a sense driving home the notion of “everything.”1

This sense of “everything” through the use of “four” continued across the millennia in Mesopotamian times from Akkadians to Assyrians.

Four certainly is known in the biblical tradition and in the same cosmic sense. There are the four rivers of the garden encompassing the world (Gen. 2:10). There are the four cities Nimrod rules encompassing the empires from in the beginning to the present of the author if one dismisses Egypt (Gen. 10:8-10). There are the four kingdoms of chaos who are defeated by the warrior-shepherd(/king) of Hebron in this version of the cosmos and chaos tradition (Gen. 14). And there are the four kingdoms in the Daniel tradition (Daniel 7:2-7) thereby raising the perennial question of who would be the fifth kingdom. These examples all attest to the cosmic dimension of the number 4 and its sense of completeness.

Raising the number four by a factor of ten continues the metaphorical not literal dimension of numbers. Forty also is number well-known from the biblical tradition in a variety of examples and settings. It rains for forty nights and forty days (Gen. 7:4, 12, and 17; 8:6). Israel wanders in the wilderness for forty years (Ex. 16:35; Num. 14:33-34; 32:13; Deut. 2:7; 8:2, 4; 29:5; Josh. 5:6; Neh. 9:21; Ps. 95;10; Amos 5:25; Acts 13:18; Heb. 3:9, 17). Moses and Elijah were on the mountain for forty days and forty nights (Ex. 24:18; 34:28; Deut. 9:9, 11, 18; 10:10; I Kings 19:8). There are additional examples of the use of forty as well.

The extensive use of the number 40 across a wide range of times, people, and circumstances suggests some intrinsic value was associated with the number 40 beyond a literal meaning. My sense of the usage is that 4 x 10 also implies a totality, the completion or fulfillment of a measure of time, a way of marking periods or cycles, and is not to be taken literally. It signifies the right amount in time or for an action. God forbid Hazael should have brought 41 camel loads (II Kings 8:9) or Moses and Elijah should have remained on the mountain top for only 39 days and nights. Those actions would have disrupted the cosmic order. The audience expected 40.

The number 40 also is attested outside the biblical narrative. In the Mesha Stele, Mesha, the king of Moab, declares that Israel had ruled over the land of Moab for forty years.

Omri had taken possession of the land of Medeba, and dwelled there his days and much of his son’s days, forty years.

The more challenging question is to determine how it came to be that Mesha used the same number used so frequently in biblical accounts. In this regard, the task is similar to that between the two usages of 400 by Ramses and the story of oppression in Egypt ending with Ramses. The idea that there is no connection between the biblical 40 and 400 and the non-biblical usages by Mesha and Ramses would be considered farfetched in any discipline other than biblical studies.

Ramses didn’t only use 400 years in the appropriately named “Four Hundred Year Stele.” He also used 4 for the day and the month. He probably would have used four for the season too except Egypt only had three. Egyptologist James Hoffmeier characterizes this dating as “odd, raising the possibility of some sort of symbolism.”2 The stele commemorates the action of his father Seti I infusing the Baal-Seth identity in the new Egyptian capital at Avaris at the birth of the new dynasty. In a sense, the action officially demarcated the cessation of the Amarna Era (chaos) and the primacy of the Baal-Seth deity at Avaris (order) over the Amun-Re deity at Thebes in the 18th Dynasty. All these machinations automatically have political overtones. While the politics of the birth of the 19th Dynasty are beyond the scope of this post, one should remain cognizant that those developments form the backdrop to the Four Hundred Year Stele.

Again my sense is this higher factor of 4 and 102 signifies a unit of completion or perfection. In this case, Ramses is referring to a period of time or cycle that presumably has now concluded. I propose that in the Four Hundred Stele, Ramses sought to merge the two traditions as his father had. The time of the onset of the new Egyptian dynasty was the time of the completion of a period in history. He integrated the Hyksos timeline into the Egyptian one. Instead of the Hyksos ruling during an “intermediate period” as in Egyptology today, the Hyksos were the beginning of a cycle which concluded with the post-Amarna restoration. What had been separate now became one. Baal began both periods in history. From this point forward, the two peoples were chronologically merged into a single timeline in Egyptian history. It was morning in Egypt. Here comes the sun on a new day in Egyptian history. Ramses had delivered a political message in his present through the metaphorical values of the numbers he chose to publicly proclaim in the organization of temporal epochs.

Egyptologist Hans Goedicke dates the Four Hundred Year stele to shortly after year 34 in the reign of Ramses. He asks:

Why should Ramses in the second half of his reign suddenly have an urge to foster the legitimacy of his rule and that of his family, after they had occupied the throne for more than fifty years?3

I propose that the origins of the stele are to be found in the aftermath of the Battle of Kadesh during the reign of Ramses II.

This famous battle between Egypt and the Hittites in Year 5 of the reign of Ramses II is famous for important reasons:

- the size of the armed forces in a Bronze Age battle was huge and rare

- the numerous descriptions of the battle in image and text by Ramses II

- the existence of an alternate vision of the battle by the Hittites

- the ineptitude of the new Pharaoh in falling into a trap

- the rescue of Ramses by a Semitic military contingent

- the motifs used by Egypt which could be appropriated by others for their own purposes.

Just as Waterloo and D-Day live on in the cultural memory of western civilization so too Egypt’s two main battles in the Levant, Thutmose III at Megiddo and Ramses II at Kadesh lived on in the cultural memory of the Canaanites.

There were geopolitical consequences to the battle. Egyptologist Donald Redford claims that after the battle of Kadesh:

Headmen of Canaanite towns, vassals of Egypt, were impressed by what they divined as inherent weaknesses in Pharaoh’s forces: poor intelligence and a tendency to panic. Rebellion was possible; Egypt could be beaten….In the wake of the retreating Egyptians, all Canaan flared into open revolt….It was Ramesses’s darkest hour.4

Redford limits this awareness to Canaanites in the land of Canaan. Redford is correct about Canaanites revolting in the land of Canaan following Ramses’s poor performance as commander in chief. The destruction in Hazor is simply the most prominent example of the “Canaanite spring,” the unrest Ramses now had to face in land of Canaan.

Meanwhile, all was not quiet on the home front either. As Thomas Thompson astutely comments on the significance of the battle of Kadesh beyond the battle itself.

After this defeat, Ramses II’s army was racked with revolts. It had borne the brunt of the cost of his expensive misadventure….Civil unrest and religious opposition at home was doubly encouraged….A series of plots and intrigues by court factions bitter over the military failure at Kadesh effectively paralyzed royal authority and its control of import groups within the army.5

One might take issue to the extent to which unrest and intrigue occurred, but the basic thrust of the observation appears valid. Kadesh exposed the shortcomings the leader of the country and people responded to that weakness. Thompson has honed in on the precise time when the potential for disruption of ma’at in the political arena had occurred.

I propose that that it was this very disruption which led to the two 400-year traditions in Egypt and Israel. Baruch Halpern suggests that if the Israelites scribes knew the 400 Year stele, that such knowledge is evidence of the portrayal of Israel as Hyksos and the identification of Ramses as the Pharaoh of the Exodus. He asserts the Israelites linked themselves to the memory of the Hyksos in Egypt probably during the time of Solomon when relationships between the two countries were good and monuments were being relocated from Goshen/Avaris to Tanis where the 400-year stele ultimately was found.6 He does not appear to consider the possibility that the some Hyksos actually led the people who left Egypt in the time of Ramses II and that therefore these linkages were always part of the Israelite cultural heritage right from the start. After his failure at Kadesh and the departure of Hyksos Levites and others to liberate the land of Canaan from Egyptian hegemony, Ramses sought to shore up his support with the Hyksos who had remained in the land with the Four Hundred Year Stele. The Hyksos Levites who had left Egypt after the Battle of Kadesh and then became Israelite later incorporated that event into their own cultural memory. After all, they too had been in the land of Egypt for 400 years before they left. Once you realize that the Levites were Hyksos all the pieces fall into place.

Notes

- Piotr Michalowski, “Masters of the Four Corners of the Heavens: Views of the Universe in Early Mesopotamian Writings,” in Kurt A. Raaflaub and Richard J.A. Talbert., ed., Geography and Ethnography: Perceptions of the World in Pre-modern Societies (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 147-168, here 153.

- James K. Hoffmeier, “What Is the Biblical Date for the Exodus? A Response to Bryant Wood,” JETS 50 2007:225-247, here 238n.74.

- Hans Goedicke, “Some Remarks on the 400-Year Stela,” CdE 41 1966:23-37, here 24.

- Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 185.

- Thomas L. Thompson, The Mythic Past: Biblical Archaeology and the Myth of Israel (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 153.

- Baruch Halpern, The Exodus from Egypt: Myth or Reality,” in Hershel Shanks, William G. Dever, Baruch Halpern, P. Kyle McCarter, The Rise of Ancient Israel: Symposium at the Smithsonian Institution, October 26, 1991 (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeological Society, 1992), 86-117, here 98-101; and Baruch Halpern, “Fracturing the Exodus, as Told by Edward Everett Horton,” in Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider, and William H. C. Propp, ed. Israel’s Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective: Text, Archaeology, Culture, and Geoscience (New York: Springer, 2015), 293-304, here 299.