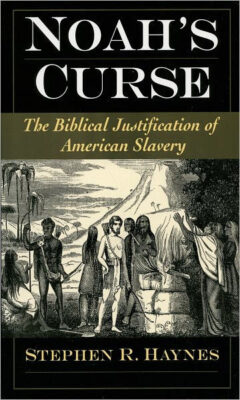

The current issue of Biblical Interpretation includes the article “The Blessing of Ham: Genesis 9:1 in Early African American Biblical Scholarship” by Jeremy Schipper, University of Toronto. The use of the Bible on both sides of the slavery debate leading up to the Civil War is well known. Since this article appears in a biblical publication and is by a biblical scholar, it is quite possible that American historians might overlook it.

The article focuses an exegetical arguments made by James W. C. Penning, Alexander Crummell, Benjamin Tucker Tanner, and George Washington Williams from the 19th century about Noah’s curse of Canaan and its meaning for slavery and race.

BIBLICAL VERSES

The main biblical passage in question is Genesis 9:20-27 following the flood:

Genesis 9:20 Noah was the first tiller of the soil. He planted a vineyard; 21 and he drank of the wine, and became drunk, and lay uncovered in his tent. 22 And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brothers outside. 23 Then Shem and Japheth took a garment, laid it upon both their shoulders, and walked backward and covered the nakedness of their father; their faces were turned away, and they did not see their father’s nakedness. 24 When Noah awoke from his wine and knew what his youngest son had done to him, 25 he said, “Cursed be Canaan; a slave of slaves shall he be to his brothers.” 26 He also said, “Blessed by Yahweh be Shem; and let Canaan be his slave.” 27 God enlarge Japheth, and let him dwell in the tents of Shem; and let Canaan be his slave.”

Observant readers will note that:

1. Although Ham is the one who committed the inappropriate action, it is his son Canaan who is cursed;

2. God (Yahweh) does not issue the curse, human Noah does.

Also figuring in the analysis is the settling of world by the three sons of in the following chapter in the Book of Genesis referred to by scholars as the Table of Nations:

Genesis 10:6 The sons of Ham: Cush, Egypt, Put, and Canaan.

These designations place the sons of Ham in Cush (Nubia), Egypt, Put (scholars debate whether Libya or Punt is meant and exactly where Punt is located probably in south Sudan/Eritrea area), and Canaan which is not in Africa.

This division is followed by the Tower of Babel story in the next chapter of Genesis. For more about these stories see my book Jerusalem Throne Games: The Battle of Bible Stories after the Death of David (Oxbow Books).

BACKGROUND

Schipper begins with the book The Myth of Ham in Nineteenth Century American Christianity: Race, Heathens , and the People of God by Sylvester A. Johnson (2004). The thesis is that the “myth of Ham” was used in the 19th century to explain racial origins and not to justify or condemn slavery. He does not include a close examination of how scholars understood the relationship between the myth in Genesis 9 and the dispersion in Genesis 10.

Schipper’s article intends to fill that void by examining four of the people Johnson mentions in his book. His contention is that Ham shared the divine blessing with his brothers from the previous pericope:

Genesis 9:8 Then God said to Noah and to his sons with him, 9 “Behold, I establish my covenant with you and your descendants after you,

which goes on to include the famous bow in the clouds as a sign of the eternal covenant, hence the title of the article “The Blessing of Ham.” That divine blessing is separate from the human Noah’s curse in Genesis 9:20-27. That curse only appears here in the Bible and nowhere else.

JAMES W.C. PENNINGTON AND THE BLESSING OF HAM

Pennington was the first African student at Yale. After receiving a Doctor of Divinity from the University of Heidelberg, he became pastor of the Fifth Congregational Church in Hartford. In 1841, he published A Text Book on the Origin and History &c. &c. of the Colored People which is available online and I downloaded. According to Schiffer, Pennington’s book provides the earliest example of the argument that the people of African descent are not under Noah’s curse but share the divine blessing Ham had with his brothers.

Schipper observes the effort to counter the racist pseudo-scientific ideas that Africans are not full human beings. White theologians in the early 19th century celebrated the intellectual and cultural achievements to world history made by descendants of Cush, the son of Ham.

Pennington writes that the curse by Noah was levied against Canaan and not Ham or his other son Cush. Africans are not Canaanites so they were cursed neither by God nor Noah.

ALEXANDER CRUMMELL AND THE BLESSING OF HAM

Crummell was an Episcopal priest and graduate of Queen’s College, Cambridge. In 1863 he published an essay “The Negro Not Under a Curse: An Examination of Genesis ix 25” which is available online in his book The Future of Africa which I also downloaded. The earlier version appeared in The Christian Observer 153 (September 1850), 600-607.

Crummell’s contention also is that Noah cursed Canaan and that Canaanites are not associated with Africa. As reported by Schipper, Crummell argues that a human curse cannot override a divine blessing. Crumell goes on to cite the biblical verse on the sons of Ham (Genesis 10:6). The emphasis here is due to the common argument at that time Noah’s curse served as a justification for slavery and that Ham was the progenitor of the African people. For Crummell, according to Schipper, Noah’s curse has no effect on people of African descent.

Crummell links the curse of Canaan to the conquest of the land of Canaan by the Israelites entirely separate from any activity in Africa.

One should note in passing another view prevalent at the time. This was that God created lesser human beings before white Adam and Eve. This pre-Adam view adds another wrinkle to the story of how white people used the Bible.

BENJAMIN TUCKER TANNER AND THE BLESSING OF HAM

Tucker received his formal theological education at Western Theological Seminary before becoming a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1869, he published a pamphlet The Negro’s Origins and Is the Negro Cursed? also available online and which I downloaded.

Tucker’s arguments overlaps with those of Pennington and Crummell although he does not cite them. He adds that it must have been Canaan who originally offended Noah and not Ham. Sometimes biblical texts use the word “son” to mean “grandson.” This is an example of biblical exegesis in which scholars sometimes engage. He also notes that the biblical story never described what exactly was done to Noah, another void that biblical scholars seek to fill. He further wonders why Canaan did not follow his brothers into Africa. The question implies that Noah and his sons were in the Middle East, a reasonable assumption given the story of the Tower of Babel and therefore perhaps were white, a line of reasoning he does not pursue. Indeed, the Hamitic hypothesis in Egyptology posits just such a view. Neither Tanner nor Schipper address that view and some Egyptologists are loathe to even mention this part of their discipline today but that is a separate topic.

The problem Tanner addresses is that anti-Black interpreters insist that Ham is the guilty party and the one Noah curses because Ham is the one associated with Africa. Schipper reports that Tanner ends his pamphlet with the admonition that despite pro-slavery interpreters seeing what they want to see in the biblical text, Ham is not cursed, his descendants from Africa are free, and they still enjoy the blessing that God bestowed on all of Noah’s children.

GEORGE WASHINGTON WILLIAMS AND THE BLESSING OF HAM

Williams served in the Ohio state legislature after receiving his formal theological education at Newton Theological Institution, now Andover Newton Theological Seminary. In 1882, he published History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1881, another book available online. His opening chapter is “The Unity of Mankind.” Williams like Tanner regards the curse by the human Noah as a prophecy about what will happen to Canaan. He questions Noah’s prophetic abilities and claims from a biblical viewpoint the curse was never fulfilled, it was not the word of God. What we are dealing with “was only the bitter expression of a drunken and humiliated parent lacking divine authority.”

In his conclusion, Schipper observes that these nineteenth century scholars read the repopulation of Africa in the post-diluvian era detailed in the Table of nations in Genesis 10 as part of the glorious realization of God’s blessing in Genesis 9.

He also notes the formal theological education these four scholars received at Yale, Cambridge, Heidelberg, and Newton. They engaged with the scholarship of their time. They followed standard exegetical practices in American biblical scholarship as practiced at that time. They should be included in any discussion about the history of American biblical scholarship during that time period.