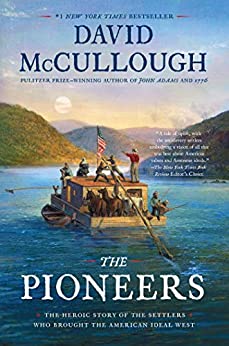

David McCullough and academic historians generally do not mix. Historians derisively refer to books by McCullough and his ilk as “airport books.” These are the kinds of books one buys in an airport and not at a history conference or from an academic press. Another derogatory term is (white) Father’s Day Gift.

Therefore it was a surprise to see a multi-authored section of the Journal of the Early Republic (JER 41 Summer 2021) dedicated to this author and this book. The editors announced it as a new feature called Critical Engagements. The section will appear from time to time in the journal. It will allow the history community represented by JER “to participate in conversations of great interests to scholars of the early American republic and the general public.”

For the first foray into this venture, the editors chose The New York Times #1 bestselling history book in 2019 herein called The Pioneers. The time period covered in the book directly coincides with the purview of the Society of Historians of the Early American Republic (SHEAR), the publishers of the journal. Its conferences have been the subject of previous posts here.

SHEAR CHAOS: A Culture Wars Train Wreck for a History Organization

August 19, 2020

Universities and the Legacy of Slavery (SHEAR Session)

September 22, 2016

Teaching Slavery: A SHEAR Perspective

September 12, 2016

“The Year without Summer” (1816): When Republicans Recognized Climate Change Existed (SHEAR CONFERENCE)

August 24, 2016

The General Public and the Early Republic Historians (SHEAR Conference)

August 23, 2016

In the session in this last blog, “THE PUBLIC AND THE EARLY REPUBLIC: A ROUNDTABLE ON IN AND BEYOND THE ACADEMY,” I wrote about the presentation by Connecticut State Historian Walt Woodward:

[He] gives about 75 public lectures per year. His experience has shown him that there is a tremendous public interest in Connecticut for history. He strongly advocates for historians to leave the ivory tower and venture out into the public arena. Walt generously provided some guidelines to be followed if you are so inclined [in my words].

Don’t speak academic or undergraduate-lecture style jargon to the general public.

Don’t assume prior knowledge (or that they read the assignment before the lecture).

Complexity is not clarity.

Nuance can be mind-numbing.

Park your biases at the door – leave out the progressive politics. You are there to share your presumed expertise in the past, not to indulge in being a know-it-all on a TV talk show.

Don’t be arrogant – you aren’t the god’s or goddess’s gift to humanity where the little people should bask in the aura of your greatness and be thankful that you have chosen to enlighten them.

The public audience loves history and wants to hear from people who knew it well and can communicate to them in an effective manner.

From the Q&A, I wrote: Walt is critical of the elimination (or reduction) of history in a STEM world. The history community is doing a poor job of communicating to the general public of history’s importance. There is a need to intervene in creating the k-12 curriculum.

In his session wrap-up, Commentator Peter Onuf, University of Virginia observed (in my words):

If students don’t care about history, then the professors need the skills of the public historian who has the job of reaching out to a general audience and then to apply those skills in the classroom to reach the students.

At least orally, Woodward seemed to be practicing some of the same techniques McCullough probably is in reaching out to the general public. Possibly public historians (I would include historians at state and national parks) do as well. How about academic historians?

The JER editors noted both the public attention and “stinging scholarly criticism” McCullough’s book received when it was first released. The objective of the editors in reviewing this book was clearly stated:

Given the reach of popular histories such as McCullough’s and the book and musical Hamilton, can we use such histories that reach and fascinate large audiences to show those hungry for exposure to the past how to think about history further and in new and more necessarily challenging ways? Can we as scholars engage with popular and less scholarly historical works beyond just pointing out their limitations? No matter how warranted or cathartic that reaction is, it often has the effect of alienating the public that enjoyed the book—not just from our critical reviews, but from our scholarship and even our methods and questions altogether. How can we reach that audience and build from the interest that propelled them to read McCullough’s book? How can our interventions offer a richer, more complicated picture?

Or, can we do what Woodward advised us to do at the SHEAR conference?

In this paragraph, the JER editors have expressed laudable goals as well as an awareness of the problem and perhaps the stakes. They are aware of the current controversies involving The New York Time Project 1619, another publication outside the academic arena. They are aware of the greater reach to the general public of these two non-academic and opposing publications. They also are aware of their own inability to reach out to the general public in a way that does not alienate or patronize them but instead serve as a necessary corrective. To some extent, this new feature represents a stab in addressing that need … subject to the fact that the audience for the section is the academic historians and not the general public who will never read this journal and probably not even aware of its existence.

Before delving into the reviews by five scholars on particular aspects of The Pioneers and the two scholars who reflected on the entire initiative, let me offer some thoughts about the approaches to the public taken by academic historians. Due to the length, this will require two blogs.

YOUR ANCESTOR IS A MONSTER

Genealogical research is a popular pastime in America. If you work in a library, archives, or museum (pre-COVID), then you are very familiar with people who are searching for information about their ancestors. They scroll through rolls of microfilm; the turn page after page of newspapers and other print sources; they search through databases. They are quite dedicated in the time they devote to the quest. They also are quite willing to share with others the results of their work. The work can be quite collaborative with multiple Facebook and other social media sharings.

And when they find something, truly it is a joyous moment. They may not quite run through the library in righteous exaltation with tears of happiness streaming down their face, but they are doing that mentally. Finding a never-before-known relative or a never-before-known action done by a known relative counts as blessing. Look what I found!

There are even “Hallmark-like” commercials dedicated to this phenomenon. A three-generation family may be seen wandering through giant displays of their ancestors’ lives. There are blowups of photographs and documents. Maybe a birth certificate. Maybe a census record. Maybe a naturalization notice. Whatever the image, there are the grandparents and parents proudly pointing to the next generation of the record documenting the life of an earlier generation, perhaps someone the child never knew personally but only heard about at family gatherings.

Rarely do you see someone jumping for joy to have learned that their ancestor was a monster. Given all the people searching for ancestors and all the ancestors there are in three, four, five, ten generations or more, someone at some point will come across someone they rather would not have as an ancestor. For example, there are people today who have learned that their ancestors owned other people. There also have been touching reunions based on that knowledge such as with the 1619 people.

Still people do not want to be told again and again that their ancestors were monsters. How many statues of Robert E. Lee does it take to cause a person to be stressed? How many times do you tell someone their ancestors were monsters before you have alienated them?

By these comments, I am not suggesting that academics in the public presentations (mainly virtual now) constantly berate and harangue their audience. After all it is not the ancestors of the members of the audience who have chosen to hear the academic speaker who are the monsters! But there are people based on race, location, and politics who well may be the descendants of monsters or be monsters themselves. And they do not need to be college graduates to understand that you are telling them their ancestors were monsters and they are too unless they repent their ancestors’ actions.

These considerations go the challenge of creating a national narrative for the 21st century. McCullough does it piecemeal through his books including about the American Revolution. For academic historians that effort is more problematic as will be discussed in the next blog on this initiative by JER: the message historians deliver on the legitimacy or illegitimacy of a country born in sin.