Move over Gilgamesh and Enkidu. Stand aside Hector and Achilles. The biblical O.K. Corral is back. The ultimate showdown at high noon has returned to the small screen. The “House of David” has premiered on Amazon Prime Video. It is part of the original faith-based programming that made “The Chosen” about the life of Jesus Christ one of the most successful crowdfunded television projects of all time.

“The sheer size of the audience is enormous” said Jon Erwin of Wonder Project who pitched “House of David” to Amazon and co-directed several of the first season’s eight episodes. The team behind “The Chosen” estimate more than 280 million unique viewers, a third of whom say they are not religious.

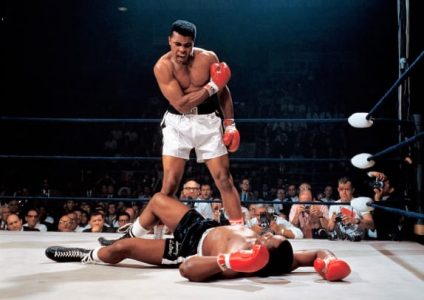

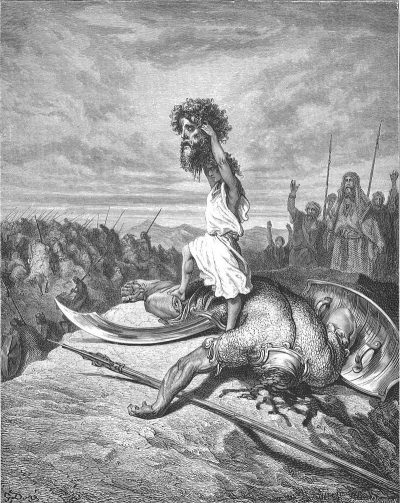

The series opens with a big scene: the battle between David and Goliath. In this version, Goliath pierces David with a spear only to have the bleeding young shepherd reach for a rock, a non-biblical incident.

For this show, pastors, historians, biblical, and rabbinical scholars were consulted for accuracy. Script writers were needed to put words into the mouths of adored figures. Snappy dialog is needed. New scenes to connect the dots are needed. Pseudo-Shakespeare is to be avoided. Some viewers of “The Chosen” may consider the changes blasphemous.

“The Streaming Rush to Turn Scripture into Scripts,” Annie Aguiar, The New York Times, March 2, 2025.

“’House of David’ Sets Giant Goliath against Bible Action Star Slinger,” Bryan Alexander, USA Today, March 3, 2025, posted in The Journal News

GOLIATH

The figure of Goliath is played by Martyn Ford. The “Mortal Kombat” star and MMA fighter stands 6-foot 8-inches tall. Not to worry. The heavily muscled actor has been digitally enhanced to be the requisite height of nine-feet nine-inches. A voice coach helped him down-play his British accent while in post-production his voice echoes with terrifying sound into a worthy bellow that intimated and terrified the entire army of Israel for forty days.

So what are the questions to be raised?

2 Samuel 21:19 And there was again war with the Philistines at Gob; and Elhanan the son of Jaareoregim, the Bethlehemite, slew Goliath the Gittite, the shaft of whose spear was like a weaver’s beam.

As it turns out there is another biblical version of the death of Goliath. Here it is one of David’s warriors who does the deed and slays Goliath. Many people have twisted themselves in knots trying to reconcile these two versions of the death of Goliath.

Fortunately, there is a straightforward answer that may upset those who take the Hebrew Bible as physically literally true. In the biblical story itself, the Philistine is rarely referred to by the name “Goliath,” in fact, only twice (RSV). Otherwise he is simply designated as the/this Philistine throughout the 58-verse story. Even in the actual showdown, David does not refer to him by name. The resolution to this apparent dilemma is that in the original version, the Philistine warrior was unnamed. The name “Goliath” was later inserted into the story but the historical Goliath was not David’s foe. The historical Goliath had been dispatched by one of David’s own warriors.

There are two key points to recognize here:

1. the original author knew that David had not killed Goliath but so what? He was not writing a biography or history of David, he was writing a story.

2. the original author knew that no Philistine was nearly 10-feet tall. The author chose to make the Philistine warrior that height.

In other words, the author has created a monster. He has transposed a mythical figure from a story of cosmos and chaos and situated him in an historical setting. The Philistine is nameless because this is a story where the hero slays the dreaded foe. In this case the Philistine giant represents all the Philistine warriors who have threatened the Israelites. He is no more real than Uncle Sam or the Russian bear. The audience knows the monster has to be slain, that the Philistine threat has to be eliminated. They are looking for the hero to do so.

THE RIGHT STUFF TO GO INTO THE ARENA

Normally, one would expect the king to go forth into battle to vanquish the enemy. It would be no surprise if the king was the one who ventured forth. But the king is old here and past his prime. He needs someone else to go forth. For me this is a clue that the original story was told after Saul had died in battle against the Philistines. The account in I Sam. 31 seems quite realistic in its depiction of the Battle of Gilboa where the Israelite king is stripped of his armor and decapitated.

The next choice to face the Philistine warrior would be Jonathan, the son of Saul. Jonathan was a warrior of some repute who had his own victories against the Philistines at Geba (I Sam 13) and Michmash (I Sam 14) again in stories that seem realistic. Jonathan too dies in the battle at Gilboa against the Philistines. When David hears the news he laments their deaths, a lament that is to be written down and taught.

2 Samuel 1:17 And David lamented with this lamentation over Saul and Jonathan his son, 18 and he said it should be taught to the people of Judah; behold, it is written in the Book of Jashar. He said:

19 “Thy glory, O Israel, is slain upon thy high places! How are the mighty fallen!

20 Tell it not in Gath, publish it not in the streets of Ashkelon; lest the daughters of the Philistines rejoice, lest the daughters of the uncircumcised exult.

21 “Ye mountains of Gilboa, let there be no dew or rain upon you, nor upsurging of the deep! For there the shield of the mighty was defiled, the shield of Saul, not anointed with oil.

22 “From the blood of the slain, from the fat of the mighty, the bow of Jonathan turned not back, and the sword of Saul returned not empty.

23 “Saul and Jonathan, beloved and lovely! In life and in death they were not divided; they were swifter than eagles, they were stronger than lions.

24 “Ye daughters of Israel, weep over Saul, who clothed you daintily in scarlet, who put ornaments of gold upon your apparel.

25 “How are the mighty fallen in the midst of the battle! “Jonathan lies slain upon thy high places.

26 I am distressed for you, my brother Jonathan; very pleasant have you been to me; your love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women.

27 “How are the mighty fallen, and the weapons of war perished!”

Jonathan was a hero in his own right. Yet he does not appear in the story of David and the Philistine warrior. For me this is a clue that the original story was told after Jonathan had died in battle against the Philistines.

Finally, there is a third son of Saul who deserves to be mentioned, Ishbaal (various spellings). He has no stories to tell of battles he has won. He does not appear in the story of David and the Philistine warrior. His appearances in II Sam. 2-4 describing his conflict with David. He is a weak king who fears Abner, his military leader. Ishbaal is murdered in his sleep and is decapitated. I don’t know how many of these decapitations will be shown in the TV series. In any event, there is war between Ishbaal, king of Israel, and David, king of Judah Hebron.

I suggest the story of David and the Philistine warrior should be situated in exactly this time when Israel including the aforementioned Abner has to choose between David, a military warrior and hero, and Ishbaal, a weak ruler. The author of this story of David and the Philistine warrior presents the case that David is the better choice. He is not writing history or composing a biography. He is not writing literature or theology although he is skilled in those areas. He is telling a story of David and the Philistine monster representing the Philistines who have terrorized all Israel that David is the superior choice to be king of Israel. He even has David use a sling, a weapon of Saul and the tribe of Benjamin, to deliver the message

1 Samuel 17:45 Then David said to the Philistine, “You come to me with a sword and with a spear and with a javelin; but I come to you in the name of the LORD of hosts, the God of the armies of Israel, whom you have defied. 46 This day the LORD will deliver you into my hand, and I will strike you down, and cut off your head; and I will give the dead bodies of the host of the Philistines this day to the birds of the air and to the wild beasts of the earth; that all the earth may know that there is a God in Israel, 47 and that all this assembly may know that the LORD saves not with sword and spear; for the battle is the LORDS and he will give you into our hand.”

This is great writing from someone 3000 years ago from someone who had front row seats to the conflict between Ishbaal and David and who wrote one of the earliest political op-ed pieces in history.