This blog is a continuation of a study deriving from an “Exchange” in the journal of the American Historical Association. The title of the Exchange is “Living with the Past: Thoughts on Community Collaboration and Difficult History in Native American and Indigenous Studies.” It consisted of a review of two books on King Philips War (1676) and one organization, the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association (NAISA).

The first blog I wrote on this Exchange addressed the critique of and the defense of the NAISA and its scholarship by the participants (Native American and Indigenous Studies: Another Culture Wars Episode).

The second blog on this Exchange, Violence and Native American and Indigenous Studies (NAIS), focused on the subject of violence in one of the two reviewed books. For whatever reason, the author of that book did not participate in the Exchange while the author of the other book did. The absence of the author’s participation meant the accusations about the shortcomings in the scholarship were not refuted.

In this blog, I wish to address a topic not included in the Exchange but implicit in it. This has to do with the terminology used by the scholars, specifically the words “Indigenous” and “Indian.” In many instances the author has no choice – the reference is to an organization, conference, book or article title which has the word “Indigenous” or “Indian” in it. I did not scrutinize the Exchange to differentiate between when the use of a term was the author’s choice or not. In 32+ pages of the journal, the word “Indigenous” was used 110 times. In the same space the word “Indian” was used 34 times. This roughly 3:1 ratio is not a scientific experiment. I suspect many of the 34 times the word “Indian” was used in the Exchange was because the author had no choice, for example if one was referring to the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian or the American Indian Quarterly. The question I have, in baseball terms, is what is the value added in the use of “Indigenous” over “Indian”? What is the reason for the change?

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN (NMAI)

Speaking of the NMAI, I had the opportunity to participate in three online presentations by the NMAI since I read the Exchange. In all three instances, an immediate question raised or anticipated was what to call “Indians.” Since many of the participants were teachers and the NMAI specifically was reaching out to the education community in these programs, the urgency and immediacy of this question suggests that teachers do not want to commit a politically incorrect faux pas and be hauled off before the Thought Police by a white parent of a white student claiming insensitive and disrespectful language is being used in the classroom.

The NMAI is well aware of the situation. It even has prepared a “cheat’ sheet teachers can use. In general terms the Indian and white instructors in these sessions say that the people prefer to be called who are they are whatever that particular tribe or nation name happens to be. This makes sense. One says Japanese-American about an American citizen of Japanese descent for instance. When referring to people collectively, say not to Polish-Americans but to all Americans of European descent, then the preferred terms according to the NMAI are American Indian, Indian, Native American, or Native which can be used interchangeably.

NMAI is aware that the term “Native” can be problematic. The reason is Americans born in the United States are native Americans as well (see If You Are a Native New Yorker, Are You a Native American?: The Weaponization of “Native” and the Culture Wars). In fact, since I started writing this blog I have come across multiple attestations of people being referred to as native New Yorkers or of a particular borough. True, one person’s ancestors can have been a Native American earlier than when your immigrant ancestors first had a child born in the United States, but one’s “nativeness” is determined at your birth, not by you parents or distant ancestors. At some level the NMAI may be aware that privileging one group as more “Native American” than another group can be a micro aggression to a non-Indian person born in America.

Strangely enough, the term “Indigenous” did not come up in these sessions as a suggested name for Indians. For more on this topic see Warrior, R., “Indian,” in B. Burgett and G. Hendler (eds.), Keywords for American Cultural Studies (2014). Personally, I think “Turtle Island people” or “Turtle-Island-Americans” would be a more respectful name. It draws on the actual Indian culture without privileging it.

FIRSTING AND LASTING: WRITING INDIANS OUT OF EXISTENCE IN NEW ENGLAND

The question remains what is the value added of the term “Indigenous” instead of “Indian”? One may also add what the purpose was in the invention of the term in the first place?

Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England is a book by Jean O’Brien who participated in the Exchange. The description of the book is:

Across nineteenth-century New England, antiquarians and community leaders wrote hundreds of local histories about the founding and growth of their cities and towns. Ranging from pamphlets to multivolume treatments, these narratives shared a preoccupation with establishing the region as the cradle of an Anglo-Saxon nation and the center of a modern American culture. They also insisted, often in mournful tones, that New England’s original inhabitants, the Indians, had become extinct, even though many Indians still lived in the very towns being chronicled. This book argues that local histories became a primary means by which European Americans asserted their own modernity while denying it to Indian peoples. Erasing and then memorializing Indian peoples also served a more pragmatic colonial goal: refuting Indian claims to land and rights. Drawing on more than six hundred local histories from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island written between 1820 and 1880, as well as censuses, monuments, and accounts of historical pageants and commemorations, the book explores how these narratives inculcated the myth of Indian extinction, a myth that has stubbornly remained in the American consciousness. (Bold added)

In the book there are no uses of the term “Indigenous” and 7 examples of “indigenous.” That suggests to me the usage is based on the traditional meaning as native to a place. Exactly when “indigenous” shifted to being “Indigenous,” I don’t know. The book also uses the term “Indian” approximately 1500 times. Evidently there was no problem in the Indian author using the term “Indian” and no obligation to use “Indigenous.”

On the book jacket, Philip J. Deloria, who also was part of the Exchange, wrote:

Driven by a creative reading of hundreds of local histories, Jean M. O’Brien’s Firsting and Lasting reinvigorates the old question of the ‘vanishing Indian‘ in surprising ways, taking readers into the contradictions surrounding race and modernity, and offering an ur-history of the politics of tribal termination, dual citizenship, and cultural politics.

Deloria is the author of the three books Playing Indian, Indians in Unexpected Places, and Becoming Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract.

The book jacket description of the book is:

In Firsting and Lasting, Jean M. O’Brien argues that local histories became a primary means by which European Americans asserted their own modernity while denying it to Indian peoples. Erasing and then memorializing Indian peoples also served a more pragmatic colonial goal: refuting Indian claims to land and rights. Drawing on more than six hundred local histories from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island written between 1820 and 1880, as well as censuses, monuments, and accounts of historical pageants and commemorations, O’Brien explores how these narratives inculcated the myth of Indian extinction, a myth that has stubbornly remained in the American consciousness.

This description provides a constructive basis for individual historical societies in both the three states mentioned and elsewhere to examine how the Indian stories in their own communities have been dismissed, ignored or erased. That is consistent with my previously stated view that historical societies should tell the story of their land from Ice Age to Global Warming. The identification of the Indian history would seem to be a productive undertaking although I doubt most individual historical societies have the resources to do so or that there sufficient number of experts who can be consulted to help them.

VILLAGE ERASING ‘INDIAN’

Unfortunately, local historical societies may not have gotten the message that it is acceptable to investigate the Indian history in their own community. Here is one example.

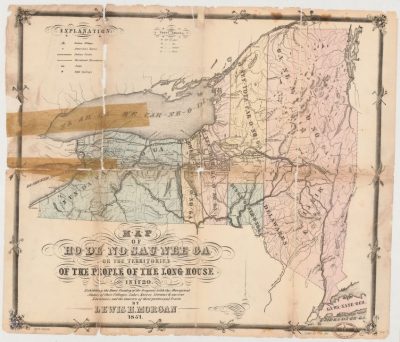

“Village Erasing ‘Indian’” was the front page headline of an article in The Freemans Journal, Cooperstown, New York. It seems that a Village trustee noticed the wording on a history marker at Council Rock, an Indian meeting place where the Susquehanna River flows out of Otsego Lake. The resident was shocked to see the text was: “Council Rock: Famous Meeting Place of the Indians.” The Trustee was aghast saying:

“I was shocked that I hadn’t noticed it previously. The sign refers to Native Americans as ‘Indians.’ It’s racially insensitive and incorrect, and it needs to be updated.”

That outrage sparked another Trustee to voice concern about another sign about the Indian Grave a few blocks from the meeting.

The first Trustee expressed concern about “this moment of social awareness and racial awareness” in the United States and called for contacting the New York State Department of Education responsible for state history markers. It was felt that the village needed to get out ahead of the “problem.”

A more intelligent Trustee commented that the “we shouldn’t assume what is politically correct or culturally correct. We need to do our due diligence.” This comment demonstrates the elevation of politically correct standards as the basis for rendering a decision. Think about that for a moment. A village government acknowledged that it was obligated to comply with politically correct standards even though Indians have expressed no objection to the term. The only issue for the village was the determination of what those standards was.

The reporter concluded the article with the droll comment that “The Indian Hunter” statue, the most famous statue in the village, was not mentioned during the deliberations.

As one might expect, the June 22, 2020, meeting led to a community response on the newspaper’s website. Here are some salient remarks.

1. One resident expressed the notion that to be truly sensitive to Native Americans meant returning the lands in Cooperstown taken from them. He suggested starting with the lakefront homes of one Trustee and the mother of a second Trustee.

2. One anonymous resident went to the NMAI website showing the information reported above. It noted the acceptability of the term “Indian” and the preference to call Indians by their tribal name.

3. A third resident responded to the oversight of not mentioning the Indian hunter statue. After all, hunting depicts Native Americans in a stereotypical appearance that could offend someone. [Apparently hunters are an offensive image to Indians. Indeed it is hard to image any culture anywhere at any time having a hunter as a hero.] This person went on to call for the removal of the statue of James Fenimore Cooper and changing the names of Fenimore Park, Fenimore Museum, and Cooperstown itself. After all, who knows what might be offensive to someone in the future. Ironically this article appeared in the local paper [yes, one still exists in Cooperstown] right next to right my blog Schuyler Owned People: Should Schuylerville Change Its Name? which the paper had published. This resident may have been speaking tongue-in-cheek as the comment ended: “Better to take it all down and change all the names. George Orwell would be proud.”

4. One resident was rather upset. “Who in the hell said ‘Indian’ is racist? No white person has that right? And it if was offensive, don’t you think it would have been changed years ago.”

The reference may also have to a previous village project which involved working with Mohawks and Oneidas where the issue of “Indian” hadn’t been raised.

The answer to the resident’s question about who determined the word Indian is racist would seem to be white people, not all white people, just some white people as this editorial states in discussing a related issue on the use of the term “Native American.”

Native American vs. American Indian: Political correctness dishonors traditional chiefs of old

This editorial by the Native Sun News Editorial Board (Sioux) in Rapid City, South Dakota began with that question and an answer.

Who decided for us that we should be called “Native Americans?”

It was the mainstream media of course….

The activist Russell Means preferred the name American Indian. He would say that just as you have Mexican Americans, African Americans, or Asian Americans, you should have American Indians….

During the activist days of the 1960s and 70s the U. S. Government responded to the activists’ protests by proposing the term “Native American.” And so the anti-government activists decided to accept the name Native American, a name suggested by the United States Government, a government that they despised. Say what?

That sad part of this entire fiasco is that so many of the so-called “elitist Indians” have allowed themselves to be bullied into using the name “Native Americans” and even “Native” by a white media that seems to have set the agenda for what we should be called. [The questions then to be asked is why did these white people did this and since whites are the dominant culture, what can Indians do to resist?]

One elderly Lakota man from the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation said recently, “If some Indians want to be called Native Americans or Natives, let them be called that, but I was born an Indian and I shall die an Indian. [This comment matches the words of Marc Lacey, the National editor of The New York Times: My father was born a Negro. Then he was black. Late in life, much to his discomfort, he became an African-American (John Lewis and “the Sad Demise and Eventual Extinction of the American Negro”: Erasing History).

So if you travel to any Indian reservation out west you will soon discover that nearly all of the indigenous people refer to themselves as “Indian,” especially the elders who are still fluent in their Indian language. As Chief Oliver Red Cloud said a few years before he died, “I am Lakota and I am Indian.”

As an Indian newspaper we must be very careful that what we call ourselves is not dictated to us by the white media. We have been Indians for a few hundred years and the name carries our history. Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull and Little Wound (Read their quotes) all called themselves “Indian” and they said it with pride. Should we dishonor them by saying they were wrong?

Political correctness be damned: We will use “Indian” if and when we choose. We will not be intimidated by the politically correct bunch or the white media.

The question raised by the teachers and the debate in Cooperstown suggest if Indians have not been intimidated by the politically correct, then non-Indians have. That still leaves open the question of the value added by using the term “Indigenous” instead of Indian.

To be continued.