America has always been a diverse country. America has always been a country of multiple ethnicities, multiple races, and multiple religions. The individual peoples have changed over time. Generally the number increases, but we have always been a country of numerous different peoples. Yet we also are the country of We the People, the opening words on the document that constitutes us a nation. How can we be both?

When I was growing up, there were the three “I’s” in New York City mayoral elections – the Irish, the Italians, and Israel meaning the Jews. Candidates needed to show deference and pay homage to each of the groups. Whether they did so out of any ecumenical belief or the hard reality of practical politics is another matter. Still there were these three groups. Intermarriage then was an Italian-Irish marriage even though both people were white Catholics.

Yes, there were blacks in New York City then, too. They did not have a specific homeland beyond the continent of Africa. As a result, there was no country for a candidate to visit. Instead they trekked to Harlem, the cultural capital of middle-passage blacks since the 1920s and the Great Migration.

Of course, as West Side Story reminds us, these groupings were about to increase by one.

David Hackett Fischer

On an academic level, I became more aware of the diversity of the United States through Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America by David Hackett Fischer. As the title indicates, the book divides the English or British into four distinct groups of folkways. He identified them as:

The Puritans who famously settled in Massachusetts and the surrounding areas

The Quakers who tended to be limited to one colony, Pennsylvania

The Cavaliers who started in Virginia but spread to other southern colonies

The Scotch-Irish who tended to be located in the border lands, the back country or fringe areas.

So rather than view the people from Great Britain monolithically, one should understand them as four distinct peoples or folkways.

These folkways brought their lifestyle with them when they emigrated to the colonies. Fischer lists various characteristics by which he defines each folkway in the area of Great Britain where they lived. Then he traces each characteristic or its equivalent to the life they created when they arrived here. In general terms, Fischer finds they each folkway transplanted their way of life from the old world to the new. Thus to claim that the English settled America obscures the reality of the situation – four different peoples settled here.

Fischer continues the story beyond the colonial era. He tracks the migrations of these peoples across the United States as it expanded westward. Most famously are the New Englanders who became Yorkers around the time of the Erie Canal. They kept moving west across the northern portion of the country. Their distinctive trait was doing something they already had done in the 1600s in New England – start a college.

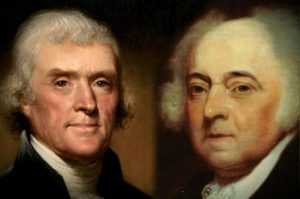

He concludes by identifying the folkway to which the individual American presidents belonged. The early domination of the Cavaliers (Virginians) and New Englanders (Adams father and son) are obvious. Today we have no appreciation for the significance of the election of Andrews Jackson, the first of many Scotch-Irish presidents. Now he is just a dead white male; back then he was our first diverse president.

Overtime, it became harder and harder to assign a folkway to an individual president. The complication was due to intermarriage. I am referring not only to intermarriage among these four groups but with other groups. Consider the situation just in New York where I live. In addition to the British folkways there were Dutch, French Huguenots, German Palatines, and Sephardic Jews (actually the Bronx was named after a Swede who married a Dutch woman and this explains why in Sweden there is a Yankee aka Bronx Bombers following). In time there would be Dutch and German presidents often with a connection in biology or spirit to an English folkway.

Returning to the New York, there were another group of people who often have been overlooked. Irish William Johnson was the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs. In the course of his work, he dealt not only with various European peoples noted above, he dealt with various Indian nations as well. At that time, Algonquin, Haudenosaunee, and Lenape were not all just one indigenous people. For that matter, neither were the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Seneca, Oneida, and Tuscarora all just one people. Imagine lumping Koreans, Vietnamese, and Chinese together as one people today! Johnson is an unsung figure in America history who engaged the diversity of the peoples here more so than any other individual in the 18th century.

Colin Woodard

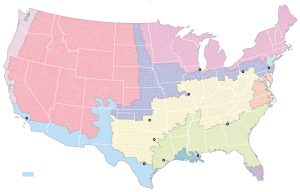

Recently, Colin Woodard, has continued this line of thought. He is the author of American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. As the title suggests, his purview extends beyond the four folkways analyzed by Fischer. Woodard certainly is aware of Fischer’s work and he has expanded on to reflect the greater diversity which exists today. On July 30, in an opinion piece for the New York Times, “The Maps That Show That City vs. Country Is Not Our Political Fault Line: The key difference is among regional cultures tracing back to the nation’s colonization,” Woodard applied his template to the recent presidential election.

[O]ur true regional fissures can be traced back to the contrasting ideals of the distinct European colonial cultures that first took root on the eastern and southern rims of what is now the United States, and then spread across much of the continent in mutually exclusive settlement bands, laying down the institutions, symbols and cultural norms later arrivals would encounter and, by and large, assimilate into.

In other words, New York is still a commercial city (thank you Dutch) and Boston is still a college city thank you Puritans).

His analysis tracks 11 different groups.

Tracing our history, I’ve identified 11 nations, most corresponding to one of the rival European colonial projects and their respective settlement zones. I call them Yankeedom; New Netherland; the Midlands; Tidewater; Greater Appalachia; Deep South; El Norte; the Left Coast; the Far West; New France; and First Nation. These were the dominant cultures that Native Americans, African-Americans, immigrants and other vital actors in our national story confronted; each had its own ideals, assumptions and intents.

Through a series of colorful maps, Woodard then compares the vote percentages from 2016 to these cultural demographics. His explanation for the stark differences he finds in each of their choice of presidential candidates is:

Why the differences? I’ve long argued that United States politics resolves around the tension between advancing individual liberty and promoting the common good. The regional cultures we think of as “blue” today have traditions championing the building and maintenance of free communities, today’s “red” ones on maximizing individual freedom of action. Our presidential contests almost always present a clear choice between the two, and the regions act accordingly.

Take a simple and well-known example not in the article: healthcare. The “individual freedom of action” or “don’t tread on me” faction despises being told what to do and having no choice about it. Whether a law is in their best interest is secondary to whether it is being imposed on them by condescending arrogant self-righteous elitists or not (the 2010 election). And why should the Democrats try reasoning with such people in the first place? As Junior Trump said, they are not even people. Oh wait. He was talking about the Democrats. How can there be “come let us reason together” when neither side can acknowledge the humanity of the other?

University of Pennsylvania

In the commencement address this year at the University of Pennsylvania, college president Any Gutmann said:

The great seal of the United States reads E Pluribus Unum: From Many, One. Graduates, during you time here, you have come to know the Red and Blue version we hold so dear: E Pennibus Unum: From many Penn People, One Penn Family…

Putting aside the boosterism for a moment, she defined that unity as:

Liberty not chains, opportunity without limit, love without condition, and learning without end.

She certainly is right to note the college experience as a bonding experience for those who can afford Ivy League colleges. On a cheaper scale, being part of a band of brothers also can bring people together. The new exhibit “Comeback Season: Sports after 9/11” at the 9/11 Memorial addresses the same point. Richard Sandomir in “As America Grieved, Sports Helped Console Us” (NYT 8/10/18, print) recently wrote about the exhibit:

Sports may not always seem important ─ they’re just games, aren’t they? ─ but they are tribal events that unify people in large communal settings for a common purpose.

Remember when all Americans including those in Jersey City chanted “U.S.A.! U.S.A.! U.S.A.!”

In contrast to Gutmann, an Iranian Jewish immigrant Penn alum who has embraced being an American citizen offered a more emotionally intense perception of E Pluribus Unum then she finds at Penn, Harvard, Yale and Princeton:

[W]e lovers of America want to conserve the Constitution with its entire Bill or Rights intact. We don’t believe in multiculturalism because we believe that “America” is the name of the one culture of this country…it’s a culture with many languages and cuisines and clothing and religion and music [FOLKWAYS]…a culture that all of us from varying backgrounds embrace and love with all our hearts. It is the culture of freedom. That’s the only culture I feel a part of right down to my bones. E Pluribus Unum ─ out of many, one ─ is printed on our coins. Out of many peoples, we form one culture as Americans.

Right now the Democrats and the Republicans are in agreement in rejecting these words. One party slices and dices the American people into as many hyphens as it cans with the intent of cobbling together a winning coalition. The other party relies on one big hyphen that actually combines multiple folkways but only with one race. No candidate or prospective candidate champions the E Pluribus Unum mantra.

So whither America? A nation of “Fellow Americans” or a nation of tribal rivalries? We know where John McCain stood. But he is dead and there is no one now to pick up the torch.

Peter,

A great read; thx. I have Albion’s Seed, but have been intimidated by it’s massive content. I will read it, but you gave a wonderful

summary. I do teach the Scots-irish story in great detail, and yes,Andy Jackson as our first SI President from the backwoods.

One modest update: Quakers, for sure, in PA, but do recall that Roger Williams, when escorted out of the MA Bay Colony, started RI as a Quaker refuge. He later converted to Baptist. Perhaps more action during the Sunday services. Good man, in either case.

Bob Ulrich

Thanks Bob. Give the book a try. It certainly is a big one but it is worth it.

Thanks, Peter. I was not aware of the Woodward article.

Tim

Timothy S. Good

Superintendent, Lincoln Home National Historic Site

Interim Superintendent, Ste. Genevieve National Historical Park

National Park Service

https://www.nps.gov/liho/index.htm

https://www.facebook.com/LincolnHomeNHS/

217-391-3222

Thanks Tim. Please make sure you search for “Woodard” and not “Woodward.” I have made that mistake a few times myself. Peter

Keep up the great reporting and the provocative stories and analysis

A heroic effort that deserves our thanks

Best

Roger Panetta

Thanks Roger and for all that you have done for Hudson Valley history. I hope it all makes a difference. Peter

Brilliant column, Peter. (I am loath to call them “blogs.”) Is there a permalink online? I’d like to share.

Cheers

Steve

Thanks Steve but I think a column has to be posted in a newspaper, journal, or magazine. I did send this to the press including to your contact but it is much to long to appear in a newspaper.

There are links in blog under print and comment and you should be able to share it directly from the blog itself.

The url is https://ihare.org/2018/08/28/fellow-americans-versus-tribal-rivalries-whither-america/

Your help in spreading the word is appreciated. Peter

I grew up in Scranton PA. We had pioneer Welsh who’s ancestor Cousin Jacks worked the mines.Poles, Russians, Ukranians. Italians from parts of Italy, different from one another as Swedes from Hottentots. Irish the same, Jews alsos..Gliz, Yeki…What a polygot. Mr. O’Hara would not go to that “Ginny church” in he Flats for his sonJoe’s wedding so it was held “among OUR people” in the Immaculate Conception. In the Navy in WWII I lived with still more diverse cultures. My visits to my Mohawk friends up in Hogansberg was living in a separate universe. And my Norwegian friend’s family..How we all form a workable government…??????

You are certainly right about World War II. It brought together a lot more people and for a lot longer than 9/11.

Peter – missed you in Albany last Friday, sorry about the car trouble.

In 1968, after military service over seas I joined the wonderful people at Eastman Kodak Co. One of the first people that took me under his wing was a fellow named Boris Yovanoff (in Macedonian, Yovanoff means “son of John” or Johnson). Boris and his wife and daughter had just returned from an extended vacation around Europe. They ended their stay in Macedonia (sometimes part of Greece, sometimes an independent country.

Macedonia was Boris’ family homeland. Even then there were two cultures there never to come together of mix in any way. Two villages could be only a mile apart on opposite sides of a hill. One village Macedonian Orthodox (eastern church related to Greek Orthodox). The village on the other side of the hill was Muslim and had been for a very long time. They were both Macedonians yet there a hatred across that divide that prevented “any contact”. As we now know, these types of divides exist all over the world. Somehow we here in the Americas have been able to transcend these divides. We may disagree…we may even not really trust some but never to the point of not sitting down and breaking bread together. This is what makes us special I guess. I use the word “special” not to intone a sense of superiority in any way. You can just say that we lucked out somehow and that is enough.

As always, Thank you, Peter

Your welcome, but as we segregate into congressional districts of our own kind I have become more concerned about what is happening here.

I just read your article on tribal rivalries. I had never thought about the differences in early ‘English’ settlers. Interesting article!