Negro and Indian are not slur words … unless you want them to be. Negro and Indian are not derogatory words … unless you want them to be. Negro and Indian are not terms of insult … unless you want them to be. We determine not only what words mean but their subjective value. Terminology matters Perhaps the most famous divergence is between the Civil War and the War of Northern Aggression.

The appearance of “Negro” and “Indian” can prove problematic for history organizations, historians, teachers, students, and talk show hosts and newscasters. They may not be able to say the word even when it appears on screen or in a powerpoint. But erasing these words distorts the historical record and undermines understanding why they were replaced. These words have not disappeared from the historical record and continue to be used today.

In other blogs, I have examined the use of the word Indian today. Now I shift to the word Negro.

In this blog, I am continuing my investigation into the demise of the Negro era in American history due to decisions made by white people in the 1930s-1960s and the birth of the African American era. In my previous blog on this subject (The Destruction of Negro Communities and the Birth of the African American (February 28, 2023), I presented two similar but different migrations: the Great Migration of Negroes from the South and the Ellis Island migrations from southern and eastern Europe. Back then around a century ago, Negroes, Italians, and Jews all were considered to be not white.

At first all three peoples were succeeding in living the American Dream. James Weldon Johnson, head of the NAACP in New York wrote in 1925:

In the make-up of New York, Harlem is not merely a Negro colony or community, it is a city within a city, the greatest Negro city in the world. It is not a slum or a fringe, it is located in the heart of Manhattan and occupies one of the most beautiful and healthful sections of the city. It is not a ‘quarter’ of dilapidated tenements, but is made up of new-law apartments and handsome dwellings, with well-paved and well-lighted streets. It has its own churches, social and civic centers, shops, theaters and other places of amusement. And it contains more Negroes to the square mile than any other spot on earth. A stranger who rides up magnificent Seventh Avenue on a bus or in an automobile must be struck with surprise at the transformation which takes place after he crosses One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street. Beginning there, the population suddenly darkens and he rides through twenty-five solid blocks where the passers- by, the shoppers, those sitting in restaurants, coming out of theaters, standing in doorways and looking out of windows are practically all Negroes; and then he emerges where the population as suddenly becomes white again. There is nothing just like it in any other city in the country, for there is no preparation for it; no change in the character of the houses and streets; no change, indeed, in the appearance of the people, except their color. (“Harlem, the Culture Capital,” in The New Negro: An Interpretation, Alain Locke, ed. 1925; see also “The Seligmans, Philip Payton & Harlem’s Black-Jewish Alliance” by James Kaplan in New York Almanack 4/10/23).

I used the metaphor of baseball to represent that success. Hank Greenberg of the Detroit Tigers and Sandy Koufax of the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers were Jews. Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers was Negro. Joe DiMaggio of the New York Yankees and Carl Furillo of the Brooklyn Dodgers were Italian. Roy Campanella, Negro mother and Italian father, was biracial with the Brooklyn Dodgers. The one obvious difference was that Robinson and Campanella had to play the Negro Leagues before reaching the major leagues.

As it turns out, Negroes did not simply disappear from history with the switch to African American in the late 1960s. Since that earlier blog, I have come across numerous examples of the continued presence of Negroes as demonstrated in the examples below. These examples do not derive from any research I did. I conducted no search on the web. They simply are examples of the ongoing presence of the Negro in American history evident from the newspapers, magazines, and journals I receive (hard copy) and the notifications and announcements I received to my email. I was surprised at the frequency of the mentions.

In roughly chronological order:

AMERICAN REVOLUTION

2026 and Black Americans: A Conversation about Benjamin Quarles author of The Negro in the American Revolution (Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture 6/28/23 online)

Four scholars gathered to discuss the long-term impact of Benjamin Quarles’s scholarship: Adam X. McNeil (Rutgers University), Rebecca Brannon (James Madison University), Derrick Spires (Cornell University), and Michael Dickinson (Virginia Commonwealth University). They shared stories about their first encounters with The Negro in the American Revolution, its role in shaping their own research and teaching, and the ways in which they see Quarles’s influence on the scholarship of the American Revolution overall.

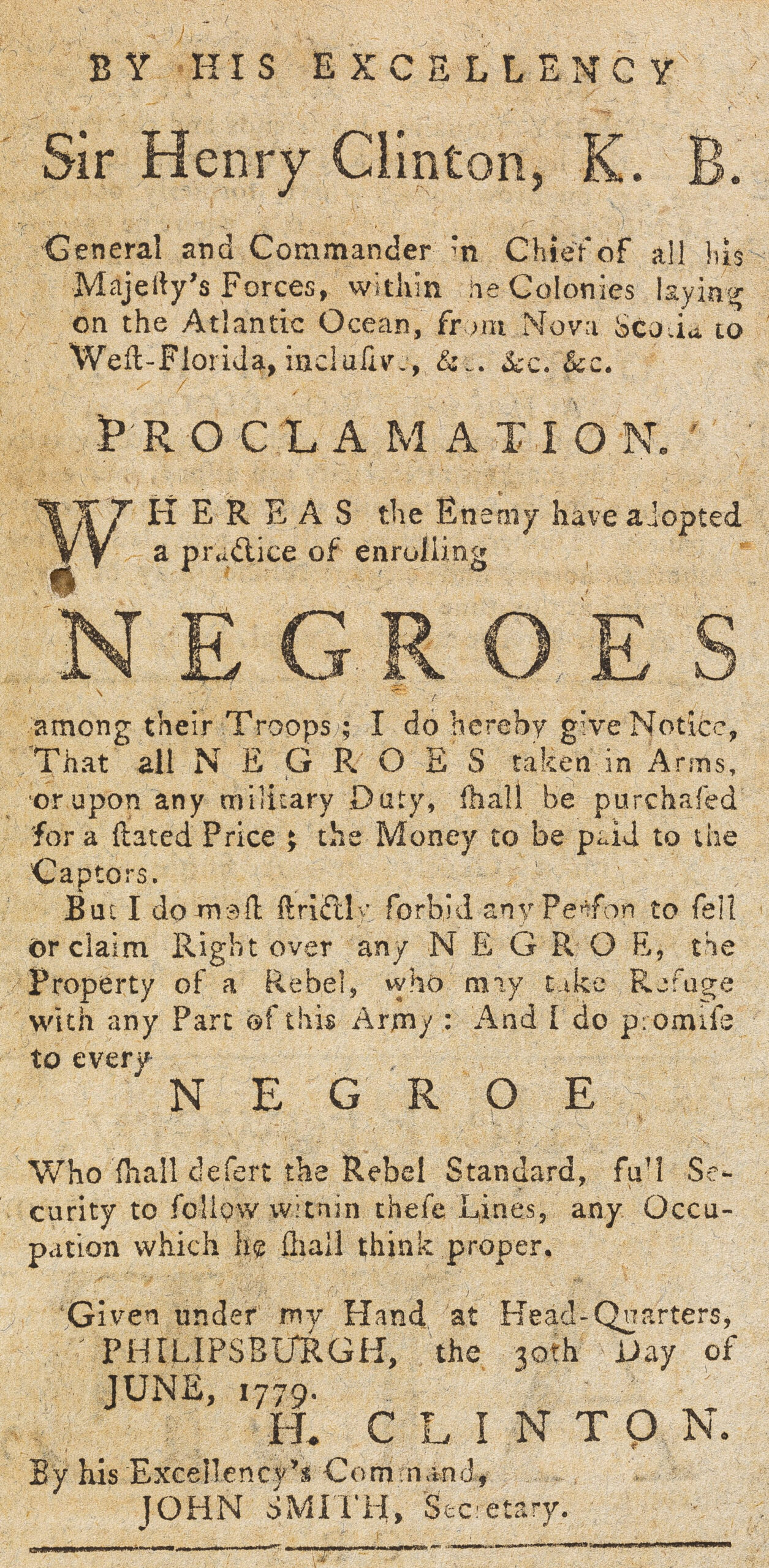

The Philipsburg Proclamation (Philipse Manor Hall, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation 6/30/23 online)

On this day, June 30, 1779, General Sir Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of His Majesty’s Forces in North America, issued the Philipsburg Proclamation at Philipse Manor. It would go on to have a huge impact on the American Revolution.

By His Excellency Sir Henry Clinton, K. B. General and Commander in Chief of all this Majesty’s Forces, within the Colonies laying on the Atlantic Ocean, from Nova Scotia to West-Florida, inclusive, &c., &c., &c.

PROCLAMATION.

Whereas the Enemy have adopted a practice of enrolling Negroes among their Troops; I do hereby give Notice, That all Negroes taken in Arms, or upon any military Duty, shall be purchased for a stated Price; the Money to be paid to the Captors.

But I do most strictly forbid any Person to sell or claim Right over any Negroe, the Property of a Rebel, who may take Refuge with any Part of this Army; and I do promise to every Negroe Who shall desert the Rebel Standard, full Security to follow within these Lines; any Occupation which he shall think proper.

Given under my Hand at Head-Quarters, Philipsburgh, the 30th Day of June, 1779. H. Clinton.

By his Excellency’s Command, John Smith, Secretary.

Carleton refused to break the promise of the Philipsburg Proclamation and those that came before it. He oversaw the evacuation of thousands of Black Loyalists, and it is through his efforts that the Book of Negroes was compiled and survives as one of the best primary sources on Black Loyalists in the period.

The Birch Trials (exhibition, Fraunces Tavern Museum, 6/26/23 in person)

I attended the preview of the opening of this exhibit. Obviously the Book of Negroes figures prominently in it.

ANTEBELLUM PERIOD

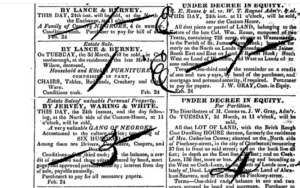

“How a Grad Student Uncovered the Largest Known Slave Auction in the U.S.” (ProPublica 6/16/23 online)

Lauren Davila made a stunning discovery as a graduate student at the College of Charleston: an ad for a slave auction larger than any historian had yet identified. The find yields a new understanding of the enormous harm of such a transaction.

On page 3, fifth column over, 10th advertisement down, she read:

“This day, the 24th instant, and the day following, at the North Side of the Custom-House, at 11 o’clock, will be sold, a very valuable GANG OF NEGROES, accustomed to the culture of rice; consisting of SIX HUNDRED.”

She stared at the number: 600.

A sale of 600 people would mark a grim new record — by far.

The article goes on to recount the effort to locate the owner of this gang of Negroes. In so doing it shed light on a part of the history of Charlestown previously unknown.

“Improper and Almost Rebellious Conduct”: Enslaved People’s Legal Politics and Abolition in the British Empire” (American Historical Review June 2023)

The current issue of the journal of the American Historical Association contains an article about events in Great Britain and its Caribbean colonies mainly in the 1820s and 1830s on the abolition of slavery. The article does mention Negroes multiple times in reference to texts from that time period.

Frederick Douglass

“I want a home here not only for the Negro, the mulatto and the Latin races; but I want the Asiatic to find a home here in the United States, and feel at home here, both for his sake and for ours. The outspread wings of the American Eagle are broad enough to shelter all who are likely to come” (NYT 7/2/23 print).

In this op-ed piece Jamelle Bouie quotes Frederick Douglas in Boston from 1867 as the 14th Amendment and birthright citizenship was being debated. It would seem that Douglass’s vision of a “composite nationality” as a beacon for all peoples resonates with the author today.

W. E. B. Du Bois

As part of the American Historical Association amends for racist practices, the history organization is conducting book reviews of books previously ignored. The December 2022 issue has a review of Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy, 1860-1880 (1935).

According to the reviewer,

Du Bois battled with editor J. Franklin Jameson over the punctuation of “Negro.” When Du Bois returned the initial proof, he asked that “Negro” be capitalized “as a matter of courtesy.”

In the exchange of letters with the editor, Du Bois wrote:

…”the word Negro is almost universally capitalized” in European countries and had been capitalized in the United States until about 1840, “when ‘Negroes became definitively cattle for all time.”

According to the reviewer,

… to capitalize “Negro” in the pages of AHR (American Historical Review) and to take seriously his larger interpretation, required an acceptance of the radical idea of Black personhood. [Du Bois wrote] “I am going to tell this story as Negroes were ordinary human beings…”

The reviewer continues to quote passages from the book where Du Bois used the term “Negro.” Can you imagine this debate taking place today?

The reviewer comments that “Perhaps better than any other work before or since, Black Reconstruction captures the tragedy of U.S. history.”

Du Bois appears in a second book review, this book not by him but about him: The Wounded World: W.E.B. Du Bois and the First World War (NYT 6/4/23 print). The reviewer cites this passage from the book spoken by Du Bois:

“I did not believe in war, but I thought that in a fight with America against militarism and for democracy we would be fighting for the emancipation of the Negro race.”

Such sentiment did not blind Du Bois to the reality “that American white officers fought more valiantly against Negroes within our ranks than they did against the Germans.”

BASEBALL

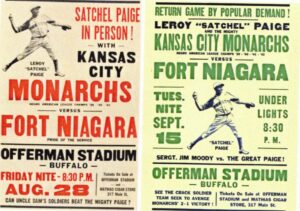

“Return of the Monarchy… i.e., The Kansas City Monarchs: Fort Niagara and Satchel Paige (Fortress Niagara newsletter June 2023 print)

The story of a visit by the Kansas City Monarchs, Negro American League Champion in 1939, 1940, 1941, and 1942, on August 28 and September 15, 1942 to Offerman Stadium in Buffalo to play the Fort Niagara military team stationed at the fort. The Monarchs won the first game and Fort Niagara won the second game with Paige pitching three scoreless innings in the second.

“Negro Leagues Baseball Museum announces plan to build new $25 million museum campus” (KSHB 5/2/23 online)

… the spirit of the Negro Leagues still is strong through the iconic Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

Now, the museum is about to get bigger, as the NLBM and president Bob Kendrick announced plans Tuesday to build a new $25-million campus for the museum Tuesday, the 103rd anniversary of the first Negro League game.

“The Double Life of Ernest Withers: A new documentary probes the achievements — and betrayals—of an iconic civil rights photojournalist” (The Pennsylvania Gazette May/June 2023 print). The article references his photographs of the celebrated Memphis Negro League baseball team.

“Reviving a Negro Leagues Monument: Saved from demolition with a $100 million makeover, Hincliffe Stadium reopens as a minor league park and museum” (NYT 5/18/23 print).

This banner headline tells the story of one of the last of the Negro leagues ballparks still standing. Though abandoned, this Patterson, New Jersey Field of Dreams has been brought back to life.

“Remembering when Baseball Was His Calling: The Rev. William H. Greason, 98, aided Willie Mays and was in the last Negro World Series” (NYT 6/5/23/print)

This huge three-page article about the oldest living Negro leagues player obviously abounds in the use of the term “Negro.” It also refers to the Southern Negro League Museum in Birmingham, Alabama.

“In Homage to Mays and the Negro Leagues, M.L.B. Heads to Birmingham” (NYT 6/21/23 print)

Rickwood Field, believed to be the oldest professional baseball stadium in the United States, will host a Major League game on June 20, 2024. This action is part of the celebration by the M.L.B. of Negro League baseball. One hopes that Willie Mays, age 92 and born five miles away, and William Greason, age 98 (above) will witness this stadium where they once played.

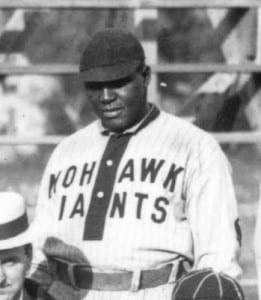

“Schenectady Baseball History: The Mohawk Giants” (6/29/23, New York Almanack, online)

One highlight was in 1939:

During this season the team was also invited to partake in Baseball’s Centennial Program in Cooperstown where Negro baseball was given recognition. The Giants would play the New York Cubans of the Negro National League and lose 6-0.

“The Negro Leagues are major leagues — but merging their stats has been anything but seamless” (theathletic.com 5/11/23 online)

DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL CONVENTION

In a major op-ed piece about the machinations in the Democratic presidential convention of 1948, Samuel Freedman quotes (NYT 7/19/23 print) A. Phillip Randolph, a labor and civil rights leader, informing Harry Truman in the White House:

“The Negroes are in the mood not to bear arms for the country unless Jim Crow in the armed forces is abolished.”

EDUCATION SEGREGATION: BROWN AND NOW

In an op-ed piece also following the recent Supreme Court

decision on affirmative action (NYT 6/30/23 print), Jerome Karabel quotes Thurgood Marshall:

“It is more than a little ironic that after several hundred years of class-based discrimination against Negroes, the court is unwilling to hold that a class-based remedy for that discrimination is permissible.”

On the same topic a few weeks later, Richard D. Kahlenberg wrote an op-ed piece “Focus on Class, Not Race: Affirmative action still exists — for the rich (NYT 7/9/23 print) He references first Whitney Young of the Urban League who had called for “a decade of discrimination in favor of Negro youth.” He then quotes Martin Luther King:

“It is impossible to create a formula for the future which does not take into account that our society has been doing something special against the Negro for hundreds of years”

OBITUARIES

The death of Jim Brown in May led to numerous tributes and length obituaries about the Hall of Fame football player. He is still cited as a person who left on top of his career instead of fading into retirement as a much lesser player. When playing for the Cleveland Brown, he founded the Negro Industrial and Economic Union. He is quoted as having said in 1968 about his film career:

“I don’t want to play Negro parts. Just cool, tough modern men who are also Negroes. And not good guys all the time” (NYT 5/20/23 print).

The death of C.R. Roberts, 87, Unstoppable Rusher in Breakthrough Against Segregation (NYT 7/19/23 print) reported on a less well-known figure. “…[O]ne local newspaper in 1954 extolled him as the “all-American Negro flash.” Two years later he ran for 251 yards against an all-white Texas team. The obituary includes mention of the famed games of Texas Western against Kentucky for the NCAA basketball championship in 1966 and USC against Alabama in 1970. The latter two games were eye-openers for famed white coaches Adolph Rupp and Bear Bryant.

THE NAME GAME: URUGUAY

In an article “Uruguay Has a Beef, and It’s Not With China” (NYT 7/20/23 print), there is a reference to sturgeon being raised in the “River Negro.” Apparently Uruguay is not Texas where place names with the word “Negro” are being removed. There is no indication about whether or not Uruguay got the memo.

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

[In the review of Requiem for the Massacre: A Black History on the Conflict, Hope and Fallout of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre by RJ Young (NYT 1/1/23 print), the reviewer cites Young’s search for the phrase “Black Wall Street” falsely attributed to Booker T. Washington. The reviewer cites Young’s disdain for the ubiquitous use now of the historically inaccurate term even as part of the history center’s official name.]

The review of the King book concludes with:

Here was man building a reform movement on the most American of pillars: the Bible, the Declaration of Independence, the American dream.

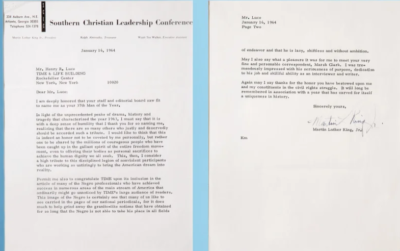

In a Jan. 16, 1964, letter to TIME co-founder Henry Luce, King explained what that designation of Time’s Man of the Year meant to him—and to the movement:

In light of the unprecedented peaks of drama, history and tragedy that characterized the year 1963, I must say that it is with a deep sense of humility that I thank you for so naming me, realizing that there are so many others who justly and deservedly should be accorded such a tribute. I would like to think that this is indeed an honor not to be coveted by me personally, but rather one to be shared by the millions of courageous people who have been caught up in the gallant spirit of the entire freedom movement, even to offering their bodies as personal sacrifices to achieve the human dignity we all seek. This, then, I consider a high tribute to this disciplined legion of nonviolent participants who are working so untiringly to bring the American dream into reality.

Permit me also to congratulate TIME upon its inclusion in the article of many of the Negro professionals who have achieved success in numerous areas of the main stream of America that ordinarily might go unnoticed by TIME’s large audience of readers. This image of the Negro is certainly one that many of us like to see carried in the pages of our national periodicals, for it does much to help grind away the granite-like notions that have obtained for so long that the Negro is not able to take his place in all fields of endeavor and that he is lazy, shiftless and without ambition.

Martin Luther King, Jr. (published 2/28/23 print)

Look at what is missed by erasing the Negro from American history. Negroes wanted to and were living the American dream. In “Growing Injustice, Growing Dissent” (NYT 6/4/23 print), the author writes:

Being Armenian, my family was barred from living on the fancy side town for a half-century. No Negroes, Asians, Armenians or Mexicans, the deeds read.

Asians are still here.

Armenians are still here.

Mexicans are still here.

What happened to the Negroes?