As with “The Three Faces of Eve,” Mount Rushmore has multiple personalities. It is like a Rorschach which tells different stories to different people according to John Taliaferro, author of “Great White Fathers: The True Story of Gutzon Borglum and His Obsessive Quest to Create the Mt. Rushmore National Monument.” It’s not exactly a palimpsest with hidden physical layers. It’s not exactly the story of the blind people and the elephant where no one can see the whole. But in way it is all of the above. It has multiple meanings simultaneously but one has to make the effort to see and understand them.

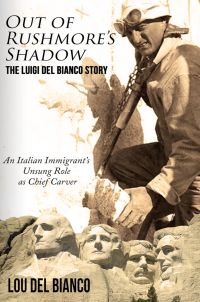

LUIGI DEL BIANCO

Probably the least familiar face of Mount Rushmore is that of Luigi Del Bianco, the chief carver of Mount Rushmore. His contribution to the creation of Mount Rushmore was long overlooked by the National Park Service (NPS). The Del Bianco family waged a tireless and ceaseless quest to have the family patriarch recognized in what at times must have seemed like a hopeless task. At last, the effort proved successful and Luigi Del Bianco now is officially recognized.

I became aware of this little known contributor to the carving because by chance I live in same village as he did, Port Chester, NY. In fact, it is the same village as his grandson Lou Del Bianco, the author of the book about his grandfather, lives. The grandson also was the driving force behind the creation of a village statue in his honor. I was there at the dedication.

Lou does reenactments of his grandfather. One fact that sticks in my mind, is how difficult it was for Luigi to get Italian food in South Dakota back in the 1930s! One should stop and pause for a moment and consider what it meant to this Italian immigrant to be working on this monument to America’s greatest presidents. He was doing so in the time of Joe DiMaggio, Frank Sinatra, and Columbus Day becoming a national holiday. In a different way, this story of Italian pride in being part of the American story is being repeated now in the journey of another people with the recent actions on Juneteenth, statues, monuments, and memorials to Middle Passage Africans, and the inclusion of their history as American history.

GUTZON BORGLUM

According to Stetson Kastengren, PhD student at the University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign and member of the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe, (Trump’s Mount Rushmore speech showed why our battle over history is so fraught, Washington Post, July 5, 2020), historian Doane Robinson, who had written on South Dakota history, came up with the idea for the monument in 1923. Robinson envisioned a memorial directing tourism to a Midwestern state. He wrote to U.S. Sen. Peter Norbeck of South Dakota that the handiwork of one sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, would “‘sell’ the Black Hills and [Custer State] Park as nothing else could.”

He [Borglum] explained to an audience in Rapid City, S.D., in 1925 that the monument would honor the “empire builders” by celebrating the “founder” and “savior” of America — George Washington and Abraham Lincoln respectively — and Thomas Jefferson, “the first great expansionist” who had secured the Louisiana Purchase. The fourth president who would be featured, Borglum’s friend Roosevelt, had “thrust himself upon the western plains” as a grieving younger man mourning the deaths of his wife and mother, and had expanded the American empire via the Panama Canal. The sculptor proclaimed, “If you carve … these empire-builders the whole world will speak of South Dakota.”

Borglum brought his own baggage to the creation of Mount Rushmore. His connections with the Confederate monument in Georgia’s Stone Mountain and the Ku Klux Klan make his role in the creation of the national monument problematic. So whereas Del Bianco was overlooked in the NPS telling of the story, Borglum’s biography was minimized to ignore the more distasteful elements of his life. But here is where the NPS is missing an exceptional opportunity to tell the story of America. Just as the Italian immigrant celebrating the history of his new country is part of the Rushmore story, so too are the Confederates who sought to destroy that country and the KKK which sought to destroy the ideals of that country. Here is where the NPS could make the visit to Mount Rushmore much more than a drive by tour with photo-ops and a tourist shop. It could tell the full story of the Mount which would be much more compelling.

THE FOUR PRESIDENTS

The four Presidents are the most familiar part of the Mount Rushmore experience. Even people who have never been there are likely to have seen the image at some point. Yes, it is a heroic portrayal of these four white men and the country they led. The “shrine to democracy” expresses leadership during four phases of American development: birth of the nation, westward expansion, preservation of the Union and emancipation, and industrial revolution. This is the traditional story, one which the NPS is skilled at telling.

Naturally today, there is a Woke version about these four men as well. I addressed that in a previous blog (Woke American Exceptionalism Is Still American Exceptionalism, July 23, 2020).

SIOUX LAND

To the Lakota, Cheyenne, Omaha, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Kiowa-Apache, the land is sacred.

The Great Sioux Nation consider the Black Hills a place of refuge that provides food, water, shade and sites to perform sacred rites. The hills belonged to the Sioux under the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty that stated the territory consisting of what is today western South Dakota was “set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation” of the Sioux Nation. (Kastengren)

IN the last few decades there has been various machinations in Congress and by the Sioux over land and money without there being much change.

As a result, some people want to turn the clock back and restore the land to the time before white people.

“Mount Rushmore is a symbol of white supremacy, of structural racism, that’s still alive and well in society today. It’s an injustice to actively steal Indigenous people’s land, then carve the white faces of the conquerors who committed genocide,” said Nick Tilsen, Oglala Lakota, who wants to see the monument removed and the Black Hills returned to the Lakota.

Julian Bear Runner, the president of the Oglála Sioux, said that Mount Rushmore should be removed in response to the recent controversy.

Unless the Sioux hire ISIS and/or the Taliban, this is not likely to happen. There needs to be a more constructive resolution in the real world.

MOUNT TRUMPMORE

According to South Dakota Republican Governor and non-Vice-Presidential candidate in 2020 Kristi Noem, she was told straight-faced in 2018 by the current President that his dream was to become the fifth face (“Mount Trumpmore? It’s the president’s ‘dream,’ Rep. Kristi Noem says,” Sioux Falls Argus Leader, April 24, 2018).

“I shook his hand, and I said, ‘Mr. President, you should come to South Dakota sometime. We have Mount Rushmore.’ And he goes, ‘Do you know it’s my dream to have my face on Mount Rushmore?’. “I started laughing. He wasn’t laughing, so he was totally serious.”

Apparently she even gave him a miniature Rushmore with a fifth face on it! There is a certainly irony in this dream or nightmare. He actually had the opportunity to be a Mount Rushmore caliber president (Mount Rushmore Opportunity for a Little Little Boy: Does He Know It? June 5 2020). When one considers the coronavirus, economic collapse, George Floyd, and China, he has had abundant chances to display leadership on a heroic scale. If he had the mental necessities, cognitive skills, courage, and strength of character to rise to the occasion, he would qualify as a Mount Rushmore quality president. But how can a child in the body of an adult with the emotional maturity of a three-year old (per Mary Trump) ever be worthy of a 60 foot carving?

MOUNT RUSHMORE: AMERICAN CIVICS TEACHING OPPORTUNITY

In the current issue of World Wildlife Magazine, Cindy and Harry Eisenberg, members of the WWF Northern Great Plains Advisory Committee, were asked about their interest in protecting the Northern Great Plains. Cindy responded:

“We fell in love with South Dakota when we visited Mount Rushmore.”

Harry spoke about a ceremony with local tribal leaders in 2005 when 16 bison were released on the plains of northern Montana, the first bison on the land in over a century.

The Northern Great Plains Indians were the subject of two blogs on the cancelled conference this year of the Organization of American Historians:

The Organization of American Historians (OAH) Conference: What Would Have Been Presented? April 22, 2020

Organization of American Historians Conference: II April 26, 2020.

There is both conservation and academic interest in land to say nothing of the event at Little Bighorn.

In short, there is a lot of American history connected to this site. That one mount with the four faces has ties to multiple facets of the story of who we are as a people as well as who we want to be as our journey continues. For the NPS, there is the challenge to go beyond the traditional to embrace all aspects of this one site. A land can be sacred to more than more people and for more than one reason. The reality is, for Americans, the land belongs to all us including Sioux, Italians, Presidents, conservationists, scholars and a host of others. The practical question for us a people is whether we are ready to tell that story in the fullest to build a better tomorrow or if we are to remain trapped in past.