August 28, 2019, marked the seventh birthday of the failed Path through History project. I was there on August 28, 2012, with hundreds of others for the opening fanfare. People were excited about this new initiative to revitalize cultural heritage tourism in the state with the creation of paths through history. As reported in CityLab (Amanda Erickson, 9/12/12),

…the Path through History…aims to turn upstate New York’s past into a tourist draw….Eventually the program will encompass an interactive website and smartphone app that “allows tourists to custom-trailer a trip based on specific top areas.”

Little did anyone know that the resulting project would rapidly degenerate into a big yawn signifying nothing.

Even as I write this blog, history sites throughout the state are being asked to submit events to the Path website for the Columbus Day weekend. As always these events will be local attracting people from the surrounding communities just as they would if the Path project did not exist. It is unlikely that there will be any paths, routes, itineraries, or anything that involves collaboration and cooperation among sites to draw on the buzzwords from seven years ago.

In this blog, I wish to explore the challenge of creating a viable cultural heritage tourism route/road/path. I have chosen three recent examples which highlight some of the potential as well as obstacles to developing such programs. In general, such endeavors are beyond what an individual site alone could do. The three are the Dutch in the Hudson Valley, history signs in Vermont, and an African American trail in Massachusetts. None of them are actual cultural heritage tourist programs at present but all involve or are related to the task of creating one.

The Dutch in the Hudson Valley

This example comes from an article in the Sunday Travel section of the New York Times published June 23, 2019, by Russell Shorto. The article covered the front page and two pages in the middle of the section. If you are familiar with the Sunday paper then you know that is a lot of space. Shorto’s name also should be familiar as a writer and speaker about the Dutch presence in New York State.

On October 17, 2017, I participated in a program convened by Cordell Reaves, Historic Preservation Program Analyst, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation (NYSOPRHP). The title was “Connecting Dutch Heritage in the Hudson Valley Corridor.” People from a wide range of government and private organizations attended. Every “food group” in the history community was represented quite literally as we had Dutch food for lunch. Shorto was the plenary speaker.

During the one-day conference, we broke into roundtables to discuss a variety of subjects.

The Red Group: Research is the foundation on which all of our work is based- how do we get it out to the public

What new research or new programs are happening that could lead to potential programming collaboration?

The Blue Group: A freewheeling discussion followed focusing on the topic of educational/interpretive programs.

The Green Group: What problems exist that are keeping facilities from moving forward with their programming?

The notes from the discussions were subsequently typed up and circulated to the attendees. (I am using that PDF as the source document for this section). I am not aware of any followup to these discussions which does not necessarily mean there was not any.

Subsequently, Cordell sent notices about the logo and the website to be used for the submission of Dutch-related events. Periodically, I receive notices about individual events but such notifications tend to be from the individual group presenting the event.

In the end it was Shorto himself who created an actual Dutch in the Hudson Valley Heritage tour. He did this by driving one weekend to the Dutch sites in the Hudson Valley. He started with the van Cortlandt House in the Bronx and headed north. He crossed the Hudson River on the Mario M. Cuomo Bridge with a “twinge of sadness” for the demise of the previous name, the Tappan Zee Bridge, a name that lives on with everyone who is not a government employee. His journey took him to Historic Huguenot Street in New Paltz, the Stone House Bed & Breakfast in Hurley for the night, back across the Hudson to Kinderhook, Valatie, and Stuyvesant Falls, the Columbia Historical Society in the Lucas Van Alen House, the Mabee Farm with its barn, and the Van Ostrande-Radill House in Albany. It appears that he drove straight back to New York from there.

During his trip as a renowned author, Shorto had the opportunity to meet with people not normally on a tourist agenda. Similarly when I was doing Teacherhostels/Historyhostels we also met with people not normally available to the everyday tourist and for longer times than a standard tour. Still his weekend jaunt suggests the possibilities for a weekend tourist program and even a week long one with some more sites and extended tours of different sites. However, to the best of my knowledge no such tours exist although there have been some attempts to create one.

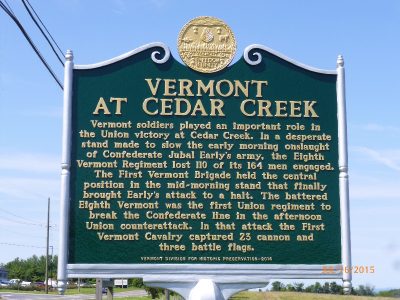

VERMONT ROADSIDE HISTORY MARKERS

The second item comes from a notice I received about a new web page for the roadside history markers in Vermont. I was impressed by the comprehensiveness of the state’s recordkeeping and the accessibility of information about the individual markers.

Unveiled in 1947 by the Vermont Legislature, the Roadside Historic Site Marker program has proven an effective way to commemorate Vermont’s many people, events, and places of regional, statewide, or national significance. Over 265 cast-aluminum green markers, crested with the distinctive gold state seal, are placed throughout Vermont to provide a fascinating glimpse into the past and insights into the present.

If you wish to report a missing or damaged marker, please email Jennifer Lavoie at jennifer.lavoie@vermont.gov. Please let us know the name of the marker, location, and when you first noticed it was missing or damaged.

For new roadside historic marker, please review the Vermont Roadside Historic Site Marker criteria for evaluation and marker application.

Applications for new State funded roadside historic site markers will be accepted after March 1, 2020.

To submit application forms, ask questions, or request additional information, please contact Laura Trieschmann at (802) 828-3222 or laura.trieschmann@vermont.gov.

The website also has a listing of the markers one can download and an interactive map showing their locations. Apparently, Vermont takes it history markers seriously. Wouldn’t it be nice if every state did?

And then there is the tourism factor. People sill stop and take a photograph at a history sign. People will search out such signs. Typically tourist departments do not think of history markers as tourist destination points. After all there may be no visitor center there, no staff, no bathroom, and limited or no parking. Yet the fact remains that people do want to stand at the exact spot where some event occurred or some person lived. For example, there are a slew of John André markers besides the one where he was finally captured in Tarrytown and then hanged across the river in Tappan. How will people know such signs exist unless they live there and drive by them all the time? What about tourists?

One area of neglect is the linking of state history marker database (assuming it exists) with the tourist data base. Do you even have a complete inventory of the history markers in your village, town, city, county, or state? How many of them need repair? How many of them have inaccurate information? How many additional signs are needed to include people and events frequently ignored in the traditional history narratives? Imagine if high school students next spring for their senior service project canvassed their municipality for the history makers present and needed. Imagine if state history departments compiled an up-to-date listing. Imagine if history markers were linked to the state tourist map. There is more to cultural heritage tourism than big places with bathrooms, food, and gift shops. History markers should be included in cultural heritage tourism itineraries.

AFRICAN AMERICAN TRAIL PROJECT

At the Massachusetts History Alliance Conference on June 24, 2019, professors Kendra Taira Field and Kerri Greenidge of Tufts University presented their African American Trail Project. They originated and completed the project inspired by another Tufts professor and with student assistance. It was not done at the behest of any tourist organization. At the conference, they distributed a map with 236 sites and there is a website with them as well…which is easier to update than the map.

The sites are not linked through any standard logo. Sites may not even have a sign of any kind. Sites may not even know they are on this trail. In this sense it is more of a database of identification than a working tourist itinerary.

Over the July 4 weekend, I was in the Berkshires and decided to visit the sites listed on the map for the region. I started with the Stockbridge Cemetery since I was familiar with it from the Stockbridge Indian conferences I had attended (see Stockbridge Indian Conferences: Remembering the Indian Nations in American History). However finding the individual grave marked on the map in the actual cemetery was a little like finding a needle in a haystack. I decided instead to stop at the Stockbridge Museum and Archives which is not on the map. There I spoke with curator Barbara Allen. She informed me about the African American related exhibits and information at the historical society that one should see prior to going to the cemetery.

She also informed me about the African American Heritage in the Upper Housatonic Valley Trail. I had written briefly about the Upper Housatonic Valley National Heritage Area after picking up a brochure at the Stockbridge Indians Conference. I did not know about all their trails at that time. There are a variety of them. In fact, there is a counterpart to the Hudson Valley Ramble in September with a slew of walks and events in Berkshire, MA, and Litchfield, CT, over the four weekends. These four weekends provide great opportunities to create weekend programs not just for African-related sites but for history sites in general. Instead they are a collection of random events.

Moving on from Stockbridge, I then went to the James VanDerZee birthplace in Lenox. By coincidence, I had just seen an exhibit of his photographs from the Harlem Renaissance at ArtsWestchester in White Plains. The home is no longer standing and there is no sign there. Due to a recent fatal car accident, a change was made on Route 7 by the site which changes access to it. However I did go to the Lenox Library and it had a folder of materials on him including a savings account statement.

There are several W. E. B. Du Bois sites on the trail. The Du Bois Center in Great Barrington is in a small strip mall and doubles as a book store. It is a fount of academic materials and is not open to the public unless by chance the proprietor happens to be there. The W.E.B. Du Bois Homesite offers two free guided tours on Saturdays and Sundays during the summer season with a Ph.D. candidate but the brochure I picked up is dated 2016. The current website lists three tours for all of 2019. At the Great Barrington Visitor Center, I was informed of the Housatonic River Walk which goes by 200 feet from where Du Bois was born. The Housatonic is the “golden river” Du Bois wrote about. There is a park and garden there in his honor. The Riverwalk is not on the African American Trail Project.

The African American Trail Project is a work in progress. It will expand as additional research is done. I mention my own adventures to highlight the challenges in creating such a trail and transforming it into a tourist itinerary. I do so based on my own experiences in creating Teacherhostels/Historyhostels. They were very time consuming to create. In addition to research via the web, emails, and phone calls, on-site visits are still required. Plus as one delves into the site and talks to the people, one never knows what additional locations or people will be mentioned. In short, and to bring this long post to a close, to create actual tourist itineraries beyond the superficial ones of crossing places off a bucket list takes time and effort. Those qualities are precisely the ones that have missing in the New York State Path through History and any other program that simply lists places and/or signs.