Universities and the Legacy of Slavery: A Roundtable

This session was a new one added at the conclusion of the conference. It was not in the program booklet and may have been overlooked. The panelists spoke about the situation in their own school. Background material plus some developments since the conference have been added.

Annette Gordon-Reed, Harvard University

Her comments focused on the Harvard Law School and not the entire university. As a result she suggested, the scale of the conflict may have been smaller than incidents at other colleges particularly if undergraduates are involved elsewhere. She contrasted the situation in dealing with older law school students and teenage undergraduates perhaps away from home for the first time. Gordon-Reed may have been referring to events at Yale addressed by another panelist (see below).

As reported in The Crimson, according to the traditional view, Isaac Royall, the founder of the law school in 1817, inherited the wealth to fund it from his slave-trader father. The Harvard committee commissioned to study the situation discovered that he had died in 1781, he bequeathed money to the college and not to the law school, and that the shield was created in 1936 without awareness of any potential connection to slavery.

The Royall family crest contains sheaves of wheat which became part of the Harvard Law School shield. It had been part of the campus and of tours for years without incident. Now it has become an existential crisis for many African-American students. She personally is opposed to changing it, the decision made by the University. In her dissent [available as a PDF] to the committee recommendation, Gordon-Reed wrote:

…the burning question for me has been, “What would be the best and easiest way to keep alive the memory of the people whose labor gave Isaac Royall the resources to purchase the land whose sale helped found Harvard Law School?”

She suggested a contextual approach which as it turns out was a recurring theme in how to approach this type of problem. She wrote:

Maintaining the current shield, and tying it to a historically sound interpretive narrative about it, would be the most honest and forthright way to insure that the true story of our origins…

Gordon-Reed contrasted the Law School shield with the Confederate flag: the former was not created and has not been viewed as a symbol of slavery whereas the Confederate flag [in its various forms] represented a people at war with the Union over the issue of slavery. Wheat as a symbol evokes no such connotations. Nor does it exalt a specific individual the way a statue does.

Instead the current issue and pending bicentennial provides Harvard Law School with an opportunity to take a leadership position:

We are coming upon our 200th anniversary. This would be a perfect time to re-dedicate the Law School and the shield—making explicit our debt to the enslaved and our commitment, in their memory, to the cause of justice.

Historians in particular have a special role to play in this process:

Thanks to historians, we have “new knowledge” that we are joined in history to a group of people entrapped in the tragedy of the Atlantic slave trade. This also joins us to the larger American story of slavery. We should take this knowledge and run with it, not away from it.

In the panel session itself, Gordon-Reed acknowledged the need for people to feel at home while at school. She offered no resolution to the situation since she doesn’t have one. Her advice is for the people involved to keep talking to each other.

An example of such conversation including with her just occurred when the Thomas Jefferson Foundation hosted a public event, “Memory, Mourning, Mobilization: Legacies of Slavery and Freedom in America” at Monticello which drew 2000 people. The meeting featured commentaries from a dozen participants, including historians, descendants of those enslaved at Monticello, cultural leaders and activists engaged in several far-ranging conversations on the history of slavery and its meaning in today’s conversations on race, freedom and equality. My impression from the report by the University of Virginia is that these conversations were more preaching to the choir than an attempt at “come let us reason together” among different constituencies. At the meeting, Marian Wright Edelman, Children’s Defense Fund, asked, “How can we close the gap between creed and deed?” Did the public event generate any suggested resolutions or were the participants as stumped as Gordon-Reed as to what to do in the real world when confronted with people who disagree with them?

Craig Steven Wilder, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

His presentation addressed the wider issue of the community. He noted the widespread connections between the slave trade and colleges during the early republic. Even the later founding of MIT in 1861 was part of this process as cotton manufacturers required engineers to improve productivity and profits. In general, he observed that the antebellum image was a popular one for colleges in the 20th century.

Today, there is an increased divide between the campus and the surrounding community. He witnessed increased policing on campus. He called for an inclusion of staff and the surrounding community in the discussion of what MIT should do.

According to a published report on the situation at Calhoun College, that is precisely what did not happen at Yale:

But if Menafee’s broomstick broke the historical silence, is a voice missing from the planning process? As historian Craig Steven Wilder noted on Democracy Now!, while alumni and administrators have led debates on addressing controversial symbols on campus, “Excluded from the conversation have been the people who actually clean our offices, cook our food, move the campus buses around. But they actually spend a lot more time being impacted by those sort of visual reminders of slavery than most of the rest of us do.”

Julia Adams, Head of Calhoun College, Yale University

On April 26, the student survey results were reported in favor of a name change for Calhoun College.

On April 28, Yale decided to retain the name Calhoun College. As reported in the Yale News

University President Peter Salovey said the:

University will keep the name so that the community remembers “one of the most disturbing aspects” of its past, rejecting the demands of student activists who argue that the name honors a white supremacist.

He continued:

Erasing Calhoun’s name from a much-beloved residential college risks masking this past, downplaying the lasting effects of slavery and substituting a false and misleading narrative, albeit one that might allow us to feel complacent or, even, self-congratulatory.

Yale did not support the erasing of history, an argument similar to what has been voiced in the South regarding the Confederate history.

Julia Adams, the panelist in this SHEAR session, said she anticipated a period of reconciliation within her college during which students and administrators will work to heal deep-seated divisions over the naming dispute. Adams invited Calhoun students to an evening meeting at her house to discuss the issue, but the session was attended by just a couple dozen students and ended after only half an hour.

“I remain really proud of the Calhoun students for the way they handled this over the course of the year,” Adams said. “They lent real depth to the discussion, and I think it’s made a difference to the seriousness with which the decision’s been made.”

On April 29, the Yale students held a renaming ceremony for Calhoun College.

In the panel session, Adams reaffirmed her opposition to dropping the name “Calhoun” from the college. She again proposed “Calhoun-Douglass” as a more fitting name given the “dialog” between the two of them. [Note: she means Frederick and not Stephen.] She also drew on the favorable imagery of the antebellum way of life which had been redefined in the 1930s as the “Lost Cause,” a lifestyle violently disrupted by the Civil War. The renaming of Calhoun College would be just one step in an ongoing process of re-evaluating the legacy.

Gordon-Reed asked why the college was even named after Calhoun in the first place. My personal reaction is that the desire to name the college after someone southern probably preceded the selection of the individual name.

Yale’s decision to retain the name was not received favorably by the faculty who made their displeasure known. The school has now established a panel to review the situation. Historians figure prominently in its membership. As reported:

John Witt, the committee chair and a professor of history and of law, said the panel is strengthened by faculty members who have spent their careers studying race. Instead of having to produce a recommendation on a specific building, he said, they can think about the implications of such names in broader terms.

“It’s the promise of scholarly expertise and serious engagement with questions about history and questions about historical memory,” he said. “We’ll be in a pretty good position to be able to step back, away from the political controversy of the moment, and identify principles that might be enduring and last for the university.”

Mr. Witt said he hoped that the committee would create a model for other colleges.

The effort will include contextualizing the process whereby buildings were named excluding those buildings named directly after the donor who made the building possible where the context is obvious.

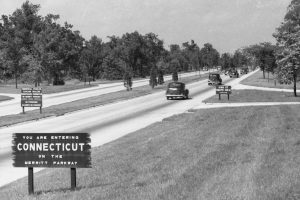

In response to a question from me, Wilder contrasted the use of a racially provocative name versus names which have a racial heritage. This distinction seems important to me. For example, I drove to the conference on the Merritt Parkway. The Merritts owned slaves but the name is hardly associated with slavery. Should the parkway be renamed because students driving to Yale may be traumatized? The answer is “no” based on the comments by Gordon-Reed and Wilder.

Given how widespread and intricately intertwined slavery is to American life, excising the name of anyone associated with it probably is a fool’s errand which would result in every road being renamed after a tree or a number. Wilder suggested we learn from the experience of former colonies in how they handled the names carried over from colonial times into independence. He also noted the constant change in demographics. Gentrified whites in Brooklyn don’t necessarily cotton to having streets named after Malcolm X! There are times and people who want to live on streets named after Jefferson Davis and Malcolm X and there are times and people who don’t. Who makes that decision and is it irrevocable?

As it turns out, this precise issue has been playing out in Alexandria, not at a college, but in a parkway as reported in the Washington Post. The Alexandria City Council voted unanimously to change the name of Jefferson Davis Highway and seek permission from the Virginia General Assembly to move a renowned statue of a Confederate soldier in historic Old Town. The pensive and unarmed south-facing Confederate soldier would be moved to a local history museum on the same corner of its present location. Erected in 1889 and owned by the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, it bears the names of Alexandria residents who died on behalf of the South. According to a published report:

“If this were on Monument Avenue in Richmond, where it is clearly [celebratory], I’d say knock it down,” said council member Timothy B. Lovain (D). But the statue is a reminder of the costs of war, he said. If it can remain at the same historic corner, with additional context explaining its significance, and be removed as a traffic hazard, the relocation might be politically possible.

Note the use of the word “context” again. The council deliberations and public debate occurred in a chamber where a portrait of Robert E. Lee hangs opposite one of George Washington and where the painted backdrop behind the council is of Alexandria during its Union occupation. The discussion then turned to street names. Various legislative actions at multiple levels may be required depending on the changes requested.

This debate highlights some of the very concerns raised by Wilder and Gordon-Reed in the session. The college debates are not occurring in isolation from events outside the academy.

In the Q&A portion, a dean from a school in Baton Rouge reported on establishing a link with Georgetown in a 2017 class in recognition of the people sold by Georgetown to slaveowners in Louisiana. Perhaps next year there can be an update on how the still-fluid situation with Georgetown worked out. The post-conference developments highlight that an even more contentious issue may be lurking in the shadows than the “simple” action of renaming a building or parkway, relocating a statue, or giving scholarships to descendants. That issue is money. As the discussions shift to someone paying money to someone else one may anticipate even more intense “conversations” about who is going to get stuck with the bill and what will be done by the recipients with the new-found money.

Another question was raised regarding the increased disparity between the students and the staff. If a college outsources work such as the maintenance of the grounds than the staff is less connected to the college than would have been true in the past, apparently referring to the situation at Yale where precisely such a worker initiated the most recent contretemps.

One person observed that the Calhoun alumni were dedicated to their college by that name. This means Gordon-Reed’s plea that students should feel at home had worked for these graduates. A change in name therefore was a violation of their home. In other words, for alumni, Calhoun isn’t simply a name but a word that conjures up all the associations a graduate has with the college. The name has no intrinsic meaning but it is the name of their college, embedded in their memories, and not to be tampered with. If be it ever so humble there is no place like home, what message are you delivering when you tamper with that home?

The questions raised in the session of course extend beyond the college campus. One person in the audience reported on the presence of Confederate flags in multiple states in New England. How does one teach the historical reality of slavery in a “post-slavery” college? What strikes me is that despite all the actions of the civil rights era in the 1950s and 1960s, for the first time in American history, we actually may be at a point where we can have an intelligent discussion about the role of slavery in the American history, how it enabled others to live the American Dream, whether the descendants of those slaves have the same right to live the American Dream (Martin Luther King) or if they should reject it, and the place of the Confederacy in American history. These developments are occurring at time when the demographics of America no longer neatly divide into black and white (even with the one-drop rule) as there are more and more people here not from Europe and Africa and even the black people here didn’t all arrive via the Middle Passage (biracial Barack Obama). I do not mean to suggest that We the People will have these conversations, only that there is a more realistic chance to have them than has ever existed in American history.

All in all, a rather open-ended session to end the conference on an issue that is sure to be with us a nation for years to come.

(Photos courtesy of the Harvard Law School, Washington Post, and State of Connecticut)