“You never saw such a people in your life. Their manners and action are wild in the extreme. They are in a perfect state of nature and would be a curiosity to any civilized man.”

“At that time the Indians did not have anything but small farms, and of course the freedmen were reared among them, so they didn’t work like they should but just raised enough corn to make their bread.”

“The Negro is more like the white man than the Indian in his tastes and tendencies and disposition to accept civilization. The Indian rejects our civilization. It is not so with the Negro. He loves you and remains with you, under all circumstances, in slavery and in freedom.”

“The peopling of the national domain with an enterprising, intelligent and hardy race of emigrants—transforming the savage wilderness into flourishing civilized communities, multiplying new States, and adding immensely to the wealth and productive industry of the Nation…[would] extend the area of Freedom [and] would increase the power of the North and West—the power of the people—would menacingly the perpetuity of the institution of slavery and the Democratic slaveholding aristocracy built upon it.”

What do you make of these four quotations? How judgmental are you? Should the people who wrote these words be cancelled? Should they be taught in our schools? What do you do if actual history does not comport with your preferred way of understanding the past?

The first quotation comes future Choctaw Nation chief Peter Pitchlynn in 1828 about his visit to Indian Territory, now eastern Oklahoma. He was scouting the lands the Five Tribes or Civilized People, Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole Indians, would be relocated to in what became known as the Trail of Tears. When he encountered the people already living there he reacted in accordance with the Myth of the Empty Land (The Myth of the Empty Land: Creating a National Narrative). As a civilized person, meaning one used to a settled life of agriculture and writing, Pitchlynn saw wild people who to all intents and purposes were savages. This meeting of Plains Indians and the Choctaw may not conform to expectations but it really happened in history: when the Indigenous People of the southeast encountered the Indigenous people of Indian Territory they saw uncivilized wild people living in a perfect state of nature who would be a curiosity to any civilized person (as in suitable for museum display). Such encounters are typical of the human experience when an agricultural society (Neolithic) and a nomadic society (Paleolithic) society meet. The latter are always considered savage by the former.

The second quotation comes from Blain Holman, Chickasaw freedman who had lived among the Choctaw. He was referring to events following the Treaty of 1866. In that treaty, the victorious Union obligated the independent Five Tribes to emancipate their slaves and later to provide individual allotments of 40 acres to them. The Union forced this action on the Indian Nation, a foreign country or dependent nation per the Supreme Court. Such an action may be considered unjust regardless of what you think of the terms. The Cherokee had emancipated its slaves in 1863 but we will never know what the other Tribes would have done on their own without the Union intervention. Based on traditional Myth of the Empty Land, Indians did not own land the way Europeans and Americans did so it was permissible to take it and allot it to individuals. Holman was disparaging the lack of productive use of the allotted land.

The third quotation comes from Frederick Douglass. He opined what could be considered a white view towards the Indian. He was attempt to secure a more privileged position for the Negro in the social hierarchy in this ranking of the different peoples.

The fourth quotation also is from Frederick Douglass. Here he expands on the previous sentiments. It is an expression of progress.

Meantime a changed circumstance had occurred in Indian Territory. With the allotment of individual parcels to the freed Africans, the area began to draw similar people from elsewhere in the country. During the 1880s and 1890s, the word spread about the success of the Indian Freed People as the wealthiest Negroes in the United States. One result was the creation of black towns. Many of the founders of these black towns and the editors of its newspapers expressed similar views to those espoused by Douglass. The city of Tulsa grew out of these developments until it became the wealthy Wall Street of the Indian Freedmen and African migrants from elsewhere in America. The centennial of its destruction is only days away.

Combined, these four quotations expose the complexity of history. One oppressed people can oppress another people. One victim of settler colonialism can practice the very same on another people when given the opportunity to do so. History can be problematical. Are we ready to wrestle with troubling truths?

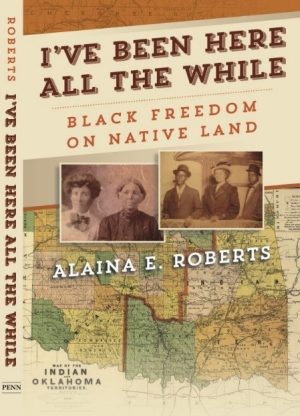

So asked Alaina Roberts, author of I’ve Been Here All the While, at the conclusion of her online presentation on May 6, 2021, for the American Philosophical Society. Only because of the changes wrought by the COVID-19 crisis was I able to see this talk. The four quotations, historical information, and terms come from her talk.

Roberts herself is a self-acknowledged mixed Indian-African person and her African family was owned by Chickasaw and Choctaw. The Indian Removal Act is a foundation story for the Five Tribes. Frequently overlooked are the African slaves who also made the journey. Another overlooked event was the effect these Five Tribes had on the native Plains People. They were dispossessed when the newcomers from the southeast arrived and the newcomers now became the new native peoples. As noted, Roberts drew attention to the Union imposing its will on the independent Indian Nations. For Roberts, the question she asks about wrestling with these troubling truths is both an academic challenge and a personal one her given her ancestry.

While the Freedman are Americans, are they also citizens of the Five Civilized Tribes? The answer for the Cherokee Nation is “yes” but only as of 2017 after much legal action. For the other four Indian Nations, the Freedmen are not recognized on full citizens. Sometimes the impact is practical. Certain Federal programs such as in housing or vaccinations only apply to members of the individual Indian nations. Sometimes the issue involves rights and heritage – the now Freedman have been part of the history of the Five Civilized Indian Nations for two centuries. Their histories are intertwined geographically, biologically, and culturally but not always legally or politically. The struggle is ongoing.

One must add to the conclusion of Hamilton the musical of “who will tell the story” what story will you tell? Roberts interview with CNN concluded with the comment:

“It has made me realize that this is still an issue, and that we need to talk about racism and prejudice as it is in all of our communities, and not just the White community.”