On April 10, 2019, Politico posted an article entitled “Trump’s ‘truly bizarre’ visit to Mt. Vernon.” The article recounted a visit on April 23, 2018, by the French and American Presidents to Mount Vernon, home of George Washington, the first President of the United States.

According to Mount Vernon president and CEO Doug Bradburn, the tour guide for the Presidents, the Macrons were far more knowledgeable about the history of the property than the American President. France, of course, contributed to America’s victory in the American Revolution with the assistance of Marquis de Lafayette and Count Rochambeau, the first but not the last time foreign intervention helped elect an American President.

By contrast, the American President is renowned for not reading a book and being historically ignorant (Canada burned the White House, the Baltic States were responsible for the dissolution of Yugoslavia, and 306 electoral votes is a landslide). It was easy for the trained guide to rapidly discern that the American President was completely bored. Drawing on his experience with school visitors who similarly had no interest in the Father of the Country, Bradburn attempted to engage the person before him. As reported by Politico, the former history professor with a Ph.D, “was desperately trying to get [Trump] interested in” Washington’s house. So he drew on his bag of tricks and informed the uninformed President that Washington had been a real-estate developer.

That approach did the trick. Now the guide had the President’s attention. Not only was Washington a real-estate developer, but for his times, he was one of the richest people in the United States. In today’s terms, he could be compared to Gates, Buffet, and Bezos and not to a comparative pauper like the President. (No, Bradburn did not say that!) Again according to Politico, “That is what Trump was really the most excited about” said a source.

At that point, our narcissistic President responded to the news in the way that defines him as a person

[H]e couldn’t understand why America’s first president didn’t name his historic Virginia compound or any of the other property he acquired after himself. “If he was smart, he would’ve put his name on it,” Trump said, according to three sources briefed on the exchange. “You’ve got to put your name on stuff or no one remembers you.”

In other words, unless you make your name great, you are not great and will be forgotten.

The concept of making your name great is familiar to biblical students referring to another book he has not read.

Genesis 12:1 Now Yahweh said to Abram, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. 2 And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing.

In the biblical tradition, a person does not make his name great, the Lord does.

It should be noted that in ancient times the people who made their name great were kings. Lost in translation is the recognition that the way one made one’s name great in ancient times was by the king building something. To the deep regret of biblical archaeologists, ancient Israel did not partake of this royal tradition of kings building things with their name on it.

By contrast, Ramses II, the traditional Pharaoh of the Exodus of Passover fame, did make his name great. He built extensively. And when he had not built it, he still carved his name into it. It would be a little like our having the Trumpire State Building or Mount Vertrump. And Ramses did achieve lasting fame. By having approximately 100 children, a condom was named after him so his name is remembered all the time.

Mesopotamian kings followed a generally similarly path. Kings built stairways to heaven (ziggurats) at the cosmic center (the capital) where they ruled the universe from sea to shining sea (the Upper Sea or Mediterranean to the Lower Sea or Persian/Arab Gulf; there maps are oriented at a 90 degree rotation from ours). The baked bricks used in these constructions bore the name of the king.

Nimrod is the first king mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. He is the first king mentioned before Abraham encounters various kings. To understand what he is doing there one must put aside what the name means colloquially today and in rabbinic tradition and focus on the biblical text itself. In the original version of the story:

Genesis 10:8 Cush became the father of Nimrod; he was the first on earth to be a mighty man. 9 He was a mighty hunter before Yahweh; therefore it is said, “Like Nimrod a mighty hunter before Yahweh.” 10 The beginning of his kingdom was Babel, Erech, and Accad, and Calneh [Calah] in the land of Shinar.

These verses are descriptive, not accusatory. Nimrod is to be praised for his achievements not condemned. Indeed, he is a figure to be emulated given his success as mighty man or warrior before the Lord. He was the ruler of the Mesopotamian universe.

As biblical archaeologists and Assyriologists eventually learned, Nimrod was not an individual but an exemplar. He was not Sumerian Gilgamesh of Uruk (Erech) as had been originally thought. He was not Akkadian Sargon the Great of Accad, he was not Amorite Hammurabi of Babylon, and he was not Assyrian Tukulti-Ninurta of Calah to name other candidates. Instead he was all of them; he represented that Mesopotamian way of life.

To understand the Nimrod story, it is necessary, I think, to connect this story of the four cities with the inserts of the four rivers in the garden (Gen, 2) and the four kings of the east (Gen.14). A single author supplemented an existing narrative with these episodes. This author thought globally as he also did in transforming local flood songs (Songs of Miriam and Deborah) into a global one. That action undermined the Egyptian-based perspective of the Exodus story and the Canaanites who became Israelites. Having Nimrod be a Yahweh-worshipper long before Moses at the burning bush also undermined the position of Moses and therefore of his priesthood.

I suggest that the author the Nimrod story and these supplements was a Benjaminite/Yaminite Aaronid priest. He wrote not as a scribe or priest but as a player in the political arena. He ended the first cycle of stories (aka the primeval cycle) with Nimrod and a table of nations leading to Abram leaving Ur to start the second cycle. The torch had been passed to a new location. The temple in Jerusalem was now the cosmic center. The Israelite king in Jerusalem was advised to rule like a Mesopotamian king at the new cosmic center. He was to make his name great as Solomon did in building the temple.

So at least claimed one political party in ancient Israel. However, there was another political party, the Levites or Mushites who claimed the law came first. They objected to the claim that Yahweh had sanctioned the royal way of life in Mesopotamia as the Nimrod author had written. Yahweh had first appeared at Sinai to Moses and the law was revealed there. They mocked the Mesopotamian way of life by writing the Tower of Babel story. Look at those mighty stairways to heaven! They all were built for naught. All those mighty and grandiose empires crumbled into dust, lost to history until recovered by archaeologists. It was the law which endured and ruled even when kings and temples were no more.

Exodus 1817 Moses’ father-in-law said to him…19”Listen now to my voice; I will give you counsel, and God be with you! You shall represent the people before God, and bring their cases to God; 20 and you shall teach them the statutes and the decisions, and make them know the way in which they must walk and what they must do. 21 Moreover choose able men from all the people, such as fear God, men who are trustworthy and who hate a bribe; and place such men over the people as rulers of thousands, of hundreds, of fifties, and of tens. 22 And let them judge the people at all times; every great matter they shall bring to you, but any small matter they shall decide themselves; so it will be easier for you, and they will bear the burden with you. 23 If you do this, and God so commands you, then you will be able to endure, and all this people also will go to their place in peace.”

The Babel author highlighted the folly of the Nimrod story ambitions. This author was anti-Aaronid (golden calf story) and anti-monarchy (the Jethro constitution).

Jethro and Nimrod offer two different models of political organization: the rule of law and the king who makes his name great. Two political parties offered two different versions of how society should be organized: one based on the rule by a king and one based on the rule of law. The result was an original narrative now separated into two narratives with different endings to the first cycle of stories. Nimrod and Babel are inconsistent because they originally part of two different narratives based on a common core. Only when they were combined centuries later were the inconsistencies juxtaposed. Imagine having to combine Confederate and Union descriptions of Lincoln and Lee in a single narrative! Again, that was a political process and not a scribal one.

For the first centuries of Israel’s existence, it had had no king. Therefore no one was in a position to abuse power. Only when Israel had a king could someone be a law unto himself. We will never know if ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia debated the powers of a king when he first ascended to the throne in Egypt and descended to the throne in Mesopotamia. But we do know the debates ancient Israel had on the powers of the king. It decided there should be checks and balances on the power of the king. No one was above the law. Even David could be called to task: “Thou art the man.” And when he was confronted he repented.

The best time for the initial battle over whether Jerusalem had replaced Mesopotamia as the cosmic center occurred when Israel could if it were so inclined think of itself it such grandiose terms. This happened when Egypt and Mesopotamia were weak (and Pharaoh’s daughter was an Israelite queen). It happened before the time of Sheshonq and Assurnasirpal II.

This approach is based on the stories originating in a political context as Levites, Aaronids, and Jebusites battled for power. Even stories set elsewhere were always about internal politics. Obviously this scenario is speculative and cannot be proven but it does illustrate how a political approach can produce a different historical reconstruction.

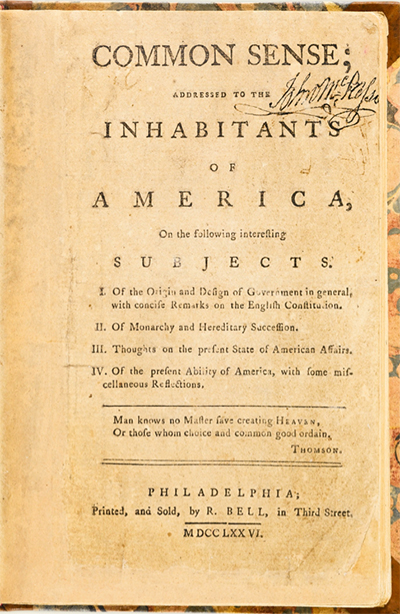

This ancient Israelite dialog on the rule of law and the rule by the king continues on in the United States. In 1776, Thomas Paine wrote in Common Sense:

…that in America the law is king. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be king; and there ought to be no other.

Once again as in ancient Israel and during the American Revolution, the issue of the rule of law versus the rule by king is being played out. Will the United States be governed by the Constitution or a Nimrod?

For more on the stories of Nimrod and the Tower of Babel see my book Jerusalem Throne Games: The Battle of Bible Stories after the Death of David.