This year for the first time I planned on attending the NCPH annual conference to be held in Atlanta, March 18-21. That conference along with many others has been cancelled due to the coronavirus. Instead of reporting then on what I observed at the conference, I will follow my custom of commenting on sessions based on online abstracts of presentations from conferences I did not attend but which I think are useful to the history community at large.

Opening Plenary // Present at the Creation: A Conversation with Pioneers of the Public History Movement

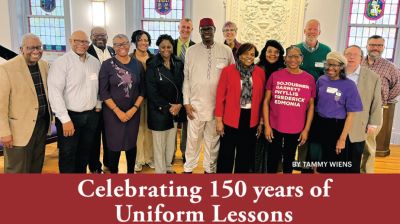

In 1979, an invited assembly of history professionals gathered in Montecito, California to explore the emerging field of public history. The energy of this Rockefeller Foundation-sponsored “History for the Public Benefit” symposium inspired a subsequent meeting at the National Archives in DC and organization of the National Council on Public History, which held its first conference in Pittsburgh the following year. In NCPH’s 40th year, this panel will discuss what transpired at early gatherings and the expectations that brought actors together. It will also reflect on the coalescing of diverse practitioners under the emerging public history field and NCPH banner at that time and reflect on the evolution of public history in the four decades since.

I intended to attend this session to familiarize myself with the organization. I note that people from NCPH including Marla Miller, the current president, are on my distribution list for this blog. My first contact with her was at a presentation at FDR Hyde Park in 2016 which I wrote about in The National Park Service Centennial: An Imperiled Promise. I ended up writing a series of blogs about that study which she co-authored and followed her career path with the NCPH.

One of the issues raised in the report related to the lack of opportunity for NPS history staff (and one could say for state historic site staff) to attend conferences such as this. Perhaps the message at least partially worked. One of the sessions I had hoped to attend was a NPS-based one.

Truthful Histories of a Complicated Past: Telling African American Stories through the National Park Service

Using a roundtable format, four scholars explore the implications of their work for the National Park Service (NPS) researching, analyzing, and interpreting African American histories and communities. Coming at their research from different professional backgrounds and NPS associations and looking at a variety of stories, each participant— bringing a unique practitioner point of view—will reflect with the audience on the challenges and opportunities the NPS encounters when highlighting traditionally underrepresented voices and histories. The conversation will explore the public implications of this work as well as the NPS’s collaboration with partners and the public.

Quite a few of the sessions, or at least the ones I had selected, involved slavery in one way or another. These sessions highlight what is being discussed, debated, fought over and provide a snapshot of where things stand at the moment. Rather than try to organize them, I will simply present them in the order in which they were scheduled to occur.

Implications of Monuments in Southern Communities

This session will focus on Southern commemorative landscapes and the debates surrounding monuments in these communities. In what ways do monuments evolve and change meaning as the years pass? In what ways do the meanings stay the same? Is there a good method to reinterpret problematic monuments while leaving them on the landscape, or is it imperative to remove them? Some examples of these new forms of reinterpretation will be highlighted in this session through digital and public art projects. In what way is the community involved in creating the collective memory of the country’s past? These questions and more will be addressed at this roundtable.

This session directly relates to my blog earlier this month on Do Monuments Matter: Race and Gender outside the Confederacy. The presenters were from South Carolina and Tennessee but the issue can be raised in the north as well.

Historically White Colleges and Universities Confront their Racial Pasts

Colleges and universities across America and particularly the South are increasingly confronting their racial, including slave-holding, pasts. This process can involve historical investigation, institutional bureaucracy, stakeholders with diverse backgrounds and interests, the voices of various publics and the implementation of acts of reconciliation. What commonalities have emerged among these institutions? What can we learn from each other? Are these undertakings and their outcomes a litmus test for an institution’s commitment to diversity and inclusion? How can this process illuminate other aspects of exclusion on our campuses? How can public historians bridge the various publics and contribute to the success of these efforts?

The presenters were from multiple states in the South. Again, colleges and universities in New England and the Mid-Atlantic have addressed these very same issues.

Weaving Generational Stories, Mending Wounds: Using Public History to Seek Healing and Justice between Jesuits and Descendants of their Enslaved

This roundtable and community viewpoints session will be hosted by the Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation (SHMR) Project, which researches and presents the lived experiences of individuals enslaved by the Jesuits and works with descendants and community stakeholders to establish healing processes. A panel of community stakeholders will engage discussions on shared authority, community engagement, and the role of public history in present-day activism in the context of how Jesuit slaveholding pertains to modern day injustices.

Since I did not attend the conference and was unfamiliar with this organization, I went to its website:

Historians have long known that the Society of Jesus relied on the labor of enslaved people. Enslaved people worked at Jesuit missions and schools in Alabama, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland and Missouri, as well as in Illinois, Kansas and Pennsylvania before they became free states. Their involuntary labor helped establish, expand, and sustain Jesuit missionary efforts and educational institutions in colonial North America and, over time, across the United States. This history is a source of shame for Jesuits today. We deeply regret Jesuits’ participation in this evil institution. No one today can reconcile these actions with the current teaching of the Church or with our commitments as Jesuits, but they are an undeniable part of our history. We are called now to an intentional response: one that foregrounds the lived experiences of the enslaved, acknowledges the legacies of Jesuit slaveholding, and is made in collaboration with descendants and those in our communities who continue to suffer from the consequences of slavery.

Reimagining Slavery and Public History: Charting New Directions in the Field

The edited volume Slavery and Public History: The Tough Stuff of American Memory (2006) remains a staple in public history classrooms and is often required reading for comprehensive exams, thesis development, and project background. Many of the essays provide important snapshots of the representation of slavery in public spaces during the 1990s and early 2000s. Since the book’s publication, however, much has changed, both in the field and in the national and global landscape. In this structured conversation, we invite our audience and panelists to reflect on the book’s legacy, identify its strengths and weaknesses, and thoughtfully question: what would an “updated” edition look like, and is one needed?

Obviously I do not know what was discussed or suggested at the conference. The description of the book is:

In recent years, the culture wars have included arguments about the way that slavery is taught and remembered in books, films, television programs, historical sites, and museums. In the first attempt to examine this phenomenon, Slavery and Public History looks at recent controversies surrounding the interpretation of slavery’s history in the public arena, with contributions by such noted historians as Ira Berlin, David W. Blight, and Gary B. Nash.

From the cancellation of the Library of Congress’s “Back of the Big House” slavery exhibit at the request of the institution’s African American employees, who found the visual images of slavery too distressing, to the public reaction to DNA findings confirming Thomas Jefferson’s relationship with his slave Sally Hemings, Slavery and Public History takes on contemporary reactions to the fundamental contradiction of American history—the existence of slavery in a country dedicated to freedom—and offers a bracing analysis of how people remember their past and how the lessons they draw from it influence American politics and culture today.

There is more to the conference than these sessions but I think this blog is already long enough. I will finish the review of the NCPH conference in the next blog.