“What we’ve got here is failure to communicate.” These words uttered to Paul Newman in the movie Cool Hand Luke (1967) have become part of American folklore. They attest among other things the challenge in effective communication. As anyone who writes or speaks in public (and even in private settings) knows that while you know exactly what you mean by your words, the reader/listener is quite capable of reading/hearing something totally different. The issue then may become one of trust: Is there sufficient trust between the two of you so that you can resolve the miscommunication or do you both go your separate ways sure that you heard or read right and let the difference become a sore point that festers possibly even into violence?

You talkin’ to me?

THE UNIVERSAL TRANSLATOR

The universal translator is a beloved device of science fiction such as in Star Trek. It instantaneously enables people of different worlds to perfectly understand each other. In theory, it could work as well between beings of the same world who speak different languages.

Even more miraculously, the device requires only a few words to work its magic. All one needs to do is say the equivalent of “Hello, my name is John Doe” and the device comprehends the entire culture. It knows that Alexander Graham Bell invented “hello” so he would have something to say when using the phone and why Henry Stanley said the now-awkward, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume.” Through this device all cultural nuance vanishes as it precisely translates the words of one language and species into the American English of the 1960s or 1980s-1990s depending on which Star Trek series you are watching.

Sometimes the translation does not work. Times change. In the Whales movie (Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home), Kirk says at the goodbye moment with the 20th century scientist now in his present and her future: “like they say in your century, I don’t even have your telephone number.” If the movie were made today, would the comment even be about telephone numbers? Remember “when you’ve got mail” did not refer to the Post Office and was something exciting?

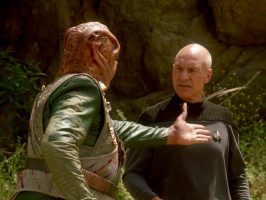

In a Star Trek Voyager time-travel episode (Season 3, Episode 8-9: “Future’s End: Parts 1 & 2”), Tom Paris, supposedly conversant on 20th century America, learns that he is not quite as familiar with 1996 vernacular as he thought. He keeps flubbing the references and terminology of the American past. Perhaps most famously, in a Star Trek: The Next Generation episode, the Enterprise encounters a people who speak in metaphors and not physically literal. The universal translator is useless.

The captains of the two species share an experience which each one explains in their own language: Picard tells the story of Gilgamesh in our narrative format while the alien uses metaphors and symbolic language to express beings who are alone and then who join together as brothers in face of a common foe. The new metaphor Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra then joins Gilgamesh and Enkidu at Uruk. These examples highlight the challenges in effective communication between species and between time periods of the same species.

These science fiction examples are relevant because it is perhaps with Europeans and Indians that we have the most tragic close encounters of the third kind in human history.

I

“To be or not to be, that is the question?” Shakespeare posed a fundamental question of identity through the character of Hamlet. The question is known far and wide.

One answer frequently is overlooked. “I am that I am, that is the answer.” In the King James Version of the Bible translated approximately the same time as Shakespeare wrote Hamlet, the name of deity Yahweh who Moses encounters at the burning bush is translated as “I am that I am.” The validity of this translation of the Hebrew has been questioned by biblical scholars. The Hebrew appears to be in the third person and not the first person. It seems more likely that the not-so-universal translators of the King James Bible were influenced by the cultural values of their own time. One should not be surprised by this. All biblical translations are not alike.

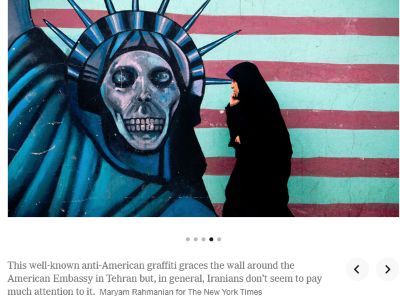

The consequences of this failure in translation are not limited to the ivory tower. In fact, the translation is not so much a failure as an expression of fundamental English values. The English are an “I” people. They brought that perception with them to what became the United States. There they encountered people colloquially called Indians who had a different value system. The tragic result was that even when people thought they were successfully communicating with each other, they were not. Those miscommunications continue to this very day. As best I can tell, there is little hope in the foreseeable future that each peoples will learn to speak the same language or even try to understand each other.

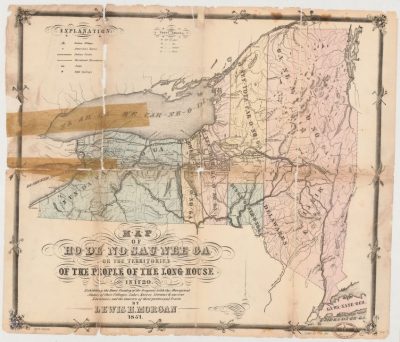

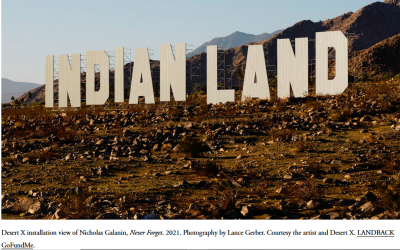

LAND

The initial failure to communicate occurred over land. The Europeans brought to this country a value system based on “I.” I own this piece of land. I have a deed attesting that I own this land. The “I” could be an individual human being or an individual corporation. It meant that through a treaty [which later would be broken anyway] you Indians who owned the land sold it to me and/or my corporation. The land was purchased and not taken from you. It now belongs to me.

As is comparatively well-known today, this perception did not match how the Indians understand the transaction. They did not come from an “I” society with deeds. The European concept of land ownership was foreign to them. Typically, today, this is understood to mean something along the lines of “we grant you permission to use the land.” In this scenario, “use” did not mean permanently settle in farms and prevent us from using it anymore the way it did to the Europeans. There was a failure to communicate. So while land treaties may look nice and official, they never meant the same thing to both parties. Of course, one can make the claim that even based on the European meaning of the terminology, the treaties never meant for long to the Europeans what the treaty expressed anyway.

MASCOTS

Mascots and logos were the subject of a recent blog (Should Chief Daniel Nimham Be Honored or Erased?, December 14, 2021). As I mentioned in it, one lesson learned by me in studying the current controversies, is the difference between Indians and Americans on the choices made for logos or mascots. Americans frequently choose an individual. It doesn’t even have to be an historical person, it could be a fictional one. By contrast, the Indian images were more pictorial or metaphorical and not of an individual.

Jean M. O’Brien (White Earth Ojibwe) in a virtual talk through the Vermont Historical Society (January 19, 2022) spoke about statues to Massasoit. He was the grand sachem of all the Wampanoag Indians. He met with the Pilgrims. As best I can tell the statues of him she showed are part of the New England culture and not the Wampanoag tradition. Have you ever seen statues by Indians to one of their own? For example, the statue to Chief Nimham mentioned in an earlier blog is being done by the municipality of Fishkill and not the Stockbridge Indians. Again, different cultural values.

NATIVE

O’Brien also spoke about the word “native.” The topic came up as an objection to non-Indian New Englanders saying they were “native New Englanders.” In her opinion that was an improper use of the term.

In this instance she is exactly right and exactly wrong. “Native” in the American sense, refers to where you as an individual were born. No matter where one may travel in the world, you can always identify yourself as a native of your birth place. In American, I am a native New Yorker and a native American.

By contrast, “native” in the Indian sense used by O’Brien refers to a people, a people who have been on the land for 500 generations or 10,000 years. It is not based on individual birth. Based on her definition, the Tuscarora will never be native New Yorkers in American since they migrated to New York; the Cherokee will never be natives of Oklahoma in American since they were forced there; and the Apache will always be Native Canadians since they migrated from there to what became America.

In my opinion, Indians would be better served if they dropped the term “native” for “ancestral.” Americans rarely even use the term “native” and when they do they are referring to their place of birth. One may ask, what exactly do Indians gain by referring themselves as “Native Americans” to the exclusion of the American meaning? Consider the 14th Amendment to the Constitution:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.

Birth place of the individual in the United States makes us American citizens. So again, one may ask, what is the value added to Indians in claiming that only they are native to America and that Americans born here are not?

One final example highlights the dilemma of the failure to communicate through different meanings of the same term. In her talk, O’Brien suggested that non-Indigenous people (her only use of that term instead of Indian in her entire talk) refer to themselves as “Settlers.” American ancestors can be identified as settlers, immigrants, and colonists, but Americans in the present do not use such terms to refer to themselves as individuals (unless they are an actual immigrant as an individual). Americans as settlers refers to an action taken by an individual and not a genetic trait passed on from one generation to the next forever. Here again, one may ask how does it benefit Indians to refer to Americans in the present as non-native settlers? It sounds more like Woke run amok.

In these casual examples at the conclusion of her talk, O’Brien demonstrates the failure to communicate is in full swing. Her suggested terms simply add fuel to the fire in the culture wars. They are fine as long as she is preaching to the choir. Even though she is a calm and reasonable person, her suggestions are not words of healing, they are words of war.

In a previous blog I suggested the centennial of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act provided an opportunity for Indians and Americans to have a conversation about what it means for an individual Indian to choose to be or not to be an American citizen and on the relationship between Indian Nations and the United States.

The Onondaga Nation and the Haudenosaunee have never accepted the authority of the United States to make Six Nations citizens become citizens of the United States, as claimed in the Citizenship Act of 1924. We hold three treaties with the United States: the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the 1789 Treaty of Fort Harmor and the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua. These treaties clearly recognize the Haudenosaunee as separate and sovereign Nations. Accepting United States citizenship would be treason to their own Nations, a violation of the treaties and a violation of international law, as recognized in the 2007 United Nation Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. (THE CITIZENSHIP ACT OF 1924 by Onondaga Nation, June 7, 2018).

We also should add language and vocabulary to the mix. On the other hand, I am well aware of the fact that no such conversation will occur and the culture wars will continue and even worsen.

“In a marriage, almost never do a husband and wife have the same language. The key is we have to learn to speak the language of the other person,” Dr. Gary Chapman quoted in the NYT 2/13/22.