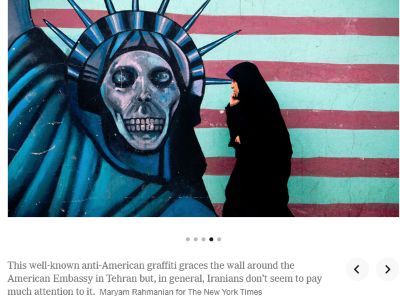

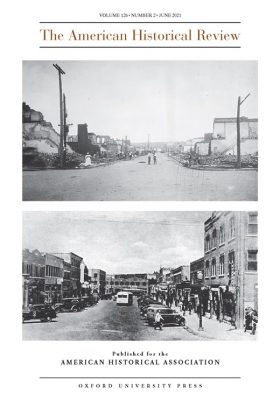

Should historians leave the ivory tower and become social advocates? The question was raised in the current issue of American Historical Review (AHR) in an article by Karlos K. Hill entitled “Community-Engaged History: A Reflection on the 100th Anniversary of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.” Much of the article chronicles the author’s own participation in the commission for that anniversary. Those actions are not the subject of this post. Instead, his comments about the role of the historian are.

HISTORIANS AS SOCIAL ADVOCATES

The first part of the article describes the actions of one hundred years ago and some afterwards. Part II of the article begins with:

THERE IS A GREAT DEAL OF DISAGREEMENT about how historians should best engage with their communities and with the communities impacted by the histories they study.

Hill then refers to an earlier exchange in AHR on “Historians and Native American and Indigenous Studies.” That exchange was the subject of two previous blogs here Native American and Indigenous Studies: Another Culture Wars Episode and Violence and Native American and Indigenous Studies (NAIS). Hills takes issue with historian David Silverman’s criticisms of the other scholars in this exchange and adds:

…his anxiety over what is rigorous, objective history gets to the heart of what I have been mulling. I suggest that as historians we can do legitimate scholarship that advances the field while simultaneously engaging our communities in ways that confront and address the present-day legacies of anti-Black violence and racial injustice. Working on the history of the Tulsa massacre has shown me that community-engaged history is not methodologically dubious; it is substantive and effectual.

Fair enough. Historians disagree on the value of a certain investigative approach and of the potential dangers of bringing personal agendas into community-engaged history particularly if the scholar is a member of the community. However Hill overlooks the consequences if that approach is applied in other communities such as a Confederate one.

Hill then adds a new wrinkle to the debate:

I write this as a scholar whose identity has evolved to be in service to the community. A few years ago, I had reached a point where conferences and papers and books were not enough to keep my passion alive. I found myself asking, How does scholarship live in the world, connected to real-world issues for my community that are complex and unique?

As I read this, Hill is stating that a scholar should do exactly what Silverman criticized scholars for doing.

But each historian has different subject expertise, a different skill set, and different passions, and therefore being a catalyst for progressive, inclusive social change will differ for each of us, depending on where we are situated.

Again, as I read Hill, he presupposes that historians should be advocates for progressive inclusive change. The only difference is that different historians will advocate for different communities based on their different expertise and passions. The concept of “ivory tower” scholarship or “objective” scholarship has been cast aside.

Hill arrived at this point based on his own personal experiences.

I am tired. I am burned out because of the realities of being a Black man in America and being a Black scholar in academia in Oklahoma. I am burned out because the American history I study is violent and difficult even though it is so important…. And yet here I am. I persist in doing work as a historian that I think is essential for healing and change.

Hill is quite open about his definition of a historian: the historian should be a catalyst for progressive and inclusive social change to heal the historian’s community.

He declares that:

we (historians) possess tremendous power to promote social justice in ways that align with community goals, healing, and identity making.

He is especially concerned with what is taught is schools and what is taught to the teachers who teach in those schools. In Section III, Hill observes that in Oklahoma, while Tulsa now is included in the social studies standards, “there has been no statewide effort to create a curriculum to teaching it.” The rest of the section includes his recounting of his teacher-training workshops to address that shortcoming. He concludes with:

What is it that people are really asking? The answer that I am sitting with and mulling right now is this: Accurate, engaging history of racial violence that is rooted in the real needs of community members who are still feeling the tremors of the horror triggers people to imagine a future that they never had thought possible before. And in enabling that kind of reimagining, it also enables self-actualization.

Add “self- actualization” of the community to the job description of historians.

In the final section, Hill reflects on the lessons the learned from his experience with the commission. One methodological lesson was in the value and difficulty of teamwork. It is difficult because “Not many of us learned in our PhD programs how to conduct collaborative research.” Here is a specific change recommendation. I wonder if there is a difference in the training of public historians than for academic historians. Public historians are not trained to be “ivory-tower” historians and have more experience working the communities their museums and history organizations serve than do academic historians.

Hill observes that his “work with the Centennial Commission has reaffirmed for me the tremendous power historians have to effect societal change.” His final thoughts express the path he believes historians should take:

Social change occurs because I know they care, and I believe they will live in the world differently because of the community we have built. In my view, this is what historians can do to help bring about social justice. Our most important credential in building relationships with the community is not our expert knowledge but our desire to serve.

Historians should serve the community.

Hill shows himself to be a strong proponent of mandates provided they are the right ones. After all, suppose the views of anther community are diametrically opposed to the progressive inclusive social change advocated by Hill? Doesn’t that community have the same right for historians to serve them? Then it becomes a battle to the death in local school board elections everywhere or at the state level such as in Virginia.

“BAD MANDATES”

What makes a mandate good or bad is in the eye of the beholder. In the current issue of Perspectives on History” by the American Historical Association (AHA) [Yes, I am a member and receive print copies of these two publications], James Grossman and Beth English, the executive directors of the AHA and the Organization of American Historians (OAH) respectively co-authored an article on combatting misinformation. Their concern was that “The Integrity of History Education Is at Stake.”

They reported that AHA and OAH were part of a coalition of over 25 organizations called “Learn from History.” The goal of the coalition is to

combat deliberate misinformation about the current state of history education and the ways that historians write about and teach the centrality of racism to the evolution of American institutions.

This coalition was not the first foray of AHA and OAH into the political arena. Previously they had joined 147 organizations

…to condemn legislation that was introduced or enacted in 27 state legislatures with the aim of discouraging or prohibiting the straightforward coverage of topics in which issues of racism, sexism, and other “divisive” concepts arise.

The coalition expressed concern for teachers who face retribution for daring to defy such mandates. They “oppose cynical, politically motivated attempts to misrepresent what is taught in history classrooms…”

Welcome to the political arena. These history organizations are now officially part of the culture wars as warriors against the Trumpicans. There are consequences to that political stand.

THE PUBLIC’S VIEW ON HISTORY

To complete this trifecta of AHA publications, I turn to “A Snapshot of the Public’s Views on History” from the website. Here is a snapshot of the lessons learned from the survey.

First, our respondents had consistent views on what history is—and those views often ran counter to those of practicing historians. Whereas the latter group usually sees the field as one offering explanations about the past, two-thirds of our survey takers considered history to be little more than an assemblage of names, dates, and events…. In sum, poll results show that, in the minds of our nation’s population, raw facts cast a very long shadow over the field of history and any dynamism therein.

Social change, actualization, progressive inclusion were not attributes associated with historians. Hill would agree hence his call for a change in historians.

We also learned that the places the public turned to most often for information about the past were not necessarily the sources it deemed most trustworthy.

The top three sources involved films and TV in some manner. College courses and history lectures ranked towards the bottom. Visits to historic sites and museums were in the middle. Fortunately for the history profession, when it came to the trustworthiness of the various venues, the results were reversed. Museums and history organizations were held in high regard and films and TV not so much. One caveat I would add, is that people nationwide can see the same movies and TV shows and remember them while visitations tend to be local and smaller scale. I venture to say people know more about Spartacus from Hollywood than history.

As historians become political advocates for their community and take a stand in the cultural wars, the inevitable consequence is to jeopardize that aura of trustworthiness.

Another key point from my perspective is the correlation between what people think history is and the way history is taught. History is not simply an assemblage of names, dates, and events but if that is the way it is taught then that is how it will be defined by students who become adult voters.

So what are the lessons to be learned from this perusal of recent publications by the American Historical Association?

1. Historians are warriors in culture wars.

2. Historians accept the concept of legislated mandates provided they are the right ones.

3. In a community-based history approach, historians have the right to serve both Confederate and Union communities.

4. Every school board election is or will be a battlefield.

5 .To change the meaning of history to the public requires changing the way it is taught as a series of facts (dates, names, places).

The national narrative has unraveled. It will continue to do so as we approach July 4, 2026. And the country will unravel as well as separate communities teach separate truths and no one develops a national narrative for the 21st century.